When I was young, one of my favorite verses went like this: "They who wait on the LORD Shall renew their strength; They shall mount up with wings like eagles, They shall run and not be weary, They shall walk and not faint" (Isaiah 40:31). The imagery of mounting up with strength like that of an eagle's wings captured my young mind and has stuck with me throughout my life. Because of the picture these lovely words painted for me as a child, seeing an eagle in the wild became a lifelong dream of mine. I would have never imagined back then how close to home the fulfillment of this dream would be.

I grew up spending most of my summers with my family on the River. Though I never spotted any eagles, the skies were constantly filled with plenty of other winged beauties to captivate my attention. In fact, when I saw my first osprey I mistakenly thought that it was an eagle. Apparently, I'm not the only one who has confused ospreys with eagles. There are definitely similarities between these two birds.

An Osprey Intervention

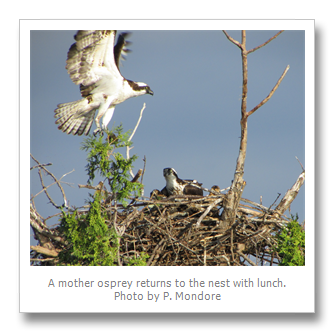

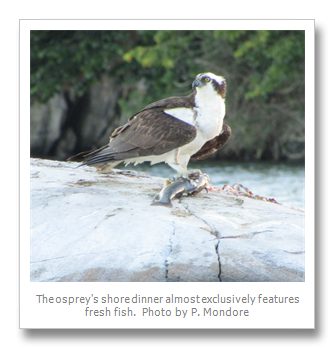

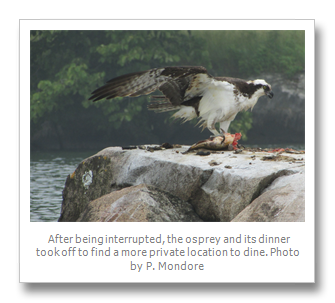

The osprey is a large raptor measuring approximately two feet tall with a five-foot wingspan. While they are sometimes confused with bald eagles, they can be identified by their white underparts and the distinctive black eye stripes on the side of their otherwise white head. Ospreys have large hooked talons which they effectively use for catching fish (their main diet). They are one of the few raptors that completely submerge themselves when diving for fish. Then, they will fly back to their nest with the fish pointing headfirst to ease wind resistance.

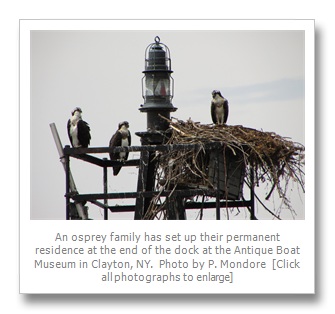

Ospreys build their nests (a pile of sticks lined with seaweed) in the tops of trees, utility poles or manmade platforms. The nests start out large but grow larger with every passing year since ospreys commonly return to the same nest. Spring cleaning involves adding more materials so nests have been known to grow up to 10 feet high weighing in at over a ton. Since their diet is almost exclusively fish, it is no surprise that osprey nests are found near the water. Today, it is not hard to find an inhabited osprey nest here on the River. But it wasn’t all that long ago when this was not the case. The NYSDEC currently lists the Osprey in the "Special Concern" category, but back in the late 1960s the osprey had become an endangered species.

The osprey's rapid decline was caused primarily by the use of the insecticide DDT. DDT began to collect in fish, which make up most of the osprey's diet. It weakened the bird's eggshells making the survival rate of the chicks much lower. An estimated 1,000 active nests in the 1940s between New York and Boston declined to about 150 nests in 1969. In 1971 New York State banned DDT and the rest of the country followed in 1972. Since then, ospreys have begun a slow but steady comeback. In 1983, the osprey was downgraded to "Threatened" from its 1976 listing as "Endangered", and in 1999 it was downgraded from "Threatened" to "Special Concern."

Another help to the reestablishment of ospreys is that they have increasingly been using manmade structures to nest on. The NYDEC reports that since 2001, 60% of the osprey nests in the North Country are found on power poles and cellular phone towers. We have seen others on such manmade locations as channel markers, lighthouses and even a castle roof. Conservationists have also erected some artificial nesting platforms for the ospreys to build on. And their efforts have most definitely paid off. Today, ospreys are thriving throughout the North Country. Their nests can be found on islands throughout, the Thousand Islands, including the tower at the entrance to the Antique Boat Museum. The ABM made sure, even during their annual boat show, that the nesting family was given its privacy.

Since spotting my first osprey, these majestic birds have become a common sight on the River thanks to the efforts of local conservationists. But I never forgot about my dream to see an eagle.

The Eagle Has Landed

Then, in 2008 I was surprised to see an article in the Thousand Islands Life by Kim Lunman called “Eagles in the Islands”. I read it with delight. Maybe my dream would come true after all. Sure enough, eagles had been spotted on an island near Ivy Lea. In fact, there were reports of three different eagle’s nests in the Thousand Islands area. Along with the nests came the hope that the bald eagle population here at the river was making a comeback. According to the article, there were as many as 400 eagles nesting between the Ottawa River and the Great Lakes in the early 1900s. But from 1937 to 1999 not a single nest could be found in the Thousand Islands area. That is what made these three sightings so exciting.

The Bald Eagle is found only in North America. This magnificent raptor was adopted as the symbol for the United States of America in 1782. It is one of the largest birds of prey in the world being up to 3.5 feet tall with a 7-foot wingspan and weighing up to 15 pounds. The female is usually larger than the male. Of course, the Bald Eagle isn’t really bald. The word "bald" originally meant "white-headed". Its scientific name, Haliaeetus leucocephalus, means "white-headed sea eagle" in Latin. As its name implies, both the male and female eagle have a distinctive white head and neck on its dark brown/black body. It also has a white tail mark. However, only the mature adults have these markings. From birth until they are about five years old, eaglets are almost solid brown. The young birds also have a dark beak and eyes, both of which will turn to bright yellow as they mature. Eagles can live up to 30 years in the wild.

Bald Eagles are also known for their excellent vision. They can see about seven times better than humans. An eagle can spot its prey from over three square miles away. They are also excellent fliers, being able to reach an altitude of 10,000 feet and achieving speeds of up to 35 mph.

In addition to occasionally being mistaken for ospreys, eagles share several other traits with their fellow raptors. Eagles make their nests, which are called "aeries", at the top of tall trees near large bodies of water. Like the ospreys, since they return to the same nest every year the nest continues to grow in size and weight, and can eventually become larger than the nest of any other bird in North America. The largest eagle’s nest on record measured 20 feet deep, 10 feet wide, and weighed two tons.

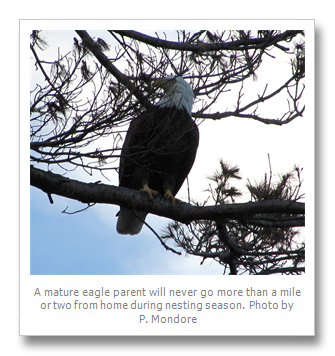

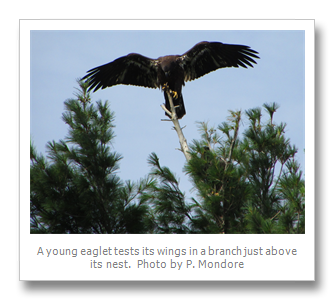

Also like the ospreys, bald eagles are believed to mate for life. A pair constructs an enormous stick nest—one of the world's biggest—high above the ground and tends to a pair of eggs each year. The newly hatched eaglets are covered with soft, grayish-white down. They are too weak to stand and their eyes are partially closed. They are totally dependent on the parents who watch over the nest together. The young birds grow rapidly adding a pound to their weight every four or five days. By three weeks they are a foot high and their feet and beaks are very nearly full size. Between four and five weeks, the down is replaced by black juvenile feathers. They can stand, and also can tear up their own food. By six weeks they are nearly as large as their parents. By eight weeks, the eaglets’ appetites are nearly insatiable keeping the parents busy almost around the clock trying to keep them fed. At the same time, the eaglets begin to try stretching their wings. Somewhere between week 10 and 13, the eaglets will take their first flight, though the parents will continue to feed them up until their first winter. From the time the parents build the nest until the young eagles are on their own takes about 20 weeks. Throughout that time period the parents will remain within one to two miles of the nest.

Ironically, even though it is the national symbol of the United States, the bald eagle nearly became extinct here. Much like the osprey, the bald eagle population was seriously threatened with the increased use of pesticides like DDT. Since DDT use was restricted in 1972 and through the aid of reintroduction programs, eagle numbers have rebounded significantly. Like the osprey, the eagle has become another wildlife success story having now been upgraded from "Endangered" to "Threatened" by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Though their numbers have increased in many areas, bald eagles remain most abundant in Alaska and Canada.

Wings over the River

I was excited to hear about the sightings on the River but absolutely delighted when I had my own personal sighting. We had heard there was a nest in our area and went out in the boat to see for ourselves. We found the nest but, alas, no eagles. As we pulled away I looked back one last time and spotted a single eagle at the top of a tree. In the coming days, we had the pleasure of seeing the mother eagle on her nest, and her two eaglets as they matured over the course of the summer months.

But we were not the only ones on the River who had spotted eagles. The Thousand Island Sun reported that at least two other nests had been spotted in different locations along the River. Someone submitted a picture of an adult eagle with a radio tracker on its back on an island near Goose Bay. Another reader sent in a picture of an eagle family that had successfully nested on Carleton Island. Readers were informed that the adults have been named George Washington and Betsy Ross, and their eaglets have been named Fife and Drum. I’m now thinking perhaps I should name my eagle family. Maybe next summer.

It appears that the 62-year absence of eagles’ nests in the Thousand Islands area has come to an end. Much like the ospreys, eagles are indeed making a dramatic comeback in the area. Both of these amazing creatures will hopefully soon become common sights here on the River. And that reminds me of another one of my favorite verses: "How precious is your steadfast love, O God! The children of mankind take refuge in the shadow of your wings...and you give them drink from the river of your delights" (Psalm 36:7, 8).

Our River is truly a river of delights, and it is even more delightful knowing that we are increasingly able to enjoy it under the majestic wings of ospreys and the bald eagles.

By Patty Mondore

Patty Mondore and her husband, Bob, are summer residents of the Thousand Islands. Patty is a published author and a singer/song writer. Her most recent books include River Reflections: A 90-Day Devotional for People Who Love the Water and its sequel, Nature Reflections: A 90-Day Devotional for People Who Love Nature. Her other books include River-Lations: Inspirational stories and photos from the Thousand Islands, A Good Paddling, Proclaim His Praise in the Islands, and Perennial Faith. She and Bob, co-authored Singer Castle, and Singer Castle Revisited published by Arcadia Publishing, and co-produced Dark Island’s Castle of Mysteries documentary DVD in addition to a Thousand Islands music DVD trilogy. Patty is a contributing writer for the Thousand Islands Sun. Her column, "River-Lations", appears in the Vacationer throughout the summer months. The Mondores are online at www.gold-mountain.com.