Written by

Robert L. Matthews posted on February 13, 2015 12:30

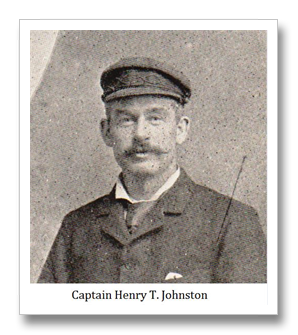

Last summer I read Captain Henry Johnston’s 1937 book, The Thousand Islands of the St Lawrence River with Descriptions of the Scenery, and Historical Quotations of Events, and Reminiscences, with which they are associated. It was an account of a tour boat’s trip through the islands describing sights along the way.

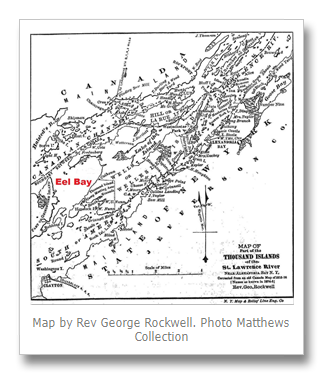

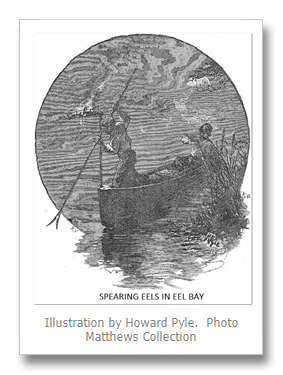

The book was interesting as it gave an excellent description of the Thousand Islands’ area during the thirties. Halfway through the book, Johnston wrote “We are now in Eel Bay.” He described the bay in detail mentioning that the water’s depth varied between three and ten feet with a muddy bottom. Native Americans [must be politically correct] speared eels there during the months of June and September when eels “swarmed” the bay. The eels were then cured much in the same manner as venison was cured and saved to be eaten later in the winter. Interesting, but Johnston was not yet finished. All kinds of game fish are native to The River and I just assumed the same was true with eels. Not so! Johnston wrote that the eel is a foreigner to The River.

Johnston had my interest! He went on to say that eels were born in the Atlantic Ocean off the coast of Spain in the vicinity of the Azores Islands. From there they migrate to our fresh water streams and rivers where they spend the rest of their lives until the call of nature stir them to return to the place where they were born. There they would spawn the next generation of eels. It was the first time I had heard such a tale.

It was hard to believe that eels would travel thousands of miles across the Atlantic Ocean, swim up the St. Lawrence River to live in Eel Bay. Why Eel Bay? Apparently it’s a combination of factors. The water’s depth is about right and eels like to burrow in the muddy bottom with just their heads showing so they can grab an occasional morsel of food as it swims by. They particularly like The River’s young game fish. Suspecting this might be a fish story, I decide to do some more research.

Since I had access to the book; State of New York Forest, Fish and Game Report of 1907, I started there. The book claimed eels sometimes exceeded four feet in length although two feet was the norm and female eels were larger than male eels. The book related how millions of young eels were known to ascend streams and rivers during the spring but small eels were seldom seen in the fall. Eels were described as voracious, powerful swimmers committing havoc at night by attacking whatever lives in their habitat. The article admitted that their breeding habits were still a mystery. Since the book was written over one hundred years ago, more current information was needed, so it was on to the Internet.

I learned that eels do not breed in fresh water; ever! Exactly where the female eel goes to spawn is not known as ripe [pregnant] females are rarely, if ever, seen. Eels drop completely out of sight once they leave the shore and enter the Atlantic Ocean. After the female eel deposits her millions of eggs, the eggs float in the upper levels of the ocean until they hatch. The resulting larva’s appearance is completely different from the look of an adult eel as they are ribbon like and perfectly transparent. Eventually the larva yields small eels who find their way to fresh water streams and rivers along the east coast. Like the Pacific salmon, eels usually find their way past obstacles such as dams, locks and waterfalls to reach their new home.

While eels have been studied for centuries, their life history still remains an enigma. Remember the earlier passage describing young eels ascending waterfalls in the spring but not seen in the fall? That now makes sense as only adult eels are seen headed to the ocean. Young eels that ascended The River in the spring are enjoying life; growing up in Eel Bay [and elsewhere] waiting for nature to give them the sign to return to the ocean to procreate. That wait could be as long as twenty years.

An additional mystery is that while both female and male eels appear in equal numbers at the mouth of the St. Lawrence River in the spring, only the females are found in the Great Lakes and the St. Lawrence River. What happens to the male eels is unknown. No wonder eels only spawn in salt water.

The American eel is on the verge of becoming an endangered species. Last year [2013] roughly 40,000 eels migrated up the St. Lawrence River compared to about 1,000,000 some ten years earlier. Thankfully studies are being conducted by both Americans and Canadians to address the problem.

My research essentially confirmed Captain Johnston’s account of eels in Eel Bay. I was impressed. If you’re fortunate enough to find a copy of his book, it’s a worthwhile read, not just the paragraph or two on eels, but for Johnston’s knowledge of Thousand Island history.

Note: The author, Captain Henry T. Johnston, was born 1863 in Clayton. At the age of twenty he earned his pilot’s license and began life on The River. He sailed the steam yacht “Sirius” for five seasons; the “Alert” for two seasons and later served as Captain aboard the steamer “Nightingale” ferrying passengers between Clayton and Thousand Island Park. Some readers may be curious about the Johnston House in Clayton on Riverside Drive. It was Captain Henry Johnston’s father, Captain Simon Johnston, who owned the house. The father had the house built in the early 1880s and lived there until his death some ten years later. |