Important to Note:

Recently in the news, the Marine Museum of the Great Lakes at Kingston, the very site where this story takes place, has been given 120 days to vacate the premises by the new, private owner. They must be out no later than Tuesday, August 23, 2016. The museum's dedicated staff and volunteers are now moving forward with existing contingency plans, which include planning for and executing a potential move.

As this site itself, a thriving shipbuilding centre since the early 1830's, it would be a shame to let it disappear quietly, like the shipyard itself after 1968. It was saved then from total destruction and can be saved now. Kingston bills itself as the city "where history and innovation thrive".

Let's prove it.

Please contact the Museum by phone at 613 542 2261 or e-mail: marmus@marmuseum.ca, to add your name and contact info to the list of volunteers, with ideas to help.

Editor, Susan W. Smith and author, Captain Brian Johnson, May, 2016

|

Springtime on Wolfe Island

High on top of a hill, surrounded by budding lilac bushes, the one room brick schoolhouse, with its two outdoor privies, commanded a view overlooking the bay and the small village of Marysville below. Inside, bored with their lessons, two young girls, Agnes Greenwood and Carmel Cosgrove continued to whisper and giggle, despite warning glances from their teacher.

Visiting high school inspector C.P. Smith removed his glasses. Enough was enough.

“You. With the big brown eyes. Stand up!” The taller girl stood up, giving her companion a nervous glance.

“How many peas in a pod?” The school inspector demanded.

Looking at her friend, then back at the teacher, Carmel stammered, “I… I don’t know sir?”

“I asked, how many peas… are there… in a pod? ANSWER!” He shouted, slapping a ruler on the desk in front of her. The class was silent. Nobody moved. The teacher, arms crossed, was frowning.

Feeling helpless, frightened and embarrassed, the tear filled, brown eyed girl swallowed, then started to speak, weighing her words slowly, “I… I don’t know… you see, my papa never… he never told me…”

“What’s your papa got to do with it?!”

Carmel Cosgrove seized the moment. “He’s… he’s our teacher. Standing right there. Ask him yourself.”

That was the last time anyone would intimidate Carmel Cosgrove. Ever.

Several years later, this same man came face to face with a big nurse dressed in spotless whites, her cap poised perfectly square on her head at the railroad station in Kingston. Recalling the incident, Cosgrove started to laugh. “I stood up suddenly, matching him eye to eye. Actually, I looked down a bit. He stopped then stepped back one pace. I said, ‘Hey, how many peas in a pod, mister?”

“I… I beg your pardon?”

“I said, just how many peas… are there… in a pod, mister?”

“Oh my word,” he said, adjusting his specs. “That was you, years ago on… Wolfe Island, was it?”

“You’re damn right it was me. What’s your answer?!”

“Ha. He just sat down and started to fidget with his hands. So I sat right across from him until the train came. He never looked up. Not once. Not even on the train.”

Carmel Mary Cosgrove

Carmel Mary Cosgrove passed away on February 1, 2007 at 94 years of age. The feisty Wolfe Islander was 89 when we sat down together in her kitchen, working on a history project, and instead started talking about her life. Born and raised on Wolfe Island, Cosgrove never forgot that lesson in face-to-face confrontation. It was probably the reason the spirited octogenarian lived independently in her own house in Kingston, while still keeping a cottage on Wolfe Island, and most definitely the reason she chose the profession she did.

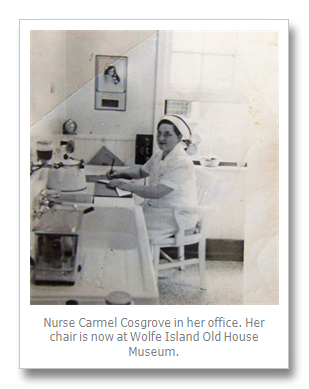

Carmel Cosgrove was the plant nurse for the rough and tumble Kingston Shipyard between 1944 and 1968. Twenty-four years in the toughest area of town.

The fourth oldest child of James Dufferin Cosgrove and Mary Louise Spoor, Carmel Cosgrove, her two sisters and seven brothers attended the one room red brick schoolhouse in the village. Their father, Duff, was their teacher. Following this, they all attended the continuation school, which was also on the island, before sailing across the pond to various high schools in Kingston.

Seated in her kitchen, we had several photo albums open on the table. She remembered in detail each face in every picture. “I finished at Kingston Collegiate and then secretly started training to be a nurse at the Rockwood Hospital,” Carmel said. Then smiling, she added, “Papa wanted me to be a teacher. He would have died if he knew I was going through for a nurse.” Cosgrove completed her training at St. Joseph’s Hospital in Toronto. It was on one of those commuter trips that she met and stared down the man who had scared her as a child. The shy young girl from Wolfe Island now had the steely look of a determined, self-confident woman not to be messed with. It would serve her well in the dangerous years ahead.

Training completed, Cosgrove soon despised the big city life of Toronto and the humdrum routine of a hospital ward. She loved her profession but longed to return home to familiar surroundings. Her trips home ‘boosted her batteries’ but gave way to a long face on the return train trip to Toronto. During breaks at the hospital in the big city she would daydream of her childhood back on Wolfe Island.

“We packed salt pork and corned beef in snow. We cut holes in the ice, in the bay, for drinking water. We had bricks for heating feet or hot water in whiskey bottles. We sliced onions for chest colds, saved newspapers and stuffed windows with them, wrapped up our woolens to keep out moths. I remember getting to school with wet feet, from walking on the ice in the spring and paying ‘Tricky’ McDermott to use his plank bridge, over a crack in the ice-road.

The word home for Carmel Cosgrove encompassed not only life on Wolfe Island, but the ways and means of getting there – crossing the three-mile gap of Lake Ontario, by horse and cutter, across the ice in winter and especially by steamer in the summer. As a child, she loved the trips to and from the island on the old paddlewheel steamer “SS Wolfe Islander.” She points to a picture of the boat that hangs in her front hall (mine now). With fond memories she can recollect almost everyone who worked aboard and never hesitated to ‘seize the moment’ on occasion. “William Armstrong was the mate. He used to light the red and green lamps (navigation lights, red for port, green for starboard) inside the cabin, so the wind wouldn’t blow the match out. Sometimes, in a hurry, he got them backwards, when he set them out. I told him so; ‘What’s the difference?’ he said. ‘They’re both lit!’”

Later, we took a drive down to Ontario Street and to the old Kingston Shipyard Drydock opened by Canada’s first Prime Minister, Sir John A. MacDonald, a former Kingston boy, performing one of his last acts as Prime Minister, shortly before he died. This is now the site of the Marine Museum of the Great Lakes at Kingston. Inside, on display, is a treasure trove of more than one hundred years of early Kingston and region history, especially pertaining to marine shipbuilding and transportation, the very backbone of early Kingston and area. Just outside the drydock itself, floats the museum ship Alexander Henry (she would be moved into the dock a little later) on display. In the quiet parking lot, Carmel Cosgrove gets out and looks around. It’s a far cry from the wartime shipyard of 1944.

During the latter part of the Second World War, when production and demand at the Kingston Shipyard – in business since 1910, a subsidiary of Collingwood Shipyard – went into overdrive, employing 1500 workers on site, accidents were bound to happen. As in any heavy industrial environment, workers had to have ‘eyes in the back of their head’ for their very lives depended on it. But this was wartime with productivity as the goal and sometimes it came at a heavy price. The men knew this of course, and accepted it. Danger lurked everywhere. There was no ‘health and safety committee’ for protection. It wouldn’t exist for another fifty years. Indeed, there was no proper medical facility on site. There was always the drydock, to fall into. Cranes and cables moved overhead and on the ground constantly. Hammers swung everywhere. Steel beams and plates swung overhead. Underfoot, there were red-hot rivets than would rain down from above without warning. If a doctor was needed, he was called.

Carmel Cosgrove fell in love with the place and applied for a position as ‘plant nurse’. “I went in there and applied for the job, but Superintendent Don Page didn’t want me. He didn’t think I could handle it,” she said, pointing out where the main office had been. She turns and points in another direction. “So, I went into Tom Bishop’s office (the manager) and I said, ‘If you’ll just give me a chance, I’ll work for a month for nothing. Then, if you’re not satisfied, show me the gate.’” Tom Bishop took her up on it, and when the month was up, she appeared at his office.

“Get the hell back to your post nurse,” Bishop said. “No one can handle this bunch and the job like you can. You’re hired.”

Cosgrove then turns and looks at the big, silent drydock and is lost in thought for a moment. Someone jogs by but she doesn’t notice. “Albert Muldridge operated the steam crane over there. He was 41 years of age when it flipped over into the empty drydock, landing upside down. He was scalded to death. We were four hours getting his body out.

“Over here, Matt Campbell was crushed between the cement abutment and the crane. I helped pick up the pieces for Reid’s Funeral Home. And then Leo Carigg got too close to the crane and his overalls became caught. When she swung, it threw him into the empty drydock. Killed instantly.”

Cosgrove pauses for a minute again and then looks toward a large apartment building, on the waterfront beside us. “That’s where my office was. My ol’ stomping ground. From my window I watched the corvettes launched sideways, right over there (she points). Eighteen corvettes and six deep sea tugs.”

Two more joggers run by. Carmel’s eyes are fixed on something near the end of the dock. Then she turns around. “You know,” she began, “it’s a sad fact, but true, that buildings have a way of outliving their usefulness. Most of them are gone now. Smokestacks and lunch pails seem to be a no-no in our fair city. It would be nice if there were one or two benches reserved for former shipyard employees here so that we might have a place to sit in our twilight years and reminisce about happier, bygone days…”

Today, there is such a park, right in front of the drydock with the Marine Museum of the Great Lakes at Kingston right behind. A manicured lawn with flower beds and trees, planted with memorial plaques underneath. A large, stone memorial is also fixed in place, commemorating the sacrifice of many local merchant sailors, of World War II, as well.

As I helped her back into the car, Carmel, once seated, asked me a question. She looked at me seriously. “Why do you suppose they launch a boat backwards?”

I thought for a moment. Stumped. “I really don’t know. Why? Do you?”

“I didn’t know either. But one day, just over there, one of the guys told me. He said, ‘Well nurse, they’re a little like you. They’re much heavier in the after end.’”

Carmel Cosgrove had seized the moment. Again.

By Brian Johnson, Wolfe Islander III captain, retired.

Brian Paul Johnson is a recently retired captain of the Wolfe Island Car Ferry, “Wolfe Islander III.” He worked for the Ontario Ministry of Transportation for more than 30 years. We also often see him pass-through the islands as Captain of the “Canadian Empress.”

Today, Brian combines his marine career with writing. Fascinated by stories and legends of the 1000 Islands area, he has written for the “Kingston Whig Standard,” “Telescope Magazine,” the “Great Lakes Boatnerd” and the website: “Seaway News”. Brian co-edited “Growing up on Wolfe Island”, a compilation of interviews and stories with Sarah Sorensen. He is also a past president of the Wolfe Island Historical Society.

And best of all, he is about to publish his latest book… Watch for more news in a forthcoming issue of TI Life. To see all of Captain Johnson’s articles for TI Life, Click Here.

This story first appeared in the “Kingston Whig Standard” as 'Life and times of a Shipyard nurse' on Dec 31, 2001. We think it is a fitting story to bring attention to the plight of the Kingston Marine Museum.