Editor’s Note:

Our TI Life policy suggests we stick to stories, photographs or illustrations that relate to the Thousand Islands – Above the River (Ian Coristine’s photographs); Beside the River, (22 communities on both sides of the River, but not very far inland… ) and under the River, (Diving Clubs…) So when we received Pauline Buckby’s article this month, I hesitated, but only for a minute.

Pauline writes about her part of the world, Tasmania - and while doing family genealogy, she discovered her husband’s ancestor, Chauncey Bugbee, came from Jefferson County and was sent to Tasmania in 1838, as a prisoner of war from Fort Henry in Kingston., ON in 1838. She discovered all of this through our Thousand Islands Life articles.

Pauline, like other Tasmanians are getting interested in the Thousand Islands and at the same time North Americans are getting more interested in that other island down under. So we are including this article as a geography lesson and we thank Pauline, very much.

Life on Robbins Island, Tasmania, AU.

A young American from Boise City, Oklahoma came to Australia for the 1956 Olympics in Melbourne, he fell in love with a Tasmanian girl and bought an island. This is the story of that island.

Robin Island is an island located off the northwest coast of Tasmania, separated by a highly tidal area, otherwise known as Robbins Passage. It is the seventh largest island of Tasmania, with an area of 38 sq miles,; is the largest freehold island in Tasmania and lies south to adjacent Walker Island. Over the years it has changed ownership and to this day remains privately owned. The island can be reached by boat, plane horse, vehicle or foot – all have their risks.

Tasmania is Australia’s 7th State, and the smallest, a mere speck on the globe, in size 26,215 square miles. Separated from the mainland by Bass Strait, a capricious stretch of water with strong ocean currents, set in the east, through comparatively narrow inlets, with currents flowing from the south. Add to this fierce westerly wind sweeping around the world from South America, with nothing to heed its progress for 20,000 miles and you have a dangerous stretch of water. The Strait has earned a local title of ‘Dire Straits’ due to the number of shipwrecks in the area.

Crossing Robbins Passage to the island has inherent dangers, the passage is quite unique in its way, and tide runs out from both sides – east and west – leaving two main channels. At high tide it is possible for fishing boats to sail through, as there is a rise and fall in tide of 10-12 feet; at low tide it is possible to drive across between the mainland and Robbins Island through fairly shallow water. However, the passage is capricious and easterly weather can prevent the tide going out in its entirety.

Rough weather is known to wash quite dangerous holes in the sections covered with water and if a vehicle is not kept moving it is likely to get bogged in the soft sand.

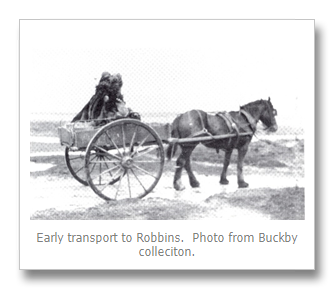

Until a public road was made in the early 1960s, to the beginning of the crossing, vehicles made their way across Buckby’s property at Illawong Plains and then drove along the beach to reach the only place possible to cross to the island.

Robbins Island was not a good place to live if you happened to be pregnant. Early in the year 1925 a woman was expecting her second child and was not anxious to have the birth on the island. When her birth was imminent, the only way to get to the mainland was by the crossing. Accompanied by friends they set off by horse and cart, they got as far as Buckby’s Point, on the island, when the baby was born on the back of the cart.

The party continued another four miles to the crossing and found the tide was coming in and, to make matters worse, they were half way into the first channel, when the cart got stuck. The horse was untied quickly and with one of the women carrying the baby above her head, they managed to make the mainland through chest heigth water. The woman was made comfortable on the beach while one of the men rode the horse for help. As luck would have it neither the woman nor the baby suffered any ill effects; the baby was named ‘Faith’ because the mother felt sure they would survive.

The distance from the mainland to Robbins Island, through the channels, is 1,24 miles; a notice now stands on the beach at the crossing;

Prior to European settlement, the first known humans to reside on Robbins Island, were the indigenous northwest tribe of aborigines known as Parperloihener. Tasmanian aborigines were a different race in both habit and customs, to those on the mainland of Australia.

Later came the whalers and the disintegration of the Aboriginal population. A whaling station was established on Robbins Island, but by 1825 the whalers had hunted-out most of the elephant seals and the station was abandoned.

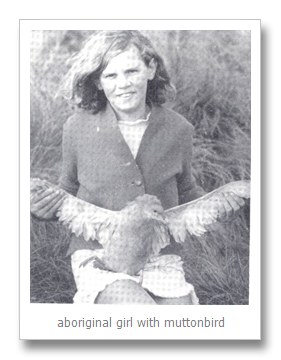

For a couple of months each year the Procellaridae, commonly known as the mutton bird, a group of one hundred sea birds share the island with residents. The bird belongs to the Petrel family of sea birds and is about the size of a small duck. It is described as having a tube-like nostril on top of its upper beak; this is hooked on the end to assist the bird to hold its prey; their main diet is krill, plankton and small anchovies. They are an ocean living bird and have difficulty moving about on land or taking flight in windless conditions. The bird1 has a wing span of three feet that enables them to fly at a speed of 80 mph. [1]

Approximately twenty three million Muttonbirds breed in about two hundred and fifty colonies, in southeastern Australia, from September to April and eighteen million of these arrive in Tasmania each year. Their colonies are usually found on headlands and islands covered with tussocks and succulent vegetation; the headlands allow for easy take-off and landing. Present day ornithologists refer to the birds as Short-tailed Shearwaters. Shearwater is an apt name for this ocean bird, describing its skimming flight, as it glides close to the sea in search of food.

Banded birds have been known to return to the same burrows for a period of thirty years. Arriving on the island, the adult birds clean out their burrows, then return to the sea for three weeks to feed, before the egg laying takes place from late November, to the first week of December; each female bird lays one large egg. Both male and female incubate the egg, taking alternate shifts, varying from ten to sixteen days at a sitting and during this period the sitting bird receives no food. [2]

The incubation period takes between 52-55 days and the chicks’ hatch between January 10th –23rd. The chicks are fed nightly for the first week and then the intervals grow longer, until young chicks are finally left to fend for themselves. Early April these young chicks come out of their nests looking for food, they are covered with dark, soft down and are fat and full of oil.

The young birds leave the island and stay at sea until they are three to four years old without returning to land. Breeding age for the female bird is five years, they mate a year later and stay together for their life span. Muttonbirds3 are known to live to at least thirty-six years of age and expectancy can to extend to forty.

The Muttonbird is the basis of one of Australia’s oldest primary industries and was first used by the early settlers; the birds are harvested in March each year and the season is open for five weeks. Nothing of the bird is wasted, their oil is used extensively by horse owners, as a food supplement for their animals; the feathers go to factories and are used in quilts and sleeping bags; the bird itself is frozen, canned, or salted for the food markets

Many thousands of words have been written about this fascinating bird which leave their young when just a few weeks old, to make their own way all the way back to the feeding grounds. The young birds do not feed on their long flight north to the Bering Sea; for this reason they must be in good condition when they leave the nesting grounds; they must rely on fuel stored in their bodies in the way of oil.

While all this activity is going on, cattle graze quietly on the island and breed their calves. They graze naturally on lush pastures, without supplements or hormones, while breathing the cleanest air in the world: air has been tested and recorded at Woolnorth on the far north-western tip of Tasmania.

Cattle droving was feared to be a dying art in Tasmania, but at the start of each year, the tradition is kept alive with the Robbins Island saltwater cattle muster.

It takes about three hours to walk cattle from the stockyards, around the southern shoreline of the island, to the crossing. During the annual muster, bands of horsemen swim the cattle through saltwater channels at low tide to move them peacefully between grazing areas.

The island was used to graze sheep, primarily for wool production, before the 1850s. In 1961 an American, the late Gene Hammond bought the island; it has remained in his family and today, two of his three sons run the island. Currently they produce full-blood wagyu beef which is exported to Japan. John and Keith Hammond have run wagyu cattle since the early 1990s.

The cool climate, salt air, and pristine environment are ideal for naturally raising some of the most tender and best tasting beef4 in the world.

There is a certain magic about Robbins Island, a peace and tranquility that is hard to find in the world today. There are beautiful ocean beaches, extensive sandbanks and groups of beautiful trees. The crossing can still create drama, but it is something that is part of its fascination.

By Pauline Buckby

Pauline Buckby, although travelled extensively overseas, has lived most of her life in Tasmania. She is 91 years of age and just published her eighth book on Tasmanian history – and is now writing number nine! Pauline became interested in writing when she moved to Circular Head in 1960, saying, “Writing became a hobby to overcome loneliness of country life after living most of my life in the city.” Pauline has written a number of published short stories and articles; holds three writing diplomas, and she also won a National Literary Award for her second book, ’Robbins Island Saga’. She is Past President of the Fellowship of Writers and has always been interested in Tasmanian History.

2

Dr.D.Seventy – C.S.I.R.O Division of Wildlife Research