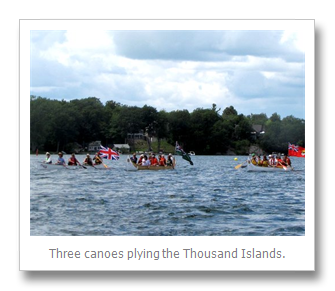

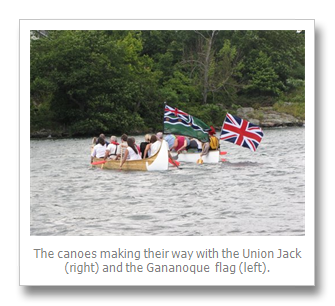

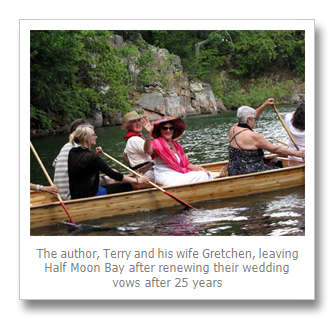

On August 3rd, 2013, Gretchen, my wife, and I were being paddled by ten costumed and outfitted ‘Voyageurs’, to Half Moon Bay, the “tallest cathedral ceiling”, to renew our marriage vows. We were in one of three 10-meter voyageur canoe replicas.

It was a beautiful sunny day, skies full of white puffy clouds, a light westerly blowing across the bows of the wedding ‘flotilla’. In true voyageur tradition French Canadian paddling songs were sung to the rhythm and cadence of the 30 paddlers. These beautifully decorated canoes were built by our nephew, Rob Mellan of Manitowaning, Ontario.

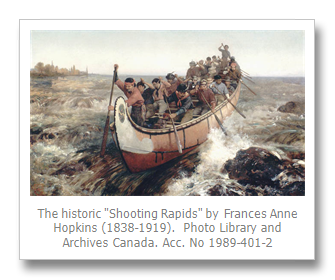

The steady rhythmic dip of the paddles, brought thoughts and images of the historic voyageur canoes, laden with trade goods, making their way west and north. These early voyageurs, paddling their birch bark canoes, were the very genesis of what would become a new country called ‘Canada’. The vast network of rivers and lakes they plied, at the end of the 17th century, influenced and secured elements of our national boundaries, as we know them today.

Canada, as a nation, was born by the sheer determination of the voyageurs to venture from Montreal, to the western-most interior, and set the stage for the next era of adventure, trade and migration to the west coast, validating the Canadian defining motto, ‘A Mari Usque Ad Mare’.

The voyageurs were true adventurers. They would leave Lachine, Quebec, in May and spend seven to eight weeks plying their heavily-laden freight canoes (“canots de maître”) up the St. Lawrence, along the Ottawa & Mattawa rivers, across Lake Nipissing, down the French River to Georgian Bay, through primitive wooden locks at Sault St. Marie and into Lake Superior, to the northern terminus, Le Grand Portage, now Thunder Bay Ontario. Here they would transfer to smaller canoes (“canots du nord”) and the next group of voyageurs would paddle & portage across Rainy Lake, Lake of the Woods, up the Winnipeg River into Lake Winnipeg and disperse along the North & South Saskatchewan rivers and up the Red River. Some headed north, up the Churchill River, dreading the arduous twelve-mile Merthy Portage, which linked the Athabascan country water network, with outlets in the Arctic & Pacific watersheds.

The “canots de maître” ranged from thirty-six to forty feet long with a four to five foot beam and weight about three-hundred pounds and manned by a dozen paddlers. Each canoe would carry seventy ninety-pound cargo bales.

By 1810 the trader supply line was over three thousand miles long. Their first rendezvous in “Le Grand Portage” was eighteen-hundred miles, from Lachine; this required paddling about thirty miles a day and labouring over the many portages.

Of particular commercial interest was the beaver pelt, which was in high demand, for the sheared beaver hats popular in fashionable England. However marten, fox, lynx, bear, otter, wolf, muskrat, and other furs, were in great demand in Europe and Asia. The trade and barter with Canada’s indigenous people was greatly influenced by the brutal competition between the two trading companies; the hoary, well-established Hudson Bay Company and the new ‘upstart’, more adventurous North West Company. Indian trappers were adept at playing off one company against another and a sense of mutual exploitation between trader and trapper. Indians felt that they had the better part of the bartering, given that they could trade near-worthless pelts for metal cookware, iron axes, blankets, woven cloth, steel needles and guns; previously they killed animals mainly for food. The traders however got furs at a fraction of their value in European markets.

The voyageurs travelled in brigades of five or six canoes, living a life of perilous adventure, grueling eighteen-hour days and boisterous camaraderie. According to Peter C. Newman, author of ‘Caesars of the Wilderness’, the voyageurs were “in effect, galley slaves, and their only reward was defiant pride in their own courage and endurance”. Paddlers starting out in the service were contracted for thirty British pounds per year but, once in the interior, were encouraged to get extra rum, tobacco and goods from the company stores. This invariably would render them more indentured and the resulting debt had to met by further service.

They also took pride in their flamboyant dress code; a short chemise, corduroy trousers, a pair of deerskin moccasins, red & black flannel shirts. Pants were tied at the knees, with beadwork garters, and held-up by a hand-woven sash, with a pipe and beaded tobacco pouch, hanging from the sash. Individuality was expressed more with head wear; a tasseled night bonnet, a coarse blue cloth cap, toques, colourful handkerchiefs, wound into turbans, with feathers attached. Their hair was kept long to better swish away the marauding flies that consistently attacked them. A concoction of bear grease and skunk urine, smeared on the expose skin, was applied to further discourage the persistent biting insects.

Each voyageur had a blanket, a “chemise”, a pair of trousers, two handkerchiefs, several pounds of carrot-shaped twists of tobacco and was limited to forty pounds for all his personal belongings. All trade and personal goods were packed into the ninety-pound bales.

Voyageurs were men of smaller stature; the average height was five feet six inches. Taller men would have occupied precious space in a canoe, already overloaded, with provisions & trade goods. The voyageur was short but strong. He paddled fifteen to eighteen hours a day,in all weather, for the six to eight weeks needed to reach Lake Superior. He would carry from one-hundred and eighty to three-hundred pounds, on his back, over rocky portages, at a pace that would have wrecked the average, unburdened, traveler. Each paddler would position a ninety pound bale in the small of his back, part of that weight borne by a tumpline across his forehead, and a second ninety pound bale was placed between the carrier’s shoulder blades;then the burdened man would dogtrot along the portage trail, knees and back bent, legs pumping rapidly and arms swinging free. The more ambitious voyageur could earn a Spanish silver dollar for each added bale he carried; this incentive sped up the portaging time. A five-mile portage could take up to two hours.

The length of a portage was computed by the number of “posés” or stops. At approximately every mile, or 10 minutes of dogtrotting, the voyageurs set-down their posé packs and then he ran back and shouldered the next load. The portages came to be measured by the number of posés.

To offset the paddling tedium the voyageurs would practice mimicking waterfowl, to perfect the cry of loons or the plaintive screech of gulls. And they sang! These were work songs; their unofficial anthem was a traditional song that I learned in (French) first grade, “À la Claire Fontaine”. Filled with double entendres, most songs were more profane than sacred. The tempo and cadence of the songs was in rhythm with the desired paddling rate, of forty-five to sixty strokes a minute. The steersman chose the song and tempo and set the pitch; he sang the stanza and the others joined-in on the chorus. Music was in the voyageur’s soul and evenings,after le souper, around a blazing campfire, they delighted in the rasp of a homemade violin or the twang of a mouth harp. With pipe smoke rising into dark lofty pines, the call for une chanson was issued. Those with any musical or dancing talent were highly thought of as travel companions.

The voyageur’s day began at four in the morning when the approaching dawn provided just enough light for the brigade to navigate by. They paddled quietly into the new morning, for twelve to fifteen miles, until the eight o’clock breakfast. Then a short shore stop would be ordered and a cold meal, prepared the night before, was taken with hot tea.

A light cold lunch was eaten while paddling and usually consisted of a piece of pemmican or a hard flour biscuit. Rest stops were made, for a few minutes each hour, to allow the men to “have a pipe”, so distances were measured in pipes: 3 pipes might equal 15 to 20 miles of travel. A 30 mile traverse would be ‘measured’ as six or seven pipes, always depending on wind and waves. Before evening meal, the canoes were offloaded, turned over for shelter from the elements and a tarp draped over the canoe, for protection from wind and rain. Le souper, cooked the previous night, was served warm. Through the night, a large iron kettle, filled with quantities of peas, strips of pork and water, was hung over the fire and simmered, till the cook added "biscuits" before breaking camp. The swelling of the peas and biscuit would fill the kettle and was so thick that a ladle would stand upright in it.

There were two designations of voyageur: the "Montreal Men", or "mangeur de lard", ("pork eaters"), and the “North Men” or "hivernants" (“winterers”). The Montreal Men paddled from Lachine to Le Grand Portage, near Thunder Bay Ontario, to rendezvous with the North Men,before turning back to Lachine. The "North Men" wintered in the northern interior and brought back furs to Grand Portage, to meet the summer brigades from Lachine.

At Height of Land, a portage rendezvous between Ontario and Minnesota, in the (now) Quetico Park is the ‘Laurentian Divide’ which separates the watersheds of the Atlantic and Arctic oceans. Here a rite of passage was practiced that would allow a Montreal Man to "become" a North Man. The newcomer was sprinkled with water from the first north-flowing stream, and made to promise never to kiss another voyageur’s wife without permission. This ended with the drinking of rum and a boisterous round of back-slapping, singing and dancing.

There was a pecking order in the canoes:

- The “avant” or bowman acted as the guide; he was experienced in the routing.

- The “gouvernail” or steersman, who sat or stood in the stern and steered, by order of the bowman.

- The “milieu” or middleman. Lowest of the ranks.

- The “express”, one who could endure a high rate of paddling for several hours.

- The “conducteur” or pilot, was the trail boss, judge and jury. A pilot was appointed for every brigade of 4 to 6 canoes.

Express canoes were used only to carry officials, dignitaries and messages. Because of the skill and experience required, the bowmen and steersmen were paid twice the rate of middlemen. Middlemen had less experience, but over time could become steersmen.

The voyageurs were often looked upon as manner-less, dirty men eating their rations from their pockets or hats and were not revered in polite company. The more fastidious owners of the companies considered them “profane and too volatile and sensual to suit the proprietor’s Presbyterian predilections”.

The most damning indictment was left by Daniel Harmon, a God-fearing Vermonter who spent fifteen years in the trader service of the North West Company. Peter C. Newman, quotes in his book “Caesars of the Wilderness”, (Viking Press) wrote, “They are not brave but when they apprehend a little danger they will often, as they say, play the man. They are very deceitful. And exceedingly smooth and polite, and are even gross flatterers to the face of a person, whom they will basely slander behind his back…..A secret they cannot keep. They rarely feel gratitude, though they are often generous. They are obedient but not faithful servants. By flattering their vanity, of which they do not have a little, they may be persuaded to undertake the most difficult enterprises….all their chat is about horses, dogs, canoes, women and strong men, who can fight a good battle.” Authority was a favourite taunt when travelling.

The larger canots de maître weighed about three-hundred pounds but could carry four tons. When packed, there would be only six inches of free board. As the trip wore on, the canoes would become waterlogged and their weight rose closer to five-hundred pounds. Despite their impressive capacity, the canoes were so frail that paddlers dare not change their position; during landings they were not dragged ashore. When stopping, the crewmen would leap-out and gently guide the canoe to the shoreline, to unload. These were easy to tip: It was said that one must “keep your tongue in the middle of your mouth” to prevent capsizing.

The two competing fur trading companies, the Hudson Bay Company and the North West Company, were the harbingers of the birth of a nation. They were willing surrogates of the British Empire, occupying lands for their own commercial purpose, but by virtue of their enterprise, safeguarded the territories until Canada developed its own aspirations to become a nation. We, as Canadians, owe them so much and celebrate their contribution.

Further Reading: 1. A passage from ‘Mon Canoe D’écorce’, (‘My Bark Canoe’) translated by Frank Oliver Call | Tu es mon compagnon de voyage!

Je veux mourir dans mon canot

Sur le tombeau, près du rivage,

Vous renverserez mon canot | When I must leave the great river

O bury me close to its wave

And let my canoe and my paddle

Be the only mark over my grave 2. Building the birch bark canoe: http://www.histoireforestiereoutaouais.ca/en/a7/ 3. Songs the Voyageurs would have sung, while paddling their canoes, found on youtube.com:

|

By Terry Bambrick

Terry Bambrick originally hales from Ottawa and worked in engineering management in the pulp and paper industry in Canada, USA and abroad. Terry and his wife, Gretchen, celebrated their 25th anniversary in 2013, by renewing their vows at Half Moon Bay, (Admiralty Islands). Their story was presented in the Our Past, Celebrated in the Present, December 2014 issue of “TI Life.” They were ferried to the ceremony in replica Voyageur Canoes built by their nephew, Rob Mellan, of Manitowaning, ON. Terry is also well known and popular in the Gananoque region for encouraging boating safety. Many a youngster (and adult) has been made a member of the 'River Mouse Club' when Terry finds them WEARING their life jackets. In June, 2015 Terry wrote It’s About Lifejackets (PFDs)…….it’s all about life.