Had enough of The War of 1812?

Not really?

Good, because I feel the same way.

Ever since the Kingston Historical Society announced a Bicentenary commemoration project, “Sideshow or Main Event: Putting the War of 1812 into Regional Contexts,” I have been absorbed by the subject. I started reading and re-reading books and articles and was perplexed by conflicting opinions about “The War That Wasn’t Won” - but shaped the boundaries of our Dominion.

I created a “War of 1812” file, appropriately or not so appropriately encased in a blood-red folder. It started with references to news stories of yesteryear, and grew with learned essays and reports of spectacular re-enactments at Bath, Wolfe Island and Gananoque — one of which I attended. The file was fattened by literature beautifully printed by institutions with grants from the federal government, i.e. the Bicentennial commemorative map “Along the St. Lawrence,” which proudly proclaims. “Our region was pivotal in defending Canada.”

Was the Kingston-St. Lawrence action just a sideshow, or does the title refer to the North American battles in comparison to the British-French confrontation in Europe?

Something is missing, and I’m still searching. I’m trying to relate to a 200-year-old conflict that occurred before Canada was a formal nation. I want to know what Kingston was like at the time, and how the small community was affected?

Despite the scads of information and my English heritage, I found it difficult to relate to a British conflict with the United States, 55 years before Canada became a nation. And I seek a memorial in stone. As one of the 100,000 surviving veterans of the Second World War, the 1939-1945 experiences are permanently marked and commemorated each year on Battle of Atlantic Sunday and/or Remembrance Day.

City Park is one big memorial to Kingston’s artillery, air force and regimental units that marched out of the city and many paid the highest price in defence of freedom. The Great War of 1914-18 was my father’s war—even though he also volunteered and served in “my war.” The Boer War was my grandfather’s war.

Every veteran, including those of most recent conflicts in the Gulf, Afghanistan and Libya, and the Korean war, have memorial dates, monuments and cenotaphs to mark their service. But nowhere in this great garrison city is there a prominent memorial where citizens can pause and reflect on The War of 1812.

To fill the void, I turned to my library to try and reflect on the ancient struggle between two basically English-speaking nations. Pierre Berton’s War of 1812, 911 pages embracing The Invasion of Canada (1980) and Flames Across the Border (1981), was engrossing with vivid prose and detailed maps, but few references to Kingston, and overall much too much info for a quick fix on the complex international situation.

I wanted some source that would localize the story — that would personally connect me and tell how Kingston fared between 1812 and 1815. Bringing some daylight to the question, I found a companion to the PBS television special on the war more helpful [See http://www.pbs.org/wned/war-of-1812/ for 3 min. video] . The War of 1812,B b John Grant and Ray Jones, this beautifully illustrated guide to the battlefields and historic sites of the 1812 war was most enlightening, particularly the chapter on “Warships on an Inland Sea,” which featured not Fort Henry, but Fort Frederick, and succinctly described the “escape” or “flight” of the outgunned and outmanned Royal George into Kingston harbour.

I longed for a more Kingston-oriented perspective and turned to my available historic records — notes about the war gleaned in years of microfilm searching for general and sports news. There in The Kingston Whig-Standard of Oct. 24, 1950, were the “Impressions of a Transient” - a half-page article on the financial boom that the 1812 war brought to Kingston, as other wars had done.

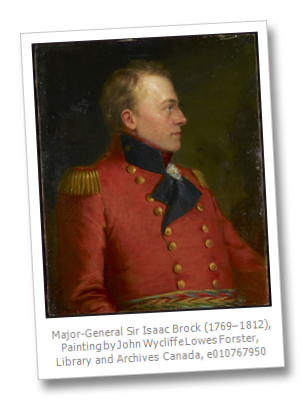

Written by Mabel T. Good with salutes to Sir James Lucas Yeo, General Brock and Laura Secord, were logged details of the schooners, luggers and gunboats built in Navy Bay. It concluded with this insight: “Though Kingston remained unchallenged, to Canadians throughout the ‘toil and troubles’ of 1812-1814, gallantry, chivalry, prowess and the quickly fading ’bubbles of honour’ marched in her muddy streets and floated over her stone bulwarks.”

A succinct thought, but how could I really reach out and touch the past and feel how Kingstonians fared? I turned to an even more ancient clipping from The British Whig of February 1901. Entitled “KINGSTON WAS IN PERIL,” the one-column story told how the people of Kingston “rose loyally” against a Yankee attack that did not materialize.

The author, noted historian Dr. William Canniff, described how two cannons and a telegraph were set up at Herkimker’s Point with a view of the upper gap at Amherst Island and exchanged shots with one of a fleet of 14 American ships. The schooner Simcoe received several shots and sank when it reached Kingston.

“The artillery and troops marched along opposite the fleet to Kingston and were paraded in a concealed spot behind the jail,” he reported. “It was the general expectation that the Americans would attempt to land; shots went flying over the buildings. Every step was taken to frustrate any designs.”

The woods around Kingston and Point Henry were cut down to prevent surprise, but the “Statesers” did not attack. They landed their forces lower down the St. Lawrence, where they were repulsed at the famous Battle of Crysler’s Farm.

But what was Kingston really like at the time? I turned to Historic Kingston and a 1983 essay by Royal Military College professor Jane Errington. In “British American Kingston and the War or 1812,” Ms. Errington, then a doctoral student at Queen’s University, told of “a mature, sophisticated” town of 1,200 that boasted a number of shops and taverns, a courthouse, a jail, two churches and one newspaper.

She quoted liberally from the recently established Kingston Gazette, which was filled with reports from American Federalist newspapers that editor Stephen Miles received throughout the war. “For 20 years, the United States had been Kingston’s window to the world,” she said, “and the inhabitants of the town did not hesitate to look to family and friends for their understanding of international events in general.”

Kingston, isolated as it was from other British North American settlements, had its closest neighbours in the new republic. Quoting the Cartwright papers, she said, the leading citizens had sent their children south to school for years and made frequent visits to family and friends in New York and New England. She debunked “the Loyalist myth” and concluded that throughout the war “the elite of Kingston remained British-Americans” — a name that lived for years on Kingston’s most noted hotel.

These insightful comments filled much of the void in my thinking about 1812 Kingston, but my findings still lacked a personal connection. At Kingston’s naval reserve base, HMCS Cataraqui, I found a relic from the war — wooden anchors from warships built at Navy Bay. Remarkable, but not enough. I turned to my old town of Gananoque, which has done a remarkable job of commemorating the centenary with the establishment of Joel Stone Heritage Park, overlooking the Admiralty Islands.

Gananoque was actually attacked, and years ago this was commemorated in a historic plaque, “Raid on Gananoque,” that was erected in front of the Town Hall. According to the late historian William Hawke, an American contingent of 70 riflemen and 34 militiamen beat back a British and Canadian force of 110 men, destroyed the bridge over the Gananoque River and ransacked the home of the town’s founder, Col. Stone. A random shot by the invaders hit Mrs. Stone in the hip, causing lifelong lameness. One hundred and 40 years later, a veteran Gan observer delighted in telling how Mrs. Stone, as the Americans advanced, dropped the family’s gold possessions into a barrel of soap. “It was the first time,” he chortled, “that soft soap won over military aggression.”

So much for humour, but I still wanted to link something tangible and personal with 1812. Far from the Lake Ontario and St. Lawrence communities that bore the brunt of the U.S. attacks and threats of attacks, I remembered a “Eureka moment.” On a circle tour through the Kingston-Leeds region, I recalled seeing a small plaque citing a local man who had fought in the 1812 war and survived and flourished.

It was in the hallway of Stirling Lodge in the village of Newboro and on a return trip, a former Whig-Standard colleague, Dudley Hill, a member of the family that operates the historic Rideau resort, dug out details on the person cited in the plaque.

“At last,” I said to my People-person self, “here’s a direct link between today and yesteryear. Wars, both ancient and current, are won by firepower, leadership, courage, tenacity and tactical strategy, but mainly by the number and action of 'boots on the ground.'” Here was a man who was in those 1812 boots.

His modern-day citation, beautifully printed and framed, hung in the hallway of the lodge, built around the dining room of the 19th-century home of John Kilborn. He was born in Elizabethtown, near Brockville, and hadn’t reached his 20th birthday when the U.S.A. declared war on Canada.

“I volunteered to serve in the first flank, company of the County of Leeds … for six months’ service,” he wrote for a biographical chapter in the 1879 History of Leeds and Grenville. He was the first man placed on sentry, drilled daily, and participated in an unsuccessful raid on Ogdensburg. Moved to Johnson in early 1813, his company made another attack on the New York State town. It was regarded as successful despite “five or six killed” and 42 wounded.

After serving two months beyond his allotted time, he returned home to Brockville. When the Parliament of Upper Canada raised a Provincial Regiment, he was recruited and commissioned as an Ensign or junior officer and appointed a quartermaster. Assigned to York (Toronto), the Canadians were “perfectly drilled and disciplined,” until the invasion of Canada by a U.S. force. With luggage stored at Fort George (Niagara-on-the-Lake), the unit marched to Queenston and mustered with “a few broken detachments of regulars and a few Indians” and engaged the enemy in “a hotly contested battle” above Chippewa.

“Finding it hopeless, with this small force, either to capture or drive them back to Fort Erie, our forces were withdrawn, leaving numbers killed and wounded and the Americans masters of the field.”

Kilborn’s unit retraced their steps back to Queenston, destroyed anything useful to the enemy, approached Fort George, set up a piquet guard and raided a nearby orchard. After a daylight march to Niagara, they camped within range of the fort.

By July 25, 1814, his regiment reached Lundy’s Lane where, he said, “the greatest and most important battle of the war was fought.” His unit was formed into a light brigade and, aided by Indians and artillery, prepared to meet the advancing Americans. He suspected the enemy forces were trying to outflank their lines and get in the rear.

While extending their line he came directly on a company of Americans formed two deep, the front rank with bayonets charged and the next rank with arms presented ready to fire. “The officer at the head of the company demanded a surrender and after a short hesitation I told our men to throw down their muskets. Three or four attempted to escape and some were shot.”

His men were taken prisoner, then together with 18 officers and 50 men, were marched off to near Chippewa, put in a Durham boat under heavy guard and rowed across the Niagara River to a short distance above the falls. Tired and hungry, the men were fed and then marched off to Buffalo, loaded into covered wagons and taken on a six-day trip to Albany. Eighteen men then went on to Pittsfield, Mass., the headquarters for prisoners of war.

“We remained there for nine months until the news of peace being proclaimed, when we were discharged and offered to return home to Canada,” he wrote years later. The rank and file soldiers drew rations while the officers received a $20 monthly allowance and travel expenses home.

Kilborn took up a trade at Unionville, north of Brockville, and was employed in assisting emigrants who first settled in Perth in 1816. It was not without hard labour. “I forwarded all the families to the Bay (Portland) and had to cut a road the last three miles to reach the (Rideau) lake.” The rest of the trip was made by ox sleds and scow. The route was well-known to Kilborn, who had obtained the contract for transporting all stores and supplies.

Married at age 21 in June 1816, the union produced one daughter and eight sons, and 12 grandchildren and 18 great-grand children. He located to Kilmarnock on the Rideau Canal, was elected to the Parliament of Upper Canada, became a Justice of the Peace and an associate judge and postmaster at Brockville. He continued his military career, rose to the rank of Captain and was in command of a company of volunteers at Gananoque during the 1837 rebellion. He retired as a lieutenant-colonel - the only surviving officer of his regiment.

He retired to Newboro in 1876 and is saluted as “one of its most distinguished founders.” There is no known photograph of him and no historical plaque, but his name lives on at a unique store, “Kilborn’s” located next to the site of his Newboro home.

Finding his detailed biography filled my need for a personal contact with 1812 and wound up my odd odyssey, but still left me wanting a deeper perspective into the war. More answers were given at the conference held in Kingston in October… but I am sure there is more…

By Bill Fitsell

Bill Fitsell is a naval veteran and an amateur historian. A former People columnist for The Whig-Standard and author of four books, he usually focuses on a somewhat less-violent war on ice. He was the founding president of the Society for International Hockey Research and serves on the Board of Directors of the International Hockey Hall of Fame in Kingston, Ontario, Canada.

Bill has written four books: Hockey's Captains, Colonels and Kings (Boston Mills Press, 1987), Fitsell's Guide to the Old Ontario Strand: A Cultural and Historical Companion(with Michael Dawber, Quarry Press, 1994), Hockey's Hub: Three Centuries of Hockey in Kingston (with Mark Potter, Quarry Heritage Books, 2003) and How Hockey Happened (Quarry Press, 2007). In 2006, the Society for International Hockey Research presented him with the Brian McFarlane Award for outstanding research and writing.

______________________

A sample of historical references to the War of 1812