|

Editor’s Note: 2017, is the year of the centenary of Canada’s Forgotten Victory. A new monument has been unveiled and dedicated in France to commemorate the many soldiers sacrificed at the Battle of Hill 70 during World War I.

The project was created and completed by a group of volunteers from Kingston, ON, headed by Col. Mark Hutchings.

It was from August 15th to the 25th 1917, that the Canadian Corps fought and died during the Battle of Hill 70. The project’s website has links to search where families of soldiers who served at Hill 70 can access their relatives service files at the Library and Archives of Canada and those who sacrificed their lives can be found in the Canadian Virtual War Memorial at Veterans’ Canada and at the Commonwealth War Graves Commission site.

Six Victoria crosses were won at the Battle of Hill 70, more than had been won in any previous battle in WWI.

Dr. John Scott Cowan, Principal Emeritus, The Royal Military College of Canada in Kingston, wrote this short historical review and shares it with our readers.

|

How Lt Gen Currie’s resistance to a bad order turned the Canadian Corps into a national army and hastened Canadian independence

Canadian students learn about Confederation, and most of them believe that Canada ceased to be a colony and became a country with the passage of the British North America Act in 1867. Not so. The BNA Act provided only for internal self-government of the colony of Canada. In the 47 years from Confederation to the outbreak of the Great War in 1914, no country had an embassy in Canada, nor did Canada have any embassies or high commissions abroad, except for a High Commissioner to the UK from 1880, with limited duties and limited access to information. If Canada wished to communicate with a nation state, the Governor General would write to the Colonial Office in London, who would forward the communication to the Foreign Office, who in turn would move the question to the British Embassy in the country of interest. On occasion a Canadian observer might go along to subsequent discussions abroad.

On 4 August 1914, the same day that Britain declared war on Germany, Sir George Perley took up the post as Canada’s High Commissioner to the UK. But Sir George was not allowed to see the correspondence between the Governor General and the Colonial Office.

On 4 August 1914, the same day that Britain declared war on Germany, Sir George Perley took up the post as Canada’s High Commissioner to the UK. But Sir George was not allowed to see the correspondence between the Governor General and the Colonial Office.

At the outbreak of the war, Canada declared war on no-one. Britain did it for all of the Empire. Canada merely got to decide how it would react to being at war.

The first commander of the Canadian Corps was Lt Gen Edwin Alderson, a British officer appointed by Britain after consultation with Canada. He was reprimanded early in the war by the War Office in London for responding directly to questions from the Canadian government in Ottawa. He was reminded that all communications with Ottawa were to be passed through the War Office. Thus in the early stages of the war, Canada was seen merely as a source of manpower for the British Army.

When the war broke out, Canada was a nation of perhaps seven and a half million people. Some 680,000 went into uniform, about 625,000 of them into Canadian uniform, and about a half a million went to Europe. About 66,000 died and 172,000 were injured or fell gravely ill during operations.

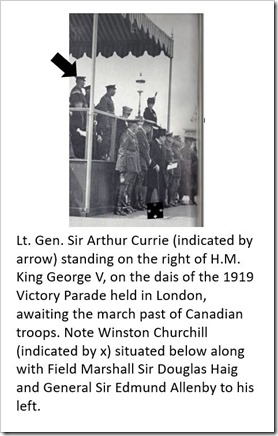

But in 1919 Canada had a seat at the negotiations for the Treaty of Versailles, a seat in the League of Nations, and the right to be elected to the League Council. Effectively, Canada was a nation state, and somehow four and a half years had done what 47 earlier years had not. Canada had acted like a nation, and so came out of the Great War as a nation.

In Canada students are taught variously that complete independence from Britain was achieved by the Statute of Westminster (11 Dec 1931) or by the patriation of the Constitution in 1982. But no-one is really so naïve. Paperwork follows later to solemnize the facts on the ground. Paperwork never leads events, it follows them.

Canada’s war of independence was the First World War, the so-called Great War. Unlike the Americans, our war of independence was not fought against the entity from which we became independent, but alongside it. We started the war as a colony and ended it as an ally.

The autonomy came gradually. The efforts in London of Sir George Perley, in both his roles as Acting High Commissioner and simultaneously as Minister of Overseas Military Forces of Canada, and those of his successor in this second role, Sir A. Edward Kemp, were of great importance.

But the real autonomy came from the performance of the Canadian Corps and its first Canadian commander. All Canadians learn about the Battle of Vimy Ridge, which began on 9 April 1917. It was the first action in which all four divisions of the Corps fought. At the time the Corps was commanded by LGen Julian Byng, a British General who later that spring got promoted to command the British 3rd Army. In the 1920’s, as Lord Byng of Vimy, he was Governor General of Canada.

But the real autonomy came from the performance of the Canadian Corps and its first Canadian commander. All Canadians learn about the Battle of Vimy Ridge, which began on 9 April 1917. It was the first action in which all four divisions of the Corps fought. At the time the Corps was commanded by LGen Julian Byng, a British General who later that spring got promoted to command the British 3rd Army. In the 1920’s, as Lord Byng of Vimy, he was Governor General of Canada.

His senior division commander was Maj Gen Arthur Currie, who was the chief planner for Vimy, basing much of his planning on lessons learned from the French defence of Verdun. Because of meticulous planning and rehearsing, recent technological advances, and good leadership, the Canadian Corps succeeded where earlier French troops had twice failed. Two unsuccessful French attempts to take and hold the ridge in May and Sept of 1915 had cost them about 150,000 casualties. During a period with little other good news, the Canadian Corps victory got tremendous attention. It has since taken on iconic significance for Canadians, so much so that few

Canadians know that of the 170,000 men in the allied attack on Vimy Ridge that day, only about 97,000 were Canadian. In some ways, it was not a Canadian battle, but a British battle with high Canadian content and a Canadian planner. But exactly two months after the start of the assault on Vimy Ridge, a Canadian, Sir Arthur Currie was promoted to Lt Gen and given command of the Canadian Corps. On 7 July 1917, when Currie had been corps commander for under a month, he received orders from Gen Horne, commander of the 1st British Army, of which the Canadian Corps was a part, to attack and capture the small industrial city of Lens, somewhat north of Vimy. Currie refused.

Had Currie been a newly minted British Lt Gen, he probably would have been sent home, but he wasn’t. Field Marshal Haig and Gen Byng both agreed with Currie’s reasoning, and counselled a rethink.

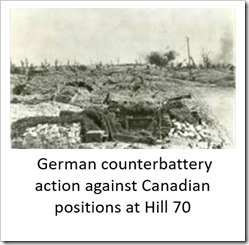

Why had Currie balked? For good reason. On the whole, Canadian generals did their own reconnaissance, and British generals rarely did. Perhaps that was a residuum of the class system. Indeed, the casualty rates for Canadian general officers in the corps were higher than for the corps as a whole (42% vs. 37%), partly as a result of this. Currie had done his own recce of Lens and considered it a killing ground, as it was dominated by German artillery on the hill to the north-west. From that hill, the German gunners could see the entire Douai Plain, the flat coal-mining area east of the Vimy Ridge. Currie made clear that he would prefer to attack and capture the high ground first.

Currie’s view prevailed. Three days later, on 10 July, after a meeting of commanders in his HQ, Horne issued revised orders to his army, including to the Canadian Corps (the new orders went to 1st Corps, 11th Corps, 13th Corps, Canadian Corps, and 1st Brigade, Royal Flying Corps). It reads, in part, “ ...On discussion with the GOC Canadian Corps, and on the allotment of additional artillery to the 1st Army, it has been decided to amend the objectives for the Canadian Corps”. The orders moved Currie a bit further north along the front, and essentially .turned that section of the front over to Currie. But .it is the first mention in army-level orders of “the high ground NW of Lens”, which subsequently became known as Hill 70.

Currie’s view prevailed. Three days later, on 10 July, after a meeting of commanders in his HQ, Horne issued revised orders to his army, including to the Canadian Corps (the new orders went to 1st Corps, 11th Corps, 13th Corps, Canadian Corps, and 1st Brigade, Royal Flying Corps). It reads, in part, “ ...On discussion with the GOC Canadian Corps, and on the allotment of additional artillery to the 1st Army, it has been decided to amend the objectives for the Canadian Corps”. The orders moved Currie a bit further north along the front, and essentially .turned that section of the front over to Currie. But .it is the first mention in army-level orders of “the high ground NW of Lens”, which subsequently became known as Hill 70.

Between 15 and 20 August, 1917 three divisions of the Canadian Corps (plus one in reserve) battled five German divisions and took and held Hill 70. The attack cost the Corps some 3,500 casualties, and the clever and innovative defence against a massive counter-attack cost another roughly 2,200 casualties. But the Canadians held, and to this day no-one knows the German losses, but they are believed to have exceeded 20,000.

It had been a hard fight; six Canadians were awarded the VC for their actions at Hill 70, somewhat more than the four Canadians awarded the VC for valour at Vimy Ridge.

After that Currie had new status. He was viewed as having superb judgement. Army commanders treated him carefully (Horne, 1st Army, and Rawlinson, 4th Army). He largely got his orders from Haig, with the relevant army commander also present. Suddenly the Canadian Corps had become a national army, and not just another unit of the British Army.

In the months that followed, Currie differentiated the Canadians even more. In January 1918 he refused triangulation of Canadian divisions, and in doing so refused personal promotion to Army commander. At that time, British divisions went to a structure which included three brigades, each with three battalions of infantry (hence the 3x3, or “triangulation”). British battalions were also understrength by then, often about 600.

Currie believed that triangulation could cause pointless casualties, and preferred to fight divisions at full strength. He kept the infantry in the Canadian divisions at three brigades, each with four battalions of infantry. These were over-strength battalions too, at about 1100 men each, as each carried 100 of their own reserves. Had he agreed to triangulation, he would have had at least seven divisions in two corps. Anything over six is an “army”. He kept the Canadians as a corps rather than an army, eschewing the complexity of having two corps HQ and an army HQ. But the Canadian Corps was by then larger and more powerful than most British armies, and each of the four Canadian divisions was equal to at least 1.7 British divisions. Haig started adding to the impact of the 156,000 strong Canadian Corps by placing additional British divisions under Currie as well for the last year of the war.

The successful battle for Hill 70 was the watershed. After that, the Canadian Corps was viewed as a national allied army, and Currie as a national force commander. His effective reporting lines changed. The Corps became different. By 1918, a Canadian division would have one automatic weapon for every 13 men, vs. one for every 61 men in a British division. A Canadian division would have about 13,000 infantry and about 3,000 engineering troops, vs. about 5,400 and 650 for a British division. And the Canadian Corps had 100 more trucks than any British corps. There was a distinct Canadian way of war. In the period known as the “100 days”, the Canadian Corps drove through and defeated 47 German divisions, one more than the 46 defeated by 650,000 Americans in the Meuse-Argonne Campaign. But the Canadians took half the casualties of the Americans, and used twice the number of artillery shells. Currie’s slogan was “Pay the price of victory in shells, not men”.

The important decision taken during 7-10 July 1917 to focus Canadian effort on Hill 70 was a crucial way station on the road to Canadian independence. The instrument of that Canadian differentiation was the resolve and insight of a former schoolteacher, insurance company manager and real estate speculator called Arthur Currie, who refused an order that was not in Canada’s interest. But his bold choice to protect his men would have had little ongoing impact if his judgement hadn’t been vindicated by the events of August 15-20, 1917, when the Canadians, under his command, won the battle for Hill 70. Victory at Hill 70 dramatically hastened Canada’s independence.

The successes of the Canadian Corps, particularly those under Canadian command, beginning with Hill 70 and culminating with the Battle of Amiens and the subsequent “hundred days”, achieved great recognition for Canada and strengthened Borden’s hand to such an extent that, during the Versailles negotiations, Borden stood in for Lloyd George from time to time when the latter could not attend.

Borden had set the stage for this throughout the war by his determined and effective efforts in in pressing for a distinctive Canadian role and for the Canadianisation of the Corps. In person, and through the fine work of Sir George Perley and Sir A.E. Kemp, his representatives in London, Borden adroitly exploited Currie's push for a degree of autonomy to further the cause of Canadian independence. In this the military and political spheres were in perfect harmony.

That is why a small group based in Kingston has just completed a three part program, consisting of (a) the construction and dedication of a major monument at Loos-en-Gohelle in France, (b) publication of the definitive, peer-reviewed history of the battle, Capturing Hill 70, which was published by UBC Press, and is a best-seller, and (c) the preparation and delivery of extensive teaching materials to every high school in Canada, now completed.

|

Obelisk and Platform

Photo courtesy Hill 70 Project

|

Photo courtesy Hill 70 Project

|

A monument to the memory of the Canadian Soldiers who fought and died for Victory at Hill 70.

The battle took place along the Western Front on the outskirts of Lens in the Nord-Pas-de-Calais region of France.

For more information and to contribute to this important project, see http://www.hill70.ca/

|

|

Patron

His Excellency The Right Honourable, David Johnston, C.C., C.M.M., C.O.M., C.D. Governor General of Canada

Honorary Advisors

The Rt. Hon. Beverley McLachlin, P.C.

The Hon. John Fraser, P.C., O.C., O.B.C., C.D., Q.C.

The Hon. Peter Milliken, P.C., O.C.

The Hon. Bill Blaikie, P.C.

The Hon. Perrin Beatty, P.C.

The Hon. Bill Graham, P.C., Q.C.

Gen. John de Chastelain, C.C., C.M.M., C.D., C.H.

|

Board of Directors

Chair: Colonel Mark Hutchings

Dr. John Scott Cowan

Warren Everett

Douglas Green

Arthur Jordan

David Parker

Hill 70 Project Team

Education

Susan Everett

Robert McGaughey

Elva McGaughey

Anne Richardson

Don Richardson

Robert Engen

Media

Mark Blevis

Bill Neill

Cristina Wood

|

Memorial Team

Sarah Murray

Tim Murray

Sean Murray

Thady Murray

Fundraising Team

Robert Baxter

Henrietta Southam

Maggie Shepherd

John Macdonald

Ceremony and Protocol

John Roderick

Howard Coombs

Christopher Sproule

John Macdonald

|

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________

By Dr. John Scott Cowan. Principal Emeritus, The Royal Military College of Canada

John Scott Cowan studied physics and physiology at Toronto. A post-doc at Laval University preceded 24 years at the University of Ottawa as professor, chair of physiology, and then vice-rector. Vice-principal at Queen’s University before becoming principal of the Royal Military College of Canada (1999-2008), he has also worked extensively in labour relations, and has flown some 60 aircraft types. Research in physiology co-existed with defence issues, starting with a 1963 monograph on defence policy. Recently he has focussed on asymmetric threats, piracy, the characteristics of the profession of arms, and defence education. He was president of the CDA Institute 2008-2012, and chair of the Defence Advisory Board of Canada 2010-2013. In early 2017 he retired as the Honorary Colonel of the Princess of Wales’ Own Regiment.