Cornelius Cook is buried in the Cross Cemetery, only a few kilometers north of the River and the site of his lightkeeping work. Nearby are buried two others who acted as lightkeeper for the Gananoque Narrows and Jackstraw Shoal lighthouses.

Located in an intricate part of the Thousand Islands, approximately three kilometers apart, these two lights effectively functioned as a pair. The Gananoque Narrows Light was located on the east end of Prince Regent (or Little Stave) Island. Jackstraw Shoal Light was erected on a pier, on the north side of the channel, three miles below Gananoque. A single keeper was assigned to watch them both, from the time of construction until they became unwatched lights. In 1856, Cornelius Cook was appointed the first of those lightkeepers. The Cooks and the Crosses were local families, and we see both family names as lightkeepers here. Cornelius married Sabra Ann Cross in 1843, linking the two families by marriage.

Cornelius Cook was lightkeeper for less than two years (1856-1857), receiving a salary of £22.s10 for each light. He was soon replaced by James McDonald, who acted as lightkeeper from 1857 until his death in 1867. During these years, the island became known locally as McDonald Island, a name that stayed in use for many years. Thus, we see Prince Regent shown as McDonald’s Island on the 1897 chart, and the lighthouse as the “MacDonald’s Island Light” in a souvenir booklet produced by the Marshall Bros. in 1912. Mr. McDonald and his family lived on nearby Sugar Island, as there was no lightkeeper’s dwelling yet provided. He was reported to have purchased both Sugar and Little Stave Islands, but this was disputed after his death.

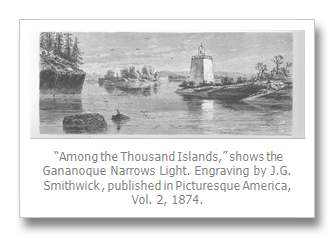

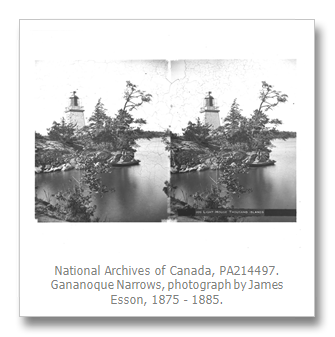

Images of the Gananoque Narrows Light are relatively common, in paintings and illustrations, photographs and postcards; it was the most commonly depicted lighthouse of those on the Canadian side of the Thousand Islands. Images of Jackstraw Shoal, in comparison, are difficult to find. It was a more isolated structure, on a pier in the River, and was far less popular with artists and photographers. One of the earliest images shows Gananoque Narrows in 1874.

After James McDonald’s death, Cornelius Cook returned as keeper, but this time he remained for 18 years (1867-1885). His salary was now paid in Canadian dollars: $395 annually for keeping the two lights. During Keeper Cook’s tenure, records speak of continued maintenance of the light towers, as well as the occasional upgrade. For example, between 1875 and 1878, a dwelling was built (on Prince Regent Island) for the lightkeeper’s accommodation, and in 1880, Jackstraw Shoal Light was moved 31 feet to the north of its original position, and its height raised three feet above its original level. For the most part, the lightkeepers lived a daily ritual of routine chores (spelled out in a detailed book of rules), but there were also moments of excitement from time to time. From the Gananoque Reporter newspaper of October 27, 1877:

“Edward Hunter, while sailing from Fisher’s Landing to Gananoque, was capsized and had a narrow escape from drowning. His boat sank, and he was left struggling in the water. Mr. Cook the light keeper, witnessed his plight and put out in a boat and rescued him.”

|

Tourism was gradually increasing in the Thousand Islands region, particularly following a visit to the Thousand Islands in 1872, by American President Ulysses S. Grant. Rail and steamboat were then the two main means by which visitors could travel, so the role of the lighthouses and their keepers, as aids to navigation, became increasingly important.

An 1874 report by the Superintendent of Lights says, of Gananoque Narrows and Jackstraw Shoal:

“Light-houses in good repair. Three base burner lamps in each. Keeper has no dwelling-house.”

|

A description in the 1878 Sessional Papers contains the first mention of a dwelling house, with its discussion of the keeper’s family:

“Mr. Cornelius Cook is the Keeper, he has four in family.”

“The light is placed on the north-east end of Little Stave Island, and is a white Square tower 44 feet high; the lantern is of iron, and contains three No 1 flat-wick lamps with three 15-inch reflectors, and is a fixed white light, catoptric; sized of glass 14 x 16 inches. Lantern is 6 feet 6 inches diameter.”

“The light is well kept.”

“Jack Straw Beacon, in connection with the light, requires to be rebuilt. Two mooring hooks are required; windows in dwelling to be refitted.”

|

Cornelius Cook purchased Stave Island in 1881, where he built a house and barn, and cleared many acres of land, which he farmed. After his death in 1885, Joshua Legge was appointed as lightkeeper, only to resign in 1887. He continued to reside in the area, however, and in 1892 was paid $425 to repair the piers at Jackstraw Shoal:

“30 cords of stone rip-rap supplied, the lighthouse elevated, and the sub-sills renewed; a new lantern deck laid, and other repairs made to the building, which was old and in bad order. This work was done under contract by Mr. Joshua Legge.”

|

By the late 1800s, more changes were occurring in the region. Many of the American islands had been sold to private individuals, and elaborate homes had sprung up. Development on the Canadian side was just beginning. Tourism was still increasing, and the era of the big resort was about to boom. The Victorian romance with the natural world was blossoming, as disillusion with the industrial revolution set in, and the idea grew that communion with Nature would be good for a person. People wanted to escape to Nature to heal, natural themes appeared on wall paper and in drawing rooms, the Arts and Crafts movement was beginning to flourish, and romantic poems such as “Geraldine: A Souvenir of the St. Lawrence” were published. An 1887 illustrated edition of this poem featured artwork by A.V.S. Anthony, with pictures that not only depicted themes in the poem, but actual sites and features along the River. The engraving of a lonely steamer passing the Gananoque Narrows Light shows the lightkeeper’s dwelling, as well as the lighthouse tower.

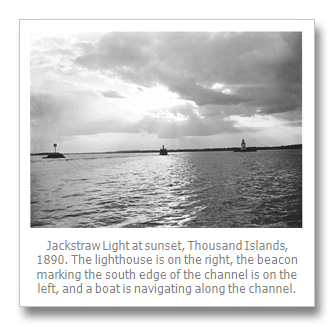

John H. Davis was appointed lightkeeper in 1888. At around this period, we see an early image of Jackstraw Shoal. In two photographs from 1890, one of each lighthouse, we can also see the paint job that was unique to these two lighthouses, with the four corner edges painted a dark color, probably red, contrasting the white walls of the frame towers. This appears to have been a color scheme adopted for a period at these two lighthouses only, for it is not seen in images of any other lighthouse in the Thousand Islands.

Sanford Davis took over as keeper of the lighthouses on July 26, 1892, upon the resignation of J.H. Davis. Sanford was likely a son of J.H. Davis, but no information has been found to confirm or refute this supposition. We do know, however, that the job of lightkeeper was passed from father to son, or from man to widow, among lightkeepers in general, and that we can see several other instances among the lightkeepers in the Thousand Islands specifically.

Another moment of excitement occurred on September 4, 1894, when a lamp exploded at the Gananoque Narrows lighthouse, damaging the lantern and the top part of the tower:

“The damage done by fire was repaired and advantage was taken of the occasion to remove the small panes of glass from the old-fashioned lantern and replace them by large panes of plate glass; at the same time a seventh order dioptric apparatus of Chance’s make was established at the light station instead of the lamps heretofore used.

“Advantage was taken of the presence of a skilled mechanic at Gananoque Narrows to replace the small old-fashioned glass in Jack Straw lantern by modern plate glass.”

|

Manley R. Cross (probably a nephew to Cornelius Cook) took over as lightkeeper of Gananoque Narrows and Jackstraw Shoal lighthouses in August of 1896.

The lighthouses had been fueled by coal oil since whale oil was phased out in 1860, but by 1903 a move was afoot to introduce acetylene as an alternative, with the intent of making the lighthouses “practically automatic.” Consequently, in 1904, the services of the lightkeepers at four of the other Thousand Islands lighthouses (Burnt Island, Red Horse Rock, Spectacle Shoal, and Lindoe Island) were dispensed with. Manley Cross then became the sole keeper of six lighthouses, at an annual salary of $480.00.

Most lightkeepers did work other than lightkeeping (often farming, like Cornelius Cook) to help support their families, as lightkeepers were among the lowest paid civil servants. Government records document recurring discussions around this issue. The low salaries sometimes made it difficult to keep qualified keepers, and many of those who did stay found supplementary income, although details are scarce. Manley Cross was hired by the American Canoe Association in 1904, to act as the first caretaker of their Sugar Island property. He was apparently responsible for watching over the site and undertaking general maintenance, and for welcoming visiting canoe enthusiasts during the summer months.

On December 7, 1907, however, the Gananoque Reporter newspaper announced:

“Mr. Manly [sic] Cross died at his residence, Halstead’s Bay, on Thursday morning

last, after an ilness [sic] of a nervous nature extending over several weeks. Deceased was between forty-five and fifty years of age [he was 45] and was born and always lived at Halstead’s Bay. . . . During his illness his son has been doing this work.”

|

Despite local expectation that this son (Milton Cross) would replace his father, it was Manley’s widow, Mrs. Manley (Jennett) Cross who was appointed as lightkeeper in January 1908. Born Jennett P. Elliott, Jennett Cross was the only woman to have acted as a long-serving lightkeeper in the Thousand Islands (on either side of the border). She was paid $550.00, later $600.00 per annum, as the government was forced to improve salaries when faced with the increasing difficulty of securing staff.

In 1908, women were not permitted to vote, and were not even considered to be “persons” in the eyes of Canadian law. Women won the right to vote in Ontario provincial elections in 1917, and in federal elections in 1918. When the Supreme Court of Canada decided, in 1927, that women were not “persons” (not one of their finer moments), the “Famous Five” took the matter to the Privy Council in England, who announced in 1929 that women were actually “persons” after all. It is ironic that this non-person, Jennett Cross, had sole charge of six of the lighthouses in the Thousand Islands.

In May 1912, however, the government reverted to coal oil as the fuel at the Thousand Islands lighthouses, “for reasons best known to themselves,” as the Gananoque Reporter put it, resulting in the recall of the dismissed lightkeepers. Mrs. Cross continued to act as lightkeeper for the lighthouses at Gananoque Narrows and Jackstraw Shoal for another two years, however, retiring after six years as a lightkeeper.

Thomas (known locally as “Poppy”) Glover, appointed on February 3, 1914, would be the last lightkeeper at these two lighthouses and would also be the longest serving. He lived in the keeper’s dwelling on Prince Regent Island, and for some years ran a small library out of the building, for the use of island residents.

During the 1920s and 1930s, the number of lightkeepers across Canada dwindled. Details of government expenditures include monies for “removing lighthouse keepers,” as automation, spread. The general approach was to move to automation upon the retirement of the keeper, and when Thomas Glover retired in 1937, Gananoque Narrows and Jackstraw Shoal lighthouses became unwatched, leaving only three lightkeepers in the (Canadian) Thousand Islands. At this point, significant structural work was done on the lighthouses, to suit them for their new automatic role. Gananoque Narrows and Jackstraw Shoal became unwatched lights in 1937, and were designated as such in the annual Lists of Lights from that year forward. The lights were not totally unwatched, however, as caretakers were appointed at some lighthouses. Caretakers would have duties related to checking the lighthouses for structural or other problems, but would not have the same residential requirements as a lightkeeper. Unfortunately, the government records are silent about these workers. Some area residents recall the “lightkeeper” Sam Liddell, who acted as a caretaker of these lighthouses for a number of years after their automation.

Further information gleaned from Lists of Lights indicate another major rebuilding effort in 1946, which was likely a conversion to electricity (known to have occurred the same year at Burnt Island, Spectacle Shoal and Red Horse Rock, when Lightkeeper Ferris retired), and another to Jackstraw in 1955.

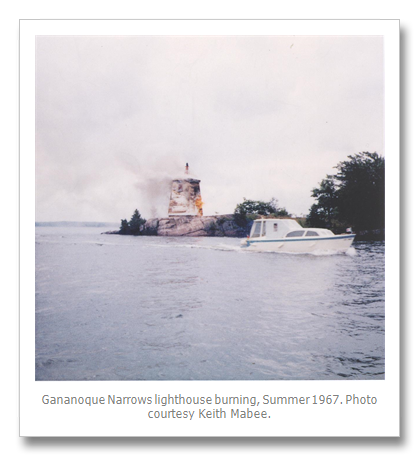

It is not certain how the original Jackstraw Shoal light tower met its demise, but it was described as a “circular white concrete tower” in the 1962 List of Lights. The old wooden light tower was likely torn down and replaced some time in 1961, due to the constant maintenance demands of that location. The Gananoque Narrows lighthouse tower lasted only a few more years, before being destroyed by fire in 1967. Many river residents can recall that day, and Keith and Metje Mabee have the photographs they took. Some area residents suspected the Coast Guard of ridding themselves of a structure that was falling into decay, but Coast Guard staff were told that a lightning strike, or possibly vandalism, was responsible for the fire. The government of the day certainly had no concept that the structure might have any historic or other value, however, as the Coast Guard actively tore down several of the other old, neglected wooden lighthouse towers that same summer, “beautifying the river” for Canada’s centennial celebrations.

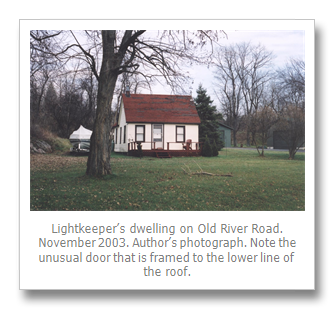

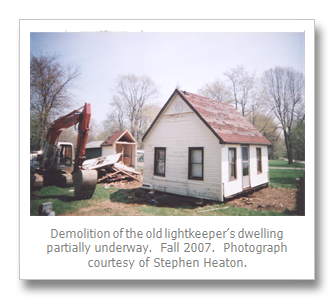

The lightkeeper’s dwelling lasted much longer. It was hauled across the ice one winter in the 1940s, and stood for many years on a lot along River Road, where it was used as a cottage. Sadly, new owners tore down the aging structure in early 2007, to make way for redevelopment. It was another missed opportunity for heritage protection, as there had been some efforts to recognize the historic value of the building.

By Mary Alice Snetsinger, ecoserv@kos.net

Mary Alice Snetsinger is a conservation biologist now working in Kingston. She grew up in the United States and Canada, and worked for four years at Thousand Islands National Park. She became interested in the 19th century lighthouses of the Thousand Islands in 1997, and has been researching them ever since. Mary Alice provided TI Life with articles about Wolfe Island’s Lighthouses, Fiddler's Elbow, Lindoe Island Lights, the Ogdensburg Harbor Light and Cape Vincent Harbor Lighthouses; click here to see them all.