Patriot Chronicles: The Destruction of the Sir Robert Peel and Its Aftermath

May 29, 1838. It was a stormy night along the St. Lawrence River and in the Thousand Islands. The weather however was not as foul as the dastardly deed that was about to unfold. This event which Canadian historian Edwin Guillet has called “probably the most outrageous of all Patriot activities along the frontier,” became the next episode in the Patriot War.

The steamer Sir Robert Peel was built in Brockville by W. Parkin for the Jones brothers and Mr. Bacon of Ogdensburgh, at a cost of 10,000 pounds. It was launched on May 5. 1837. The Peel was commanded by Captain John B. Armstrong. On the evening of May 29, the vessel was on its regular trip from Brockville to Toronto. At about midnight it stopped at McDonnell’s Wharf, at Mullet Creek Bay, Well’s Island to replenish its supply of firewood. This was in American waters about 7 miles from French Creek in the St. Lawrence River. During a two hour stop over, Captain Armstrong was informed that a long-boat filled with men had been seen running past the island on two or three occasions. He took no heed of this warning, and the wood re-supply continued.

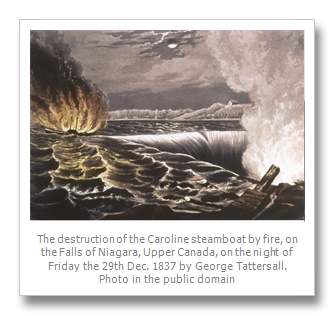

The observation however had been accurate. Two groups of Patriots lead by Bill Johnston and Donald McLeod had shadowed the Peel prior to its docking. These rowboats landed downstream and 28 men moved through the forest with the objective of capturing the Peel for use as a troop ship for Patriot forces. In addition, Johnston who would be later appointed as “Commodore” of the Patriot Navy, had been given instructions by the Canadian Refugee Relief Organization. He was to create a situation which would foster a spirit of war between the United States and Britain. William Lyon Mackenzie who was living in exile in Rochester, commented about this in the June 2, 1838 edition of his Mackenzie’s Gazette: “All is excitement here; and a rumour is afloat that the arrangements of the pirates were to make a simultaneous attack upon eight different boats at different places.”

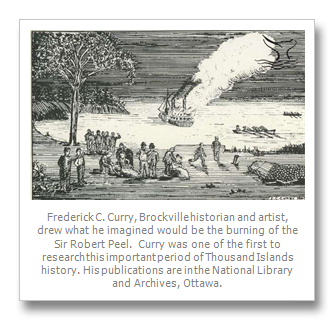

Some thought the planned assault on the Peel was the result of a grudge by the Patriots against Captain Armstrong, whom they believed to be a spy. Others viewed the attack as being an act committed in the spirit of revenge for the destruction of the Caroline, or in retaliation of Judge Jones’ harsh treatment of Patriot prisoners. William Lyon Mackenzie recorded in his 1840 Caroline Almanack that the Peel was owned by “...Judge Jones of Brockville and other tories, the Capt. of whom, Armstrong, was a spiteful loyalist.” Mackenzie surmised that the actions of Johnston and his gang were to be regarded as “some retaliation for the Caroline massacre.”

In other quarters, a more sinister motive for the attack was suggested: to make profit through robbery! Richard Bonnycastle, commandant of Fort Henry, echoed such feelings, calling Johnston “a disgusting brute.” Bonnycastle added that; “He [Johnston] was a coward as well as a pirate, and his whole course, magnified by a lying press on the frontier, would disagree the veriest jail-bird that ever flung his shoes in the air when turned off at Newgate.” Another loyalist, Colonel John Prince, made similar observations in the June 12, 1838 [Sandwich] Western Herald. Prince concluded that; “...the burning of the Sir Robert Peel Steamer, by a band of masked villains – [was] outdoing the worst deeds of the worst of the Pirates and Bucaniers of by-gone days.”

The Patriot forces continued to move towards the intended target. Unfamiliar with the surroundings, a number of the raiders became lost in the darkness. This left only 13 to take part in the actual attack. At approximately 2 a.m. on the morning of May 30, these armed men dressed and painted as Indians, came out of the bush. Shouting “Revenge for the Caroline,” they took control of the Sir Robert Peel from Captain Armstrong and his crew. The scene was described by a contemporary observer: “At this time great alarm was created among the ladies in consequence of the ruffians dashing their bayonets and lances through the cabin windows and breaking open various doors. At first those gentlemen who attempted to get out of the cabin on deck were pushed back, either by a slight push of a bayonet or by a strong one with the butt end of guns. The next order was for all passengers and hands to be put on shore; they at the same time shouted if they would go ashore quietly no one would be hurt. As all the passengers were in bed at the time many of them rushed on deck nearly naked, and were not allowed to return for either their clothes or trunks, but rudely pushed on shore if they did not walk off at once. There were only two cases in which they allowed those who came on deck to return for their clothes, but those who brought their clothes or trunks on deck were allowed to take them away. Several of the ladies were driven on shore in their night dresses, and the Ladies Maid told me they were not even allowed to take their jewellery.”

With all passengers and crew put off the vessel, the Patriots let the Peel drift 50 rods down-stream and then dropped anchor. They remained aboard for another half hour to pillage anything valuable and portable. Unable to restart the boilers, the Patriots decided to scuttle the Peel. They set the steamer afire and left for their hideout on Abel’s Island in three small boats. They were accompanied by passenger Dr. Thomas Scott who had volunteered to go with the invaders to care for wounded Patriot Hugh Scanlon. Captain Armstrong borrowed a skiff and rowed to Gananoque to raise the alarm. There he procured a horse and galloped to Kingston to find assistance. The American steamer Oneida picked up the Peel’s passengers and delivered them to their destination.

Word of the attack on and the destruction of the Sir Robert Peel travelled quickly. New York Governor William L. Marcy was informed about the affair by an express sent by Watertown District Attorney George C. Sherman. This information was provided by H. Davis, the Custom-house officer at French Creek. Governor Marcy started immediately for Watertown by stage coach and horse and arrived there within 50 hours. Marcy spent 10 days in the area gathering information about the incident. On June 4 he issued a proclamation offering rewards for the capture of the ringleaders: William Johnston $500, Donald McLeod $250, Samuel C. Fry $250, Robert Smith $250, and $100 per individual for all others involved and not yet arrested.

U.S. Deputy Marshal Jason Fairbanks ordered the militia to be called out to French Creek if necessary, to protect the town from expected British retaliation. Visions of war were entertained on both sides, and the Canadian government demanded the immediate punishment of the participating brigands. President Martin Van Buren was anxious that the matter not escalate into war with Great Britain. He dispatched Alexander Macomb, the senior general of the United States Army to take immediate measures to reduce tension and to enforce provisions of the Neutrality Act. Macomb’s orders sent to him from the American Secretary of War, Joel R. Poinsett, were straight forward: “Desirous of adopting every measure in the power of the Government to maintain the treaty stipulations existing between the United States and Great Britain, and to restrain our own citizens, and others within our jurisdiction from committing outrages upon the persons and property of the subjects of Her Britannic majesty, The President has, instructed me to direct you to proceed, without unnecessary delay, to the frontier of Canada, and to take command there.” As a result, the Eighth Infantry Regiment was created to serve on that northern frontier. It was stationed at Sackets Harbor under the command of Colonel William J. Worth.

Not to be outdone, the newly arrived Canadian Governor General, Lord Durham, offered a reward of 1,000 pounds for the apprehension and bringing before an U.S. tribunal, any person associated with the burning of the Peel. As the Peel had been destroyed in American waters, Lord Durham’s action elicited the following question from William Lyon Mackenzie: “Cannot the U.S. administer justice without British interference, offering blood money for offences done in their territories?” Durham’s announcement was a follow-up to a proclamation issued on May 31 by Upper Canada’s Lieutenant Governor, Sir George Arthur in which he urged Canadians not to retaliate. Lord Durham also added assurances that initiatives would be taken to protect the civil population of Upper Canada and to defend Canadian territory. In further decisive action, Durham sent his brother-in-law Charles Grey, as his personal representative to Washington. Grey’s task was to diplomatically request that the American government assume its share of blame, and that American executive power be used to protect the safety and rights of citizens of both nations.

In an ironic twist of fate and quite opposite to the intentions of the Patriots, Canadian novelist Major John Richardson suggested that the attack on the Peel had in fact assisted Durham in “the attainment of a full and satisfactory understanding with the American government.” The outcome of Charles Grey’s mission was that he received assurance from President Van Buren that “...not only the strictest neutrality should be preserved, but that competent and experienced officers should be dispatched to the frontier with a view of its enforcement.” Another outcome after the attack on the Peel was Sir John Colborne’s order that Prescott’s Fort Wellington be repaired and that a new blockhouse for 100 men be constructed. This work commenced in the late summer of 1838 and was completed in February 1839.

Reaction in the press was also immediate. An editorial in the May 30 issue of the Oswego Commercial Herald concluded that; “This daring piracy excites a just indignation among all classes, and calls for the vigilant and energetic action of the public authorities to detect and punish the perpetrators.” Diligent American response resulted in the arrest of 7 men at Depauville, New York and eventually the incarceration of 12 participants in the Watertown jail. They were indicted not for neutrality violations but for arson in the first, second and third degree. Skepticism about the outcome of the trials for those arrested was voiced in the June 6, 1838 edition of the Kingston Chronicle & Gazette: “We entertain very little doubt that they also will be acquitted. If [Hugh] Scanlan and the redoubted Bill Johnston, with their followers do not escape the gallows or the penitentiary, we shall be very much astonished.”

William Anderson was the first to be tried. His trial commenced on June 23, 1838. District Attorney for Jefferson County, George C. Sherman, Bishop Perkins, long time District Attorney for St. Lawrence County and Samuel Beardsley, the Attorney General for New York State conducted the prosecution. Anderson was defended by lawyers Calvin Mc Night, Benjamin Wright, John Clarke and Bernard Bagley. After two hours of deliberation the jury brought in a verdict of not guilty. The trial for the other defendants was set for November 18, 1838.

Bill Johnston had not been captured. In a June 10 letter to the editor of the Watertown Jeffersonian, Johnston confirmed that he had commanded the expedition which had attacked and destroyed the Sir Robert Peel. He assured readers that; “The object of my movements is the Independence of the Canadas. I am not at war with the commerce or property of citizens of United States.” Further information contained in a July 18 article in the New York Morning Herald (reprinted in the Hobart Town Courier of December 7, 1838), concluded that; “He [Johnston] considers the destruction of that vessel as an act of piracy, and that his life has become thereby forfeited, and he says he shall sell it at the dearest rate.”

Focus shifted to efforts to capture Bill Johnston. An article in the Hobart Town Courier noted that the destruction of the Sir Robert Peel “...was an act of a set of scoundrels who have taken up their abode in one of the cluster called ‘The Thousand Islands’...they are under command of a notorious bandit, familiarly known by the name of ‘Bill Johnson,’ a sort of fresh water Paul Jones.” First Lieutenant Charles Allan Parker of the Royal Marines, recorded in his diary that the hunt for Johnston commenced with the fitting up of a flotilla of schooners and gunboats assembled to accelerate his capture. On June 29, Parker accompanied Captain Williams Sandom aboard the steamer Experiment to where the Peel had been burned. They were joined by a guard of 30 men to meet American authorities aboard the steamer Telegraph. Parker recalled the result of this meeting: “It ended in a Mutual agreement that in the chase after the notorious pirate Bill Johnstone, that either party should freely land on the islands of the other, but should not on the Mainland.” The details of this arrangement were printed in the Sydney Herald. It extracted news from the Sackets Harbor Whig which said that by mid July, “...the British authorities, availing themselves of so extraordinary a license, commenced scouring the Islands and shores of the St. Lawrence with a large body of regular British soldiers.” American Colonel William J. Worth co-operated with the British Army stationed at Kingston to initiate joint patrols. The Sydney Herald confirmed that a combination of English and American forces worked together in efforts to capture Johnston. This culminated in a surprise raid on the house of John Farrrow on Grindstone Island. On July 11, 1838, a party of 80 men under the command of Captain Gwynn of the U.S. First Regiment of Infantry, along with a force of British soldiers all aboard the Telegraph, captured 2 men. However Bill Johnston and 5 other confederates escaped.

The trial for the remaining Patriots arrested for their involvement in the Peel affair and still held in the Watertown jail, was to begin on November 18. Ironically this happened to coincide with the Battle of the Windmill, and prosecutor George C. Sherman could not get necessary witnesses from Canada to testify. In a reprint from the Watertown Jeffersonian, the Onondaga Standard of December 26, 1838 explained this situation: “The disturbed state of the frontier, it is presumed, is the cause for the non attendance on the part of the Canadians who were expected to bear testimony against the prisoners. It is proper to remark that the prisoners were discharged from confinement.” Without witnesses, Judge Gridley released the prisoners on their own recognizance, and no further indictments were moved against them.

Memories of this episode in the Patriot War began to fade. The destruction of the Sir Robert Peel became a footnote in the maritime history of the St. Lawrence and the Great Lakes. It was listed and recorded for posterity in the January 1845 issue of Simmond’s Colonial Magazine: “Sir Robert Peel Destroyed by the Patriots in 1838.”

Tangible evidence of this event in the Patriot War can be found in a song probably composed by one of the men in Johnston’s boarding party and the Thousand Islands Museum in Clayton, NY has a framed apron on its walls. Next time you are in the region, be sure to stop in and see this unique piece of history.

The “Sir Robert Peel”*

In the pleasant month of May, ‘twas the year thirty-eight, At the close of the month, one night very late, It was down in the narrows where they watched for the eel Lay Her Majesty’s steamer called the Sir Robert Peel.

It happened by chance, or so ‘twas understood, That the steamer was forced to call there for wood. At her prow from three rowboats so nimble of heel Sprang a band of bold fellows aboard of the keel.

They says to her captain, likewise to her crew: “Remember the Caroline, and remember Cap Drew, So pack up your baggage for now we do feel Quite fully determined to burn down the Peel.”

They cut loose her fastenings and out in the stream They cast both her anchors and blew off the steam. They put in the fire and she burnt to the keel Crying, “Our wrongs are avenged by the burning of the Peel.”

Hurrah for Bill Johnston, hurrah for his braves! Just give him some seamen, and we’ll never be slaves. If you rob him of wealth and you arm him with steel, Then the fate of the Tories can be read in the Peel.

Now liberty rises and puts forth her power: ye tyrants she seizes and points to the hour. Ye tyrants from Europe our vengeance shall feel Unless you are warned by the burning of the Peel.

Unknown

|

A Reminder of the Patriot War

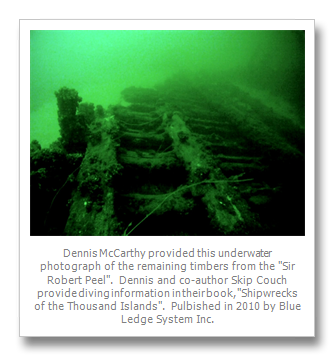

Dennis and Kathi McCarthy, provided these photographs and information:

This apron was worn by a passenger of the steamer “Sir Robert Peel.” … Johnston made no attempt to conceal his part in the affair. He boldly caused a proclamation to be published in the newspapers stating that he commanded the expedition.

The apron was dropped by one of the women passengers when she left the boat. It is presumed that Johnson picked it up as it soon came into the possession of his wife. she later gave the apron to Juliana Hawes, sister of Charles Hawes who married Bill Johnson’s daughter Kate.

Juliana Hawes married Captain Archie Marshall, one of the best known of the old time lake Captains. When she died at 98 years old, the apron went to her granddaughter, Mrs. Marie Marshall of Clayton who donated the apron to the T.I. Museum.

Thousand Islands Museum, 312 James St., Clayton, NY 13624

www.timuseum.org |

By Dr. John C. Carter, drjohncarter@bell.net

Dr. John C. Carter is an Ontario historian, museologist and a Research Associate at the History and Classics Programme, School of Humanities, University of Tasmania. This is his fifth article written for TI Life (Click here view his other articles). In particular his February 2013 Patriot Chronicles: The Hickory Island Incursion.

In addition Dr. Carter has provided a bibliography to study this important era of Thousand Islands history which can be found in THE PLACE, History page.

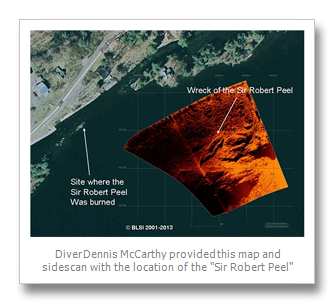

Supplemental information was generously provided by Dennis and Kathi McCarthy, Blue Ledge System Inc., Cape Vincent.