LIDAR, which stands for Light Detection and Ranging, is a remote sensing method used to survey and map the surface of the Earth. For the last few years National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and New York State have been using airborne Light Detection and Ranging (LIDAR) to map New York State. The results of this mapping have been released to the public and are available online.

LIDAR data has many useful applications in business, industry and government. It also has an application in the field of archaeology for surface mapping. With accuracy, in the tens of centimeter range and the ability to remove the forest canopy and vegetation - features that may be indistinguishable on the ground, can now be revealed.

Longest continually occupied island in the Thousand Islands

Carleton Island was the first island in the Thousand Islands to have a European settlement and to be continually occupied to the present day. It was called Deer Island, when it was first used by British merchants in 1774. It served as a transfer point for merchandise and equipment, between Lake Ontario and the St. Lawrence River. Small vessels could navigate the Thousand Islands while larger sailing ships operated better on Lake Ontario.

In 1777, during the American Revolution, the island served as a staging area by a British army, under General Barry St. Leger. This was the western army of the Burgoyne Campaign. This campaign was the first major British defeat of the War. The loss of a field army, and the access to the Mohawk Valley, caused the British need to supply the western posts at Niagara, Detroit and others, via the St. Lawrence River. They used much the same route as the modern-day St. Lawrence Seaway.

In August 1778, Governor General of Canada, Frederick Haldimand, instructed Lt. William Twiss, Royal Corps of Engineers to select a site at the Eastern end of Lake Ontario as part of this supply route. After a review of sites, Twiss with the assistance of John Schank of the British Navy, selected Deer Island. In late August of 1778, the Island was renamed Carleton Island and construction of docks, shipways, a hospital, fortifications and barracks were started.

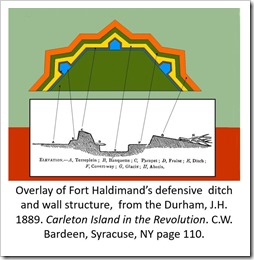

After designing the major earthworks known as Fort Haldimand, Twiss returned to Montreal and Lt. James Glenie, Royal Corps of Engineers, was left to oversee construction. By 1782, the entire west end of the island was occupied. Records indicate as many as 1500 soldiers and sailors, over 500 Indians and hundreds of displaced loyalists were on the island.

With the signing of Treaty of Paris in 1783 ending the American Revolution, new military construction on Carleton Island ceased. There was a need to resettle Loyalist families, now displaced from the Mohawk Valley. The old French post at Frontenac was re-occupied, resulting in the settlement of Kingston, Ontario.

The base at Carleton Island, which was one of the most vital sites in the province of Canada, between 1778 and 1783, was slowly reduced in size. It was eventually ceded to the US, as the only land change resulting from the War of 1812. After that, it played a role in the lumber trade before the first half of the ninetieth century, and before the coming of the Golden Age of the Thousand Islands and the construction of Carleton Villa, at the head of the island.

Artifact of the Revolutionary War

Carleton Island today is entirely private owned. There is no historical society or museum dedicated to the British military occupation of Carleton Island. Over 25 acres of the west end of Carleton Island are on the National Register for Historic sites.

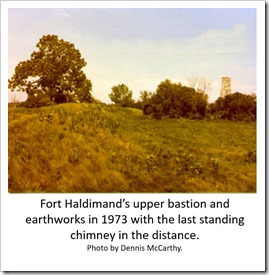

Fort Haldimand was most noted for its massive stone chimneys that were part of the barrack system for the fort. Over 20 of these stood over 20 feet tall and slowly over the years, the chimneys succumbed to the elements and fell. The last chimney fell in the 1990s, after having stood for 200 years.

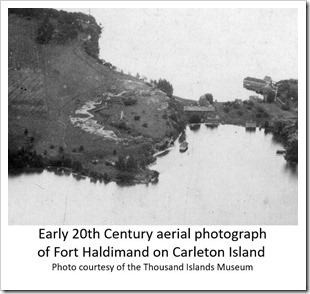

Historic photographs at the Thousand Islands Museum and the Cape Vincent Museum show that a large section of the earthworks designed by Engineer William Twiss survived into the 1970s. After the War of 1812, the site was used as a pasture, because of its cleared land and little surface soil. In the 1950s part of the fort’s center and eastern walls were bulldozed.

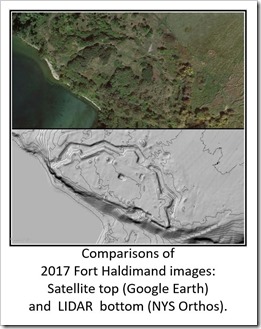

When land development started in the 1980s and cattle farming ended, the remains of Fort Haldimand started to be reclaimed by nature. By comparing aerial photography, from before 1970 and current satellite images, it can be seen that the earthworks are no longer visible.

When land development started in the 1980s and cattle farming ended, the remains of Fort Haldimand started to be reclaimed by nature. By comparing aerial photography, from before 1970 and current satellite images, it can be seen that the earthworks are no longer visible.

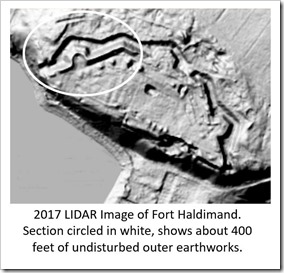

The magic of LIDAR

With the capability of LIDAR to remove forest canopy and vegetation from images, features on Carleton Island that may not even be distinguishable on the ground, can now be seen and mapped. LIDAR is now confirming that some of the Revolutionary War earthworks on Carleton Island still exist. As artifacts of the American Revolution, which have been fending off the elements for almost two-and-a-half centuries, they are extremely rare.

I first saw Fort Haldimand in 1973, when I was a volunteer for an underwater survey of a Revolutionary War ship, sunk in North Bay of Carleton Island, near the remains of Fort Haldimand. The survey was under a joint permit, with the New York State Divers Association, in cooperation with the Thousand Islands State Park and Recreations, acting for Historical Preservation of the State of New York Office of Parks and Recreation.

I first saw Fort Haldimand in 1973, when I was a volunteer for an underwater survey of a Revolutionary War ship, sunk in North Bay of Carleton Island, near the remains of Fort Haldimand. The survey was under a joint permit, with the New York State Divers Association, in cooperation with the Thousand Islands State Park and Recreations, acting for Historical Preservation of the State of New York Office of Parks and Recreation.

At the same time as the underwater survey was taking place, a land archaeologist working on Fort Haldimand, offered me a tour of the fort. The archaeologist was Bill Ennis from Baldwinsville, NY.

Bill gave a tour pointing out interesting things, and I couldn't believe that the area was so well preserved. The cattle that were on the island kept the grass short, and there was almost no vegetation. The plane of the fort, banquette (step to wall) and parapet (wall) looked as if the British had just left. The last remaining chimney still stood over 20 feet tall, and it was almost entirely intact. Bill Ennis’s collection was acquired by the Rochester Museum and it has been on display in the past but is not currently. This is one of several collections of Carleton Island and Fort Haldimand artifacts. Others are at the New York Historical Society in New York City, the State Museum in Albany, and SUNY Oswego, to name a few.

Current airborne LIDAR is just the beginning. Starting to appear on the market are personal drones with thermal infra-red and 3d mapping. Hopefully more of the 1000 Islands’ past will be uncovered.

[More information on Carleton, I invite you to attend my presentation ‘The History of Carleton Island’ on Wednesday July 11th2018, at the Thousand Islands Museum’s History at Noon Program in Clayton, NY. Fort Haldimand information can also be found at www.forthaldimand.com and in the book The Old Fort, a reprint of the book “The Old Fort, Carleton Island in the Revolution” 1889 written by Major James H. Durham with a current introduction written by Kathryn C. McCarthy.

More information on LIDAR images:

http://desktop.arcgis.com/en/arcmap/10.3/manage-data/las-dataset/lidar-solutions-creating-raster-dems-and-dsms-from-large-lidar-point-collections.htm]

By Dennis McCarthy

Dennis McCarthy retired in 2009, from his professional career in engineering management in the Consumer Electronics and CATV industries. Having traveled to 28 countries in his business profession, he now prefers to spend his time with his wife Kathi, living near Cape Vincent, NY and enjoying the Thousand Islands and St. Lawrence River. A certified scuba diver, for over 40 years, he made his first dives in the River in 1971. Co-founder of the St Lawrence Historical Foundation (SRHF) in 1993, he helped organize the underwater survey of the Niagara Shoal Wreck, which was identified as the French war ship L'Iroquois that sunk in 1761 (St. Lawrence River Historical Foundation Inc. website)

He and his wife Kathi (See Seeing Underwater… October 2011 and Kathi and Dennis McCarthy’s Discoveries …in March 2011.) now spend their time writing and publishing popular books and regional calendars. In addition, Dennis hosts the popular Thousand Islands River Views Facebook page. It is from here that he shares many photographs with TI Life.

A similar article was published in “Thousand Islands Sun.”January 24, 2018 by the Thousand Islands Museum News.

(When looking at the LIDAR and other NY State links, search under Carleton Island or the location of your choice.)