The date was February 1838. Action in the Upper Canadian rebellion had abated on Navy Island on the Niagara River and had temporarily ended in the Western District near the Detroit River. The theatre would soon shift to the Thousand Islands on the St. Lawrence River.

In his narrative of events, Patriot Robert Marsh, a resident of Niagara Falls, New York reflected upon the mood along the American/Canadian border at this time. He wrote; “It is all excitement in Buffalo, Cleveland, Detroit and all along the frontier...the whole country was awake; many and strong were the inducements for young as well as married men, to engage in so glorious a cause.”

This feeling was echoed in an article printed in the February 19, 1838 edition of the Albany Argus. It was reported that a considerable force of Patriots had gathered on the frontier in Jefferson County, New York. The article concluded by stating; “There begins to be some excitement here upon the subject of Canada. Many loads of men and provisions have been and are now passing here for the north.”

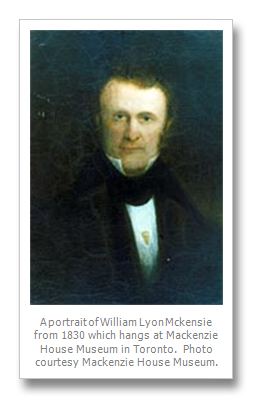

What had led up to this situation? Watertown resident Daniel Heustis provided some insight into this question. In his memoirs, Heustis who was a “captain” in the Patriot army, recorded that a meeting of Patriot leaders was held on January 16 in Batavia. William Lyon Mackenzie, Rensselaer Van Rensselaer, David Gibson, Bill Johnston and Heustis decided that a co-ordinated invasion of Upper Canada would be launched on February 22, Washington’s birthday. The rebel plan of attack was to be three-pronged. The main thrust would be made towards Gananoque, to draw loyal troops away from Kingston, prior to a full-scale incursion there. A second force would seize the provincial penitentiary to free prisoners, and a third group of sympathizers would attack Kingston and Fort Henry.

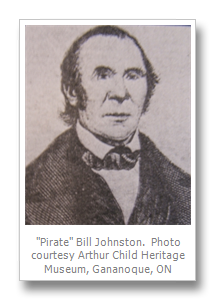

Several of the main conspirators moved to headquarters at the Mansion House in Watertown to further formulate these plans. There, a circular was issued and distributed throughout Jefferson County. It called for contributions of clothing and money. Concerted efforts were made to enlist men to the cause and to procure arms. Daniel Heustis personally travelled to Carthage, Champion, Rutland, Denmark and Lockport to collect more munitions. On February 17, the arsenal at Watertown was raided, netting the Patriot army 700 stand of rifles. These were transferred to French Creek (now Clayton) under direction of “Pirate” Bill Johnston. Several cannon belonging to artillery companies in surrounding towns were also “borrowed.” These were added to seven or eight already stored in Salina, along with arms pillaged from arsenals in Batavia and Elizabethtown.

Other Patriot supporters were actively engaged in collecting carriages, additional small arms and ammunition in communities between Champlain and Plattsburgh. Their avowed intention was the invasion of Canada at the first favourable opportunity. This initiative was confirmed in the February 21 edition of the Cayuga Patriot: ``We are informed by a respectable gentleman of Onondaga county, in whose statements the utmost reliance can be placed, and who has his information from undoubted authority, that the patriots had made their arrangements to attack Montreal, Kingston, Toronto and Malden.”

In an article in the Kingston Chronicle of February 21, intelligence reports were cited about men in Jefferson County drilling at night, the holding of private meetings and collecting money and provisions for the Patriots. In the following week’s edition of the Chronicle, a projection of what actually was to occur was printed: ``For some time past an attack upon Gananoque had been expected from the Sympathizers at French Creek.”

Articles in the Philadelphia Ledger & Daily Transcript explained more about the situation. In the February 27 edition the following update was printed: “We learn that the Patriots have finally made a movement. A large supply of arms and ammunition left Syracuse on Saturday evening for the lake shore, where a descent was to be made on Kinston.” In the March 1 issue, letters received on February 22 noted; “....the gathering of people at French Creek, Jefferson County, exclusively. We also learn that the number collected there was four or five thousand, and that they began to move at daylight that morning for Kingston”. It was also reported that several hundred men under arms night and day were expecting attacks at Prescott and Brockville.

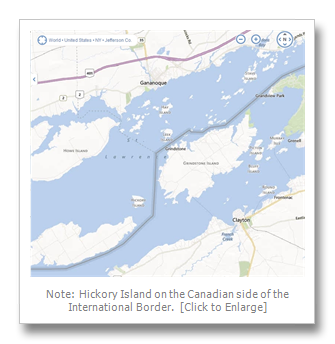

By the third week of February it was estimated that anywhere from between 1,500 to 3,000 Patriots were gathered on the south bank of the St. Lawrence River at French Creek. Daniel Heustis provided what probably was a reasonably accurate figure. He estimated that about 600 men had assembled with the intention of marching upon Kingston under the command of ``General” Van Rensselaer. On the evening of February 21, an advance party of 50 men moved from French Creek to Grindstone Island, and then crossed the frozen St. Lawrence to occupy Canadian owned Hickory Island. Located 25 kilometres east of Kingston and 8 kilometres south-west of Gananoque, Hickory Island was supposedly to become a staging ground for planned attacks on Gananoque and Kingston.

An article in the March 10 issue of Niles’ National Register noted that 4,000 stand of arms, 20 barrels of cartridges, 500 pikes and other provisions were transported to Hickory Island. It was unclear whether the timing of this incursion was actually part of the proposed co-ordinated assault on Canada, or made for another reason. Citing an undated excerpt from the Kingston Chronicle, the Register suggested that Patriot forces had moved to Hickory Island for fear of arrest by American authorities. It was even unclear what the ultimate aim of the invaders might be. An article in the March 1 issue of the Philadelphia Pennsylvanian which was excerpted from a letter to the editor of the Onondaga Standard, concluded that; “Their intended movement or point of attack is only conjectured. It is said to be Kingston by some: by others that their object is to make a stand on Canadian ground, to give confidence to the people in favor of revolution, and to adopt such plans as shall be thought advisable.”

On the morning of February 22, Daniel Heustis brought 50 more men to accompany those already assembled there with ``General” Van Rensselaer. These forces were joined later that day by a company lead by ``Captain” Lightie and additional Patriots from Syracuse headed by ``Colonel” Leman L. Leach (aka Lyman Lewis). ``Colonel” Martin Woodruff remained in French Creek to direct others to Hickory Island as new volunteers arrived. Throughout the day a large number of men in sleighs visited Hickory Island but they did not stay. During this period 110 men left taking 3 field pieces and most of the rebel stores with them.

Bill Johnston joined the group on the evening of February 22. Heustis pointed out that at no time did the Patriot force consist of more than 300 men. He had hoped for 1,000 volunteers and had had an ample supply of arms, ammunition and provisions for that number. He expressed his disappointment as the Patriot army continued to become “materially diminished.” “General” Van Renessalaer who was not sober, frittered away the day, dithered and made no clear decisions regarding future action. He watched his forces slip away in the bitterly cold -27 degree weather. As a result Patriot commanders “were obliged to pronounce the enterprise a failure.” Heustis volunteered to lead a group of men to attack Fort Wellington at Prescott. With diminished forces this plan was considered to be “too daring and impolitic” and therefore not feasible. The remaining Patriots withdrew to French Creek and disbanded.

Reaction on these events came from various quarters. William Lyon Mackenzie who had distanced himself from Van Renessalaer, felt that the attempt to join Patriots in arms in Upper Canada with refugees and American volunteers, was a promising opportunity to give republicans possession of Canada. In his Caroline Almanack, Mackenzie criticized the decision of the Patriots to appoint Van Renesselaer as leader of the Hickory Island expedition. He savagely concluded; “Let those who witnessed Mr. V.R.’s conduct speak of it - the golden moment has gone by, why should we say more?” An article in the February 28 issue of the Bytown Gazette poked further ridicule at Van Renesselaer and the Patriots: “The soi disant General deeming this force inadequate to the undertaking, (as well he might) gave up the attempt, and the rabble he had collected, by last accounts, were dispersing with greater celerity than they had assembled.” Van Rensselaer’s total unfitness to take charge of the Hickory Island incursion even came from a Patriot source. A perplexed Patriot “General” Donald McLeod wrote: “The expedition got up at Hickory Island by Col. Bill Johnson and Gen. Van Rensselaer....broke up, for some reasons not explained, without attempting any demonstration whatever.” McLeod concluded that the Hickory Island Patriots “had dispersed for want of a leader.”

The lack of volunteers responding to the call to attack Kingston was commented on in an excerpt from the Kingston Chronicle, published in the March 10 volume of the Niles’ National Register. It said; “This was a damper. The lookers-on bore the same portion to the actors as in other farces, and activity became the order of the day. The play was ended, and the audience retired.” Criticism was even expressed internationally. In the July 27, 1838 edition of the Hobart Town Courier an excerpt from an unnamed New York newspaper concluded that; “The expedition against Kingston....proved a miserable and ridiculous abortion. Timely notice was given to the authorities of Kingston by one of the United States’ marshals, and ample preparation was made to receive the invaders; but they took good care to go no nearer than Hickory Island, one of the ‘Thousand Islands,’ in the St. Lawrence, where they stayed shivering some 12 hours, and then straggled back and dispersed.”

_2.png)

Canadian officials had been made aware of the impending invasion. Brevet Major Richard Bonnycastle, de facto commander at Fort Henry, had sent agents to New York State to spy on the Patriots. This information was supplemented with additional details provided by Gananoque school teacher Elizabeth Barnett. She had overheard Patriot plans while visiting relatives in Lafargeville, New York. Bonnycastle sprang into action. He called up militia units from along Lake Ontario and the St. Lawrence River, and sent Major Thomas Fitzgerald with 200 men and 3 pieces of artillery to defend Gananoque. In the early morning of February 23, cavalry, infantry, artillery and militia units sent by Bonnycastle arrived at Hickory Island. This force under the command of the Honourable John Elmsley arrested five American farmers. John Packard, George Holsonburgh, John Martin, Ebeneezer B. Stores and John Herman were then taken to Fort Henry as prisoners of war. The only other remnant of the Patriot forces found was a large quantity of scrap iron sewn up in bags, intended to be used by the rebel artillery in place of grape shot or canister. The Bytown Gazette in its February 28 issue commented on what had occurred: “The inhabitants on the frontier had been thrown into a considerable degree of alarm, from an attack said to be mediated by the rebels combined with a set of marauders from the United States.”

The first action of the 1838 Upper Canadian Rebellion in the Thousand Islands/ St. Lawrence River had been inglorious and a complete failure for the Patriot army. The August 30 edition of the Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser reprinted a Canadian observer’s thoughts on these events. He reflected upon the situation and what was expected in the future: “Although the several attempts to invade us by the Americans have failed, and the schemes of the rebels in our own country are frustrated, we have still much to fear, as it is now evident that we have many amongst us who are yet ripe for rebellion. The large portion of the inhabitants, however, are loyal. The Americans may continue to sympathise with the Patriots, as they are called; they may raise armies too, of adventurers, headed by desperadoes, but unless they show more courage than they have in their late attempts to invade us, we have nothing to fear from that quarter.”

Only time would tell whether these prognostications would prove to be accurate!

By Dr. John C. Carter, drjohncarter@bell.net

Dr. John C. Carter is an Ontario historian, museologist and a Research Associate at the History and Classics Programme, School of Humanities, University of Tasmania. This is his fourth article written for TI Life (Click here view his other articles).

In addition Dr. Carter has provided a bibliography to study this important era of Thousand Islands history, which can be found un THE PLACE, History page.

More Suggested Reading:

“An Unsung Heroine,” Montreal Gazette (February 26, 1934)

Charles D. Anderson, Bluebloods & Red Necks (Burnstown: General Store Publishing House, 1996)

Richard H. Bonnycastle, Canada, As It Was, And May Be (London: Colburn & Co., 1852), v. 1

Ethel Comins, “Hickory Island Fiasco,” Bulletin of the Jefferson County Historical Society (October, 1966), v. 7, #4

‘‘Extract of a letter from a Gentleman attached to the Royal Army, dated Gananoque, Upper Canada, Feb. 28,” Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (August 30, 1838)

Robert W. Garcia, ‘‘This Period of Desperate Enterprise: British efforts to secure Kingston from rebellion in the winter of 1837-1838,” Ontario History (Autumn, 2009), v. CI, #2

Daniel D. Heustis, Narrative of the Adventures and Sufferings of Captain Daniel Heustis (Boston: Redding, 1848)

Kim Lunman, “The Heroine of Hickory,” Island Life (Summer, 2011)

Robert Marsh, Seven Years of My Life, or a Narrative of Patriot Exile (Buffalo: Faxon & Stevens, 1847)

Shaun J. McLaughlin, The Patriot War Along the New York-Canada Border (Charleston: History Press, 2012)

Donald M’Leod, A Brief Review of the Settlement of Upper Canada (Cleveland: F.E. Penniman, 1841).

John Northman, ‘‘Elizabeth Barnett, the Heroine of Gananoque,” Watertown Daily Times (October 6, 1932)

Dr. John C. Carter is a Research Associate at the History and Classics Programme, School of Humanities, University of Tasmania. He can be contacted at drjohncarter@bell.net