Before we had hotels, we had inns. Before we had inns, we had taverns. The earliest accommodations for visitors on the river were taverns. At Alexandria Bay, Charles Crossmon took over his father-in-law's rustic tavern in 1848. A "tavern" was was a public house, licensed to sell alcoholic beverages, which might have some sleeping rooms attached. An inn, in contrast, was more geared to accommodating travelers, but would have a tavern's "tap room" attached. Crossmon's tavern became an inn, then finally a rather grand hotel.

Less well remembered than Alexandria Bay's early tavern was Clayton's Hubbard House, which also grew to become a large hotel before it likewise disappeared.

The first Clayton tavern appeared before 1820. The proprietor's name is forgotten. Probably it was not so much a proper "inn" as was the Hubbard House. When was the Hubbard House built? The architectural style is Greek Revival, generally representing the second quarter of the nineteenth century. The building may have been constructed by Capt. James T. Hubbard, who was decades later recalled as starting hotel keeping in 1857. Hubbard might have acquired an earlier building, or might have built his inn in an old-fashioned style.

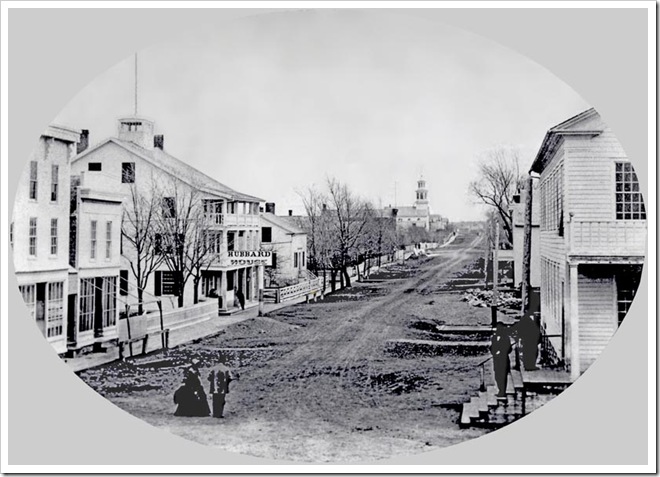

Capt. Jim Hubbard's early hostelry was a proper inn, not merely a tavern. Two distinctive building types accommodated the two facilities. A tavern was really a typical house where guests were welcomed, whereas an inn was designed differently. The wood-frame building type is found from coast to coast, known as a "settlement hotel," probably because it was one of the first buildings to be constructed in new settlements on the frontier. Such an inn is not merely larger than a tavern; it had a visual identity that informed travelers that it offered hospitality. Usually it differed from most buildings by turning its broad side to the street, with gables on the side walls. Then, even more distinctively, it had long porches on the street side, sometimes only one story, but more typically two stories, or even three, as we see at the Hubbard House:

Clayton's James Street, Hubbard House with three stories of porches, left.

Porches were were not common on houses of the early twentieth century, but became fashionable only in the second half of the century. The earlier inns probably featured porches for functional reasons: rooms usually held multiple occupants (sometimes several sharing a bed) so could become warm and otherwise unpleasant during the summer. Porches on all levels allowed guests not merely to escape to a rocking chair in the fresh air, but even to sleep outdoors. We may find it difficult to imagine the conditions endured by travelers in the early nineteenth century. One of them complained, "After you have been sometime in bed, a stranger of any condition (for there is little distinction) comes into the room, pulls off his clothes, and places himself, without ceremony, between your sheets." Taverns and inns were very democratic.

There is little social pretension in early hostelries. They were rowdy, noisy places. One guest noted in his diary that others were drunk and staggering, and "kept up the Roar-Rororum till morning." One slept lightly, if at all, and "watched carefully all night, to keep them from falling over and spewing upon me."

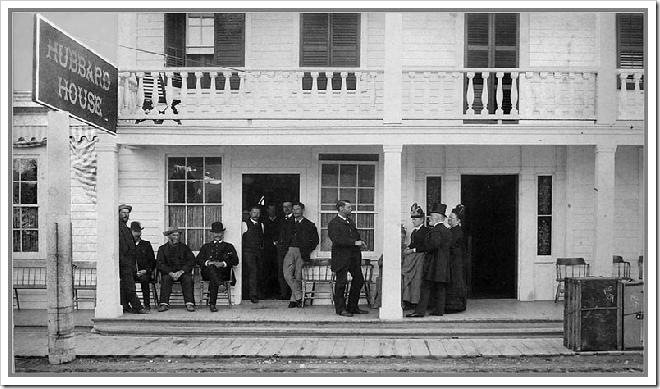

The early fishermen who returned to Charles Crossmon's tavern summer after summer probably accepted the poor beds and bed bugs usual for taverns as "roughing it" for their sport. But when the railroad provided more comfortable and rapid access to the river, wives and children began to accompany the fishermen. Probably "Genial Jim" Hubbard catered to a more refined clientele from the outset, as suggested by the wonderful early photograph of the host, guests, and locals on the porch of his inn:

Capt. Jim Hubbard, center, chats with fashionable guests outside the main entrance to his inn, right. Their trunks stand at extreme right. Others, probably guests, stand in the door to the tap room. Some of the gents seated at left may be "oarsmen" (fishing guides) awaiting customers.

The porch was the signature icon of the early American inn, especially important to a summer resort facility like the Hubbard House. The porch (or "piazza" or "veranda," as known at the time) mediated between indoors and outdoors, between the public zone of the street and the interior realm of the house. On the porch a row of chairs and benches welcomed local residents as well as visitors, encouraging interaction. Here fishing guides would dispense tales and await customers. Porches on upper levels were less public, favored by ladies for whom sitting on the sidewalk seemed inappropriate.

Interior layout of this sort of inn was fairly standardized. The main door, with sidelights, would open into a wide center hall with stairway along one wall (probably the right side). A door to the left would open into the tap room, while one on the right led to a parlor. The tap room of these early taverns had a bar within a wood-slatted enclosure, which would secure the rows of bottles after hours. Bar sales have always been a major source of hotel revenue. A convivial bartender was a great asset, attracting locals as well as travelers to the tab room. Across the hall, the parlor was the "withdrawing" room for ladies, who would avoid the smoke and foul language of the tap room. Food would be served in both places, on the "American plan," with cost of meals included in the bill for lodging. Both rooms had fireplaces, although cast-iron stoves were more used at the time (except in bed rooms, which were unheated). On the main floor, opening off the center hall at the back would be two more rooms, one a kitchen and the other a dining room. When the dining bell rang, all ate at one or more large tables here, if not served in the tap room or parlor. The host and family might join guests at table, if not otherwise occupied or eating in the kitchen. The Hubbard House was famed for it's Sunday dinners.

Early taverns and inns were usually family homes, opened to guests. The owner was not merely an absentee proprietor. He was more literally "host" to his guests, more personally concerned (despite the relatively crude facilities) with their welfare than today's usual hotel manager, who may never meet his guests. The proprietor of the early inn behaved not like a desk clerk or head waiter but more like the owner of the large house, entertaining guests. "Genial Jim" sat at the head of the guest/family table, carved the meat, and kept conversation lively. Similarly, Eleanor M. Hubbard, like most hosts' wives, was a public presence, not merely planning the menu and supervising the kitchen and dining service, but personally bringing large platters and bowls to serve family-style. In the last years of the Hubbard Hotel her successor, Mrs. Harold Bertrand, played the same role, presiding over a noted kitchen and dining room. The quality and quantity of food was important to popularity of the house. Many guests were return visitors, many of them brought to Clayton by the noted fishing. Eleanor Hubbard packed lunches for guides' shore dinners prepared on some island. Guests sitting in the Hubbard House parlor no doubt felt that they were in Mrs. Hubbard's home parlor--that Eleanor was indeed their personal hostess. Eleanor M. Hubbard became proprietor of the much larger hotel in the 1890s, after Capt. Jim died. She was still packing lunches for fishing parties at the end of the century, after forty years.

In time, the Hubbard's inn, no longer their personal home, became a full hotel, although still called the Hubbard House. A brick structure (built in two stages) supplanted the wooden inn. A large dining hall with smaller tables replaced the the long ones in the smaller dining room. If some of the communal intimacy was lost, American hotels remained famous for conviviality. One was expected to participate in lively conversation with strangers. Not to participate was considered an affront to democracy, "a species of neglect, if not offense. . . . You may sin and be wicked in many ways, and in the tolerant circle of American society receive a full and generous pardon. But this one sin can never be pardoned." Like Charles Crossmon's institution at the Bay, Capt. Jim became a host favored by celebrities and an affluent clientele. The Hubbard House was noted as the venue for New York City theatrical folks.

The site of the Hubbard House on Clayton's James Street is now a parking lot, ringed with motel accommodations. Probably the original inn could be recreated within the open parking area without disrupting the motel facility. Given the increasingly upscale boutique character of the opposite side of James Street, a recreated historic inn across from them would be far more appropriate than the present lot, usually largely empty except for a scattering of parked cars. Clayton has few historic buildings of this pre-Civil War vintage. A reconstructed inn here would be a landmark centerpiece of the shopping district, an iconic attraction for the village.

Hotel: An American History, the new book by A. K. Sandoval-Strausz, provides excellent description of hotel types and their operation. Yale University Press, 2007.

By Paul Malo