I found a treasure! Not gold coins or rare gems. It was a thin book wearing a dingy blue cloth cover with embossed gold letters on the spine: The Thousand Islands of the St. Lawrence River. It was written by Captain Henry S. Johnston in 1937. So it wasn’t as ancient as it looked, but stuffed within its 142 pages were wondrous revelations about the river of a bygone era.

Most interesting to me were a couple of pages tucked into the chapter on William (Bill) Johnston. From the outset, I want you to know that the author, Henry S. Johnston, and the legendary William Johnston were not related. At least Henry didn’t think so. He wrote: Now I presume some of my readers are wondering if we were related? No, not as we know of. Both the Johnston families lived in Clayton and were neighbors living within a block of each other.

In the summer of 1879, when Henry was 17, his mother’s brother, Uncle John, came to visit. John Oades had lived in Clayton at one time and worked as a ship-builder, building steamboats and sailing vessels for Merrick, Fowler and Esselstyne. It was during that time between 1840 and 1852 that John was a good friend of Bill Johnston.

Now before I go further with the story, I need to make sure you, the reader, know who Bill Johnston was. Today, he’s sort of a folk hero and the inspiration behind Pirate Days, in Alexandria Bay. According to Henry’s uncle: “Bill Johnston was not a bad sort of a man at all but on a par with the average citizen. All sorts of stories and legends grew up and were enlarged upon at each recital until his memory to some made him a regular pirate and to others a hero.”

Hero or pirate, in 1838 Bill Johnston was a wanted man because of his involvement with the burning of the Sir Robert Peel, a Canadian steamship. Rewards were offered by both Canada and the State of New York. With help from his daughter, Kate, Bill was able to elude authorities for months, due to his intimate knowledge of the Islands. Eventually, he gave himself up, was imprisoned, escaped, pardoned and eventually became the first lighthouse keeper of the Rock Island Lighthouse.

In the summer of 1879—43 years after Bill Johnston went into hiding—Henry’s good friend, John Oades went out in a skiff to show his nephew the hiding places of Bill Johnston. Now I’ve heard about various hiding places through the years. One was Devil’s Oven near Alexandria Bay and another was Fort Wallace, a Canadian island near New York’s Canoe Point State Park. I read with great interest Henry Johnston’s detailed descriptions of Bill Johnston’s supposed hiding places and decided I had to see them for myself. So on a sunny, calm, warm September afternoon in 2014—176 years after Bill Johnston went on the lamb—my husband, Gary, and I set out in our small whaler, kayak in tow, to explore the hiding places of a pirate.

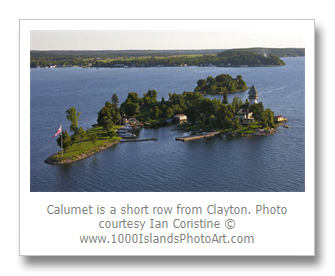

First stop, Powder Horn Island. We know it today as Calumet Island, which is located directly across from Clayton, NY. In the mid-1800s, it was called Powder Horn Island. When Charles Emery purchased the island in 1882, he preferred to call it by its original name, Calumet, an Algonquin word meaning ceremonial pipe. As we approached in our whaler, I read from Henry’s book:

Calumet Island was then in a wild state, and other than its general shape would not now be recognized. Where the castle now stands, it was similar to the head or upper end of Governor’s Island, a steep bank of boulders, and the lower end or on the stem part of Calumet it as only half a s wide as it is now, but was 8 to 10 feet high, all of boulder formation.

I looked up at the island. I was seeing something totally different than Henry was describing the island looked like in 1937. The castle is gone and only remnants of the foundation remain. Today, Calumet looks manicured and draped with velvet lawns. It’s hard to envision a wild and wooly spot. I already knew from reading Henry’s account that even he didn’t see anything in 1879 as the island had already changed so much since Bill Johnston’s time. I read the section aloud as we passed:

In the center of the stem running crosswise was a low sort of ditch or small ravine overgrown with vines and alders and other vegetation. One could pull a skiff easily from one side to the other as it was only about 60 feet across then. That was where his daughter left most of his food or any other things he might require. One would have a fine view up and down the river for miles either way. The pipe stem part of Calumet island had a wall built out into the river up to one’s waist and that part of island graded down at least 5 feet and the trees also lowered so it is now twice as wide there as it was when in its wild state.

When I was finished reading, I realized we were probably on the wrong side—the Clayton side—of Calumet. But no matter, the area he talked about had been modified to become a small harbor. I assumed the small ravine he described is where the marina is now. Calumet is a short row from Clayton and the cut would be on the side away from Clayton, facing Grindstone. It made sense that this would be a great place for Kate to hide food and supplies for her father to pick up later.

Next, we headed to the second hiding spot described by Henry, Whiskey Island. We started up the channel into the prevailing southwest wind until we reached the channel marker. We turned in, picking our way carefully around the shoals. At this time of the year, they were sticking out of the water like jagged teeth. Cormorants helped identify the shoals that were just under the surface They would stand atop, holding out their wings as if to say don’t come this way.

Gary turned north going between Whiskey and Papoose as I read the next section of Henry’s tale:

Next we stopped at the foot of Whiskey Island only a few rods from Grindstone. On the extreme northeast end of Whiskey Island, which is 8 to 12 feet high, there is a small drop, ravine sort, 10 to 15 feet wide, and sloping down to near the water’s edge perhaps 30 feet long. It was crossed by several old logs on which brush and growing vines hid all signs of an entrance, but one could pull a small boat of skiff size entirely out of sight with ease.

I was breathless with anticipation as we pulled around the northeast tip of Whiskey… and immediately disappointed to see that a huge boathouse now stood at that corner of the island. On top of that, we were looking against the sun. We could see a rock outcrop sort of, which was missing all the growing vines. I continued to read from the book:

Whiskey Island is perhaps three or four hundred feet long by 150 to 200 feet wide, elevated 8 to 15 feet, all granite formation just a few rods on the American side of the boundary. One has an unobstructed view up the Canadian channel for 18 miles and on the American, up the river about ten miles and down the American channel 6 or 7 miles. Just over the boundary line a half mile is Hickory Island. There were no cottages on the island in those days, but all the islands were wooded heavily by second growth. Whiskey Island was an ideal place for a hideout. A short swim of a couple hundred feet and you were on Grindstone Island, five miles long, two to three miles wide and with a few families living there.

We lingered in the water and I could see that Whiskey Island would make a wonderful hideout. Later doing more research online I found this wonderful aerial tour of the island which gave me a better idea of where Bill’s hiding place might have been: http://whiskeyislandlodge.com/Whiskey%20Island%20Lodge-Take%20a%20Tour.htm

From there, we motored around the head of Grindstone. We have been through the Lake Fleet Islands many times, but only around this part of Grindstone Island a few times. Lots of rocks and shoals and since it was late in the season and the water was low, we were on high alert in unfamiliar waters.

We were looking for Thurso Bay. The chart we had did not have the bays labeled and I thought it was the larger of the two bays, the one behind Jolly and Mead. It was quite shallow and the further we ventured inland the more it seemed it was not really a bay at all but a marsh filled with cattails.

I squinted into the late afternoon sun and wondered if we were in the right spot:

We rowed on around the north side to a large bay which is directly on a beeline between Clayton and Gananoque…now on the upper side well in the bay was a very nearly perpendicular ledge of granite, mostly covered with thick cedar trees and vines which grew to near the water and overhung a nice ledge just above the water, a nice place to haul out a small boat being entirely hidden from sight. Another hideout of Bill’s; one could leave his boat, walk across the head of Grindstone Island a couple of miles, doff clothes and swim over to Whiskey Island if need be. This bay is known as Thurso Bay. The Bluff of granite was the Forsyth granite quarries, now abandoned.

Later while doing more research I came across a map that had Thurso Bay on it. If the smaller bay to the west was Thurso Bay then what was the large cattail bay we found? I emailed a couple of friends who, in turn, passed my inquiry along to other area residents, which started quite a lovely debate as to what the name of the bay is that we stumbled into. Some thought it was Long Bay or Long March while others insisted it was Thurso Bay. All this debate only solidified in my head how easy it must have been for Bill Johnston to hide here.

From the marshy bay behind Mead, we continued on to Fort Wallace, an eighth of a mile across the US/Canada border in Canadian waters. Here’s what Henry says about Fort Wallace:

Fort Wallace [is] another look out of Bill’s, who named the island himself, the boundary line being midway between the island and Grindstone. It is a small island a couple of hundred feet long, 14 or 20 feet above the water and has an excellent view up and down the Canadian channel.

We went completely around Fort Wallace and I noted its proximity to Canoe Point. I imagined Bill Johnston climbing to the top and looking carefully both ways to see if anyone was coming up or down river before getting into his skiff and rowing back to Grindstone.

This was the last place on our list of Bill Johnston hideouts and I realized I hadn’t really seen any of his actual hideouts. Still, with Henry’s great descriptions, I could imagine the pirate who once roamed these waters. Perhaps someday, I’ll explore Thurso Bay, but I’ll have to find out who owns the property. A task for another season, another year, part of the never-ending adventure of history and life in the Thousand Islands.

By Lynn E. McElfresh

Lynn McElfresh is a regular contributor to TI Life, writing stories dealing with her favorite Grenell Island and island life. You can see Lynn’s 70+ articles here – as she helps us move pianos, fix the plumbing and walk with nature. During summer 2014, Lynn researched a number of new topics that she is sharing throughout the winter… Enjoy.

Editor’s Note: A fascinating discovery project for our Lynn McElfresh. We have included several articles in TI Life about our Pirate Bill Johnston, written by Shawn McLaughlin. (Click here to see articles Published in January, February and September 2012 ). In addition, this editor discovered these illustrations in our Canadian Library and Archives, in Ottawa. They were drawn by Brockville artist, William Denny, 1804-1886. To Lynn, Shawn and others… please keep on looking!

|

Click to Enlarge all Photographs

| | |