Patriot Chronicles: Nathan Williams, A Rebel who Escaped

Written by John C. Carter posted on November 13, 2014 12:26

Patriot Chronicles: Nathan Williams, a Rebel Who Participated In and Escaped From the Battle of the Windmill, is presented by John Carter as part of a series on the 1838 Upper Canadian Rebellion.

Introduction

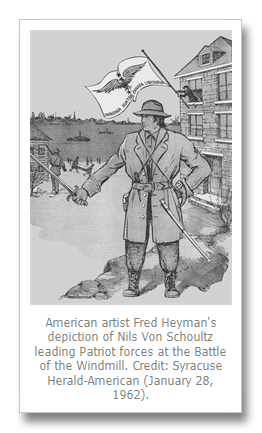

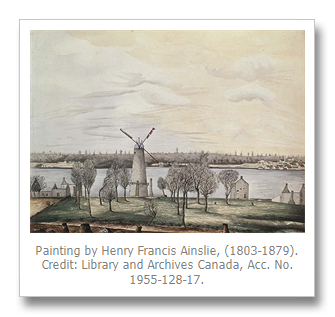

November 12-16, 2014 marks the 176th anniversary of the Battle of the Windmill. Much has been written about this important incursion (the second last skirmish of the 1838 Upper Canadian Rebellion), its participants, and aftermath (see list of suggested readings in the November 2013 issue of TILife). We know about many details of that engagement, those killed, captured, incarcerated, and those transported as political prisoners to Van Diemen’s Land. This article is about a rebel who participated in and then escaped from the battle, but of whom little is known, in the historic annals of the Patriot Wars.

Nathan Williams is an enigma. It is unclear where and when he was born. It is possible that he resided in Oswego, New York prior to the Battle of the Windmill. It is known that he escaped on November 16, 1838. He is not recorded in the appendix of participants provided by Daniel Heustis. Perhaps he enlisted under a pseudonym, or was not named by Heustis because he was not captured, injured or killed? He was however one of the 5 to 7 men who apparently were able to make their way back to New York State, defying the odds by not being captured, incarcerated or losing their lives. Nathan Williams was one of the few escapees who wrote about their experiences. His recollections were published in two period articles which appear below in their entirety.

The Battle

The initial description entitled “The Prescott Expedition,” was written on December 1, 1838. It probably first appeared in local New York papers. The following account was re-published in the January 3, 1839 edition of the Watertown Jeffersonian, taken from an earlier issue of the Oswego Palladium:

| |

|

“Mr. Carpenter, - Being aware that many false reports have been circulated and credited in regard to the Prescott expedition, and feeling that facts alone are desirable, it is with a melancholy pleasure that I now forward for publication, a brief account of the unfortunate adventure. Being an eye witness and a participant of the whole scene from the time of our landing, till the time of our surrender, I shall confine myself to such statements as far as possible, as from my own observations I know to be correct. For history of the expedition previous to the time of our landing, I will refer the readers to an anonymous article published in the [Albany] Argus bearing date Nov. 14, (and which was copied into the Palladium of Nov. 29.) as this with a few exceptions is a true history of the affair. On Monday the 12th inst., we succeeded in landing one of the schooners and 100 men under the command of the gallant Col. [Nils] Von Shoultz [sic]. During the afternoon several of our men, together with myself, effected a landing in small boats from the United States steam boat. Several also took passage in small boats and came over during the night, making in all a force of about 150 men on the following morning.

About 6 o’clock, A.M., on the 13th, we were apprised of the approach of the British, and commenced our preparations to receive them. From what we could discover it seemed to be their intention to make a simultaneous attack upon us both by land and water. In this conjuncture we found we were not mistaken, and in a short time the steam boat Experiment, bearing 2 guns, bore down upon us and commenced a heavy fire, while we were about the same time attacked by a force of about 300 men on land; consisting of regulars, dragoons and militia – the Experiment taking the lead in the engagement.

Our first order was to man two of our cannons and bring them to bear upon the enemy on the boat. Consequently two of our cannon were stationed upon the bank of the river, one under the command of Col. Von Shoultz [sic], the other I think under the command of Capt. [Christopher] Buckley. Scarcely had the cannonading commenced before a heavy firing of small arms was heard at the distance of about 200 rods on land. No sooner had the report of small arms been heard (which at first took place between the enemy and our own guard) that the main body of our men repaired to the field, when the discharge of small arms became almost an incessant roar. The scene, although melancholy, was at this time one of the most sublime and imposing character. The same incessant discharge of musketry was to be heard in almost every direction, the cannon sent forth its frequent and monotonous sounds, whilst the groans of the dying, together with the anxious expressions of the slain, added to the sublimity of the scene. Acting as I did in the capacity of fireman at the cannon, my attention in the commencement of the engagement was not so much confined to the prospect in the field.

The cannoning between the guns on the river and our guns was maintained about half an hour. At this time the boat had received several effectual shots from our guns, and being no longer able to sustain herself, withdrew from the engagement. Our order was then to repair to the mill, and maintain the action from the windows, as many of the British had approached within musket range. For some time our men sustained themselves with the utmost bravery, till at length, by the increasing number of British, they were compelled to fall back and maintain the action under the protection of the walls and buildings near the mill. For some time the contest was sustained without the slightest prospect of retreat on the part of the British; but to them our fire had become so destructive, whilst their own was attended with little effect upon us, that as a matter of expediency, they were at length forced to abandon the contest. From the commencement till the close of the engagement, I am informed by Dr. Sherman of Ogdensburgh, it was three hours. My own opinion would teach me considerable less, though I had no time piece to determine. Relying upon the most authentic accounts and appearances upon the field, it cannot be said that the British had less than fifty or more than 100 killed and about 100 wounded. Our own loss was 5 killed, 13 wounded and several taken prisoners.

On the 15th, the day following, nothing of much importance transpired, save the capture of five men who had been sent on an express to our friends at Ogdensburgh, three of whom it was said were shot before they were overtaken by the steam boats which were in pursuit of them. At an early hour on the 15th inst. we were ordered to man one of the cannon and attempt dislodgement of the enemy, who had been concealed in a house the night previous, at the distance of about half a mile from the mill. Being rather an unusual hour for the reception of our guests, it seems we were not expected until we had taken our cannon with about twenty rods of the enemy and greeted them with a discharge of our gun; it being well loaded with canister shot. Penetrating the window, it had the effect of evacuating the house of about twenty armed men, who on their retreat were fired upon, and five of them left dead upon the field. During the day much firing was heard at a distance, but without any injury to ourselves; and whether our shot were returned with any effect upon the British is uncertain. During the evening the citizens on this side finding that a reinforcement was expected by the British, together with heavy ordinance, the day following, made the communication to us and forwarded a boat for our removal. Finding that our friends had deserted us, and feeling unable to sustain ourselves against such an event we were ordered to prepare ourselves for a removal; but before the necessary preparations were made, the firing of the British was heard; and supposing the British approaching us, the crew on board became anxious for their own safety and withdrew. Soon after, the Experiment settled down upon us and prevented any further attempt for our removal.

About 3 o’clock on Friday, the 16th, we discovered 2 large Steam boats making down the river, loaded with men, and as we supposed, with heavy artillery. After calling a short time at Prescott to make the necessary preparations, they again set sail, and after casting anchor about one hundred rods below the mill, commenced a brisk cannonading upon the mill, besides the other buildings which were in our possession. Two cannons had also been stationed in front, which were brought to bear upon us, to the no small injury of our buildings. Finding that we could not sustain ourselves, our men became alarmed; and in expectation of more humane treatment, should they evade any further engagement, many of our most valiant men, some of whom were leaders, actually refused another engagement, and urged the propriety of an unconditional surrender. Consequently no encounter was given them on the day of the capture. About sunset, after repeated solicitations Colonel_____, who commanded at the mill, gave orders to lay down our arms and march out, and surrender ourselves as prisoners of war. Having marched out and called for quarters, the cannonading partially ceased, when the force on land marched down within about twenty rods of us, and commenced an inhumane attack upon us. Discovering no disposition to receive us as prisoners, and seven of our men already wounded, our orders were to retreat into the mill to await the painful destiny which soon must come upon us. Being within about ten rods of us at this time, a constant firing of small arms was directed towards our buildings, but with little effect upon us. Again our flag was presented, which was accepted, and again our men marched out, and surrendered unconditionally to the British. Our loss at this time, as near as can be determined, was 8 men killed, and near one hundred taken prisoners.

Such is a brief account of the unfortunate Prescott enterprise, which for gallantry of its participants notwithstanding its final issue, admits scarcely of a parallel in the whole history of the world.

In the course of the week, according to your request, I propose to communicate a narrative of my escape.

Yours truly,

NATHAN WILLIAMS ”

|

|

The Escape

The promised second installment of Williams’ recollections was published in the February 8, 1839 volume of the Toronto Mirror:

| |

|

“Mr. Dickinson: - After considerable delay occasioned by ill health, I embrace the opportunity of communicating to the public the particulars of my escape from Wind Mill Point on the evening of the 16th November last. In the Narrative of the Expedition I had occasion to observe that about sunset we were ordered to lay down our arms and march out and surrender ourselves to the enemy. But contrary to our expectations, even this unhappy alternative was not granted us. No sooner had we marched out and called for quarters then a brisk fire was opened upon us, and several of our men severely wounded. Being then ordered to retreat into the Mill, our men readily acquiesced with the exception of four or five of us, among whom were James L. Snow [Hastings, N.Y.], Chas. S. Brown [Brownville, N.Y.], and myself, besides two others whose names I do not know.

Instead of again retreating into the mill we repaired to a stone house, which was nearer and afforded a more immediate asylum than the Mill. The main body of the enemy had know marched down within 5 rods of us, and, as we supposed, would soon assail our building and make us indiscriminate subjects of an inhumane massacre. Our situation at this time was emphatically a critical one. Between an undisputed submission to such a fate and a resolute defence of ourselves, we, in the ultimate, saw little or no difference. However, we soon resolved upon the latter, and then our lives, if thus taken, should be at the price of blood. Having a pair of pistols I presented them to my companion and seized a musket myself; we stationed ourselves at the door prepared to meet our unhappy fate. But contrary to our anticipations we were not molested, but were left to the entire control of the house. Having waited about the space of half an hour, whilst in the meantime the attention of the enemy was directed to the mill, I suggested to my companions the propriety of leaving the house and retreating to the bank of the river where we might secrete ourselves in a pine grove which was situated in the rear of the mill. Accordingly we abandoned our first position and concealed ourselves as well as possible in the grove, about six rods from the main body of our men.

About 6 o’clock P.M. our men were taken prisoners and our buildings with the exception of the Mill set on fire. A search was then made in the grove for any one who might thus far have escaped. To the discharge of this task several of the militia were appointed who with their lights commenced a vigilant search in the vicinity of our concealment. Having approached within two rods of us, I beckoned to my companions, J.L. Snow and C.S. Brown, to follow me. My desire was then to pass up the river about half a mile, get beyond the main body of the enemy, and cross the road at that point. We had not proceeded far before I recognized my companions some distance in the rear, apparently making little effort to follow me; having no time to lose I did not return to urge them on, but hastened onward as fast as possible. I resolved to try the advantage of stratagem. I then resolved to ascend the bank of the river, gain possession of the road and feign journeying to Prescott – but no sooner had I gained possession of the road than I was discovered by the sentinel in the rear and bid to stop. However of this I took no notice but travelled on as though nothing had happened till accosted the second time, attended with a threat if I did not stop ‘he would shoot me down.’ Having now got the distance of several rods from the sentinel and having a better opportunity to cross the road and fields, I resolved to make the best of the opportunity which presented. Accordingly I started at the height of my speed, being fired upon by the sentinel and given chase by 3 of the militia, who also discharged their fusils, though without any effect upon me.

The pursuit was continued about forty rods and ended only by a precipitation of myself into a ‘mud-hole,’ which I did not discover till it had been encountered. Knowing that my pursuers were near, I resolved to remain in this situation a few minutes and await the result. As I hoped, my followers came up and without stopping or paying me any attention, like the ancient High Priest, ‘passed by on the other side.’ After passing the distance of a few rods I recovered myself, retraced my steps a short distance, and then repaired to the fields, leaving my pursuers to follow a different direction. Consequently I sought a direction directly from the river and into the country more remote from the Patriot excitement. Having gained the fields I continued my journey through the most unfrequented part of the country till I had travelled several miles from the river. Feeling a good deal fatigued I repaired to a small barn, where I purposed to remain thro’ the night and subsequent day; but from the intense coldness of the night I was obliged to abandon the idea and proceed on my journey. My intention was at this time to gain the river, and if possible to cross to the American shore; but on approaching the river my previous conjectures were confirmed by the discovery of a guard upon the river, which rendered any attempt to cross at that time imprudent. I then retraced my steps into the country, hardly knowing whether to remain in the forest or repair to some dwelling and call for entertainment. However, on discovering a house at some distance in the field, I resolved to repair to it and seek protection; accordingly I approached the romantic spot and after rapping at the door gained admission. Although the characteristics of extreme poverty were everywhere to be recognized, yet the kindness and hospitality with which I was entertained contributed more to the happiness of my situation than all the luxuries of affluence & wealth.

To my friend and benefactor riches were a stranger, yet the frank, open, and expressive features of his countenance plainly indicated that he was neither a stranger to happiness or the more exalted feelings of our nature. To such a person had Providence directed me for protection. And to him I made known my situation, whilst his every feature bespoke an anxiety for my welfare as I rehearsed my adventurous tale. The wife was engaged at the same time in preparing what little their scanty means afforded for my supper. However, it was enough, although their kindness was wont to bestow a more palatable meal, but it was the best their circumstances afforded, and with this I was conducted to the chamber where a pallet of straw was prepared for my acceptance, on which I couched for the remainder of the night. Having remained in this situation through the night and subsequent day, I was advised about eleven o’clock P.M. to continue my journey to the river, obtain a boat, and escape to the American shore.

After receiving the watch word which was required by the guard, I proceeded to the river in accordance with the advice of my benefactor. On reaching the river I commenced a search for a boat, but here I found my ingenuity again brought to a test as the inhabitants had taken the precaution of withdrawing them from the river. But committing my case to the care of Providence, I resolved to risk myself upon the strength of means within my reach. After considerable search, for the want of more suitable materials I was compelled to make use of some rails which I placed on the river, of which I constructed a raft on which by assistance of a stake for a paddle I affected a landing on the American shore after a pleasant voyage of about two hours. A shrewd friend has since remarked that the most despicable thing in the whole affair was the smuggling of a few rails from the Canada side over to the American shore; but taking the first cost into consideration, the expense of importation, &c., I can assure him that I have not yet had reason to lament the undertaking.

I cannot in justice to my own feelings and to true merit close this narrative without mentioning in particular the names of a few among the many who on my return bestowed upon me every attention which my situation demanded. Having lost my trunk and clothing through the kindness of Dr. Sherman of Ogdensburgh. To Mr. King and Mr. Daniels of the same place I must return my sincere thanks, as well as several others whose names I must omit. The name of Dr. Dewey, Mr. Pratt and Mr. Fletcher of Antwerp, Mr. Simons and Turner of Watertown, and Capt. Waugh of Sacket’s Harbor I have reasons to remember with sentiments of esteem and lasting gratitude. Such, kind reader, is the hasty account of my escape from a place and scenes which will ever be remembered with the most painful regret.

Yours truly,

N. Williams.”

|

|

Conclusion

Precious little is known about Nathan Williams after his involvement at and escape from the Battle of the Windmill. A man with the same name was elected in September of 1838, as Vice-President of a provisional republican government for Canada, at a Hunters’ Lodge convention in Cleveland, Ohio. It is unlikely that they were the same person. Nathan Williams recorded his recollections of the Battle of the Windmill and his escape, and then disappeared into oblivion, much like many of the participants in the 1838 Upper Canada Rebellion! However, we can thank him for recording and publishing his personal remembrances of the Battle of the Windmill, as we again celebrate the anniversary of this important historical event.

Dr. John C. Carter

Dr. John C. Carter is a Research Associate in the History and Classics Programme, University of Tasmania. This is his ninth article written for TI Life (Click here to view his other articles). In particular his February 2013 Patriot Chronicles: The Hickory Island Incursion and April 2013 The Burning of the “Sir Robert Peel”… set the scene for this important period of history. He can be contacted at drjohncarter@bell.net.

In addition, Dr. Carter has provided a bibliography to study this important era of Thousand Islands history which can be found in THE PLACE, History page.

Please feel free to leave comments about this article using the form below. Comments are moderated and we do not accept comments that contain links. As per our privacy policy, your email address will not be shared and is inaccessible even to us. For general comments, please email the editor.

Comments

Comment by: Ian Coristine ( )

Left at: 10:20 PM Saturday, December 6, 2014

When Paul Malo founded TI Life, he had several intentions, the primary one being "to build a greater appreciation for the place." We both perceived that because of circumstances (WW I, the Depression & WW II), that this place was no longer being seen in the same light as it once had been. Paul believed that it would be a positive thing if residents were exposed, not only of all that is happening here currently, but more importantly, what has gone on here in the past. This is precisely the reason why he wrote a trilogy of books about the Thousand Islands' Gilded Age, and via TI Life, he hoped also to share more of its earlier history, precisely as John Carter is doing here. So on Paul's behalf, a sincere thank you John for the effort you've put into sharing this and other important historical events.

|