There have been several islands that have gone by the name of Hog including the current McDonald Island in the Admiralty Islands. The two were sometimes confused in the early records. The Hog Island of this story is an island of about 3 acres in size and is part of a small group at the mouth of Halstead’s Bay, east of Gananoque, ON. The group’s most well known island, Gordon Island, is part of the Thousand Islands National Park system. The group is made up of Gordon, Jackstraw, Dobbs, Perch and, farthest east, Hog. They are located off the mainland point once called Sturdevant’s and now Chisamore’s. When boating by, one would never suspect the long and interesting history that some islands in this group have.

With absolute certainty, we can be sure that people have been visiting Hog Island for about 9,000 years. The earliest peoples chose Gordon Island for their encampments. In 1979 Dr JV Wright of the Museum of Man, in Ottawa, excavated at the island. There was continuous occupation that dated back to 7000 BC. It seems a given that the natives were hunting and foraging on the nearby islands and mainland as well.

This vast time scale can be difficult to grasp but from a genealogical point of view, with a rule of thumb of three generations per century, it is clear that people have been spending their summers in the Thousand Islands, for at least 270 generations. Ours is only the latest.

There is physical evidence of native presence on Hog Island from between 4,000 to 2,500 years ago. In 2012 Betty Sterken, co owner of the east side of the island with her husband Jack, was walking down a path when her eye caught something unusual on the ground. When she picked it up she immediately knew it was something important. It was a stone spear point about 3 ¼“ (8 cm) long by 1 ¾“ (4.5 cm) wide. It had waited thousands of years before presenting itself to Betty.

Tool styles are distinctive enough to be categorized as belonging to different cultures and, from archaeological experience, have approximate dates of manufacture. Although not officially dated, an internet search[i] indicated that it was most likely a Kramer point, up to 2,500 years old and from the Early Woodland period. A second opinion, from an archaeologist at the University of Western Ontario, speculated it could also be a Genesee point, or up to 4,000 years old and from the Late Archaic period. Interestingly, neither of the above points is represented in the artefacts discovered on Gordon.

From that grand perspective we move closer to the present. The natives of course continued to spend their summers in the islands but in the 1600’s new players arrived, the French[ii]. For the explorers and traders of New France the St Lawrence and the Ottawa rivers were their highways to the interior of the continent. Their route to Fort Cataraqui or Frontenac (now Kingston) took them by Hog and Gordon Islands. Gordon’s French name was Ile au Citron (Lemon Island). It isn’t clear if French pioneers to the new frontier settled around the Fort during the 1600’s but after the Iroquois-French war ended in the early 1700’s they certainly did. The river was safe to travel again. Many of the larger, fertile islands had French names and settlers and there was a demand for trades people at the fort. What names the natives and French gave to Hog will probably never be known. Grande Ile (Wolfe Island) and Ile Cochon[iii] (Howe Island) were the two largest and could supply the fort with fresh meat and produce in the summer. It isn’t known how many were seasonal or year round residents. Even Halstead’s Bay had been named by the French as Baie Corbeau. Corbeau, in its nautical sense, means grappling hook in French. An apt description of the turns to get into the bay from the east.

What follows is entirely speculation on my part but it will help to explain some future events. Some variation of this story is likely true.

“On a cool cloudy spring day in the early 1700’s a small party of canoes entered the bottom of Baie Corbeau on its way west to the fort at Cataraqui. The paddlers aimed for Ile au Citron and a welcome rest. As they approached the island a vicious squall closed in on them and drove them closer to the small islands near the mainland. The wind was fierce and the rain blinding. As they came abreast of the first island the increasingly large waves threw two of the canoes together, sending everyone and their belongings into the icy water. Most of the people managed to get to the rocky shore but three of the children drowned. Once the squall had passed, some of the other canoes, which had managed to get into the lee of the island, retrieved one of the bodies which hadn’t washed up on shore. After that they chased the drifting canoes and managed to take them into tow before they smashed on the rocks at the end of the bay. They salvaged what they could of the floating effects from the upset canoes.

Going any farther that day was out of the question so they set up camp on the island. The next day, after prayers, two distraught families and their companions buried the children. The best spot was in the center of the island, under some tall trees. Their shade kept the ground clear of undergrowth. It was tough digging, though, as there were rocks, the clay soil hard and the tree roots were everywhere. They managed to get down a couple of feet, deep enough that wild animals wouldn’t dig up the bodies. They covered the new graves with rocks that were abundant on the island both as markers but also to help protect the bodies. Small crosses were made from some branches. The next day the survivors continued west.

Every year the parents of the children stopped at the island on their way to Grande Ile and then on their way back home to Lachine in the fall. In the spring they had a summer of farming and fishing to look forward to. In the fall they could look forward to reuniting with their extended families and sharing good cheer over the winter. When they visited the island they would tell their deceased children of all the family happenings and how their brothers and sisters were growing. But the parents aged and finally died. As time passed the graves were largely forgotten, except as vague stories of long past generations. And then, no stories at all.”

|

By 1760 New France was no more and British control of North America was complete, for a while. In a few short years the American colonists rose up and created their own country. This brought on an influx of refugees who still wanted to live under the crown, the United Empire Loyalists. After them came a steady flow of immigrants from England, Scotland and Ireland, and new technologies.

Steamboats[iv] had an insatiable appetite for wood and soon the islands and the nearby mainland were stripped of their timber. Even for the newcomers the river was still a highway to the interior until the advent of passable roads and the railway. For the most part the new immigrants of that time viewed the river and islands as industrial and commercial assets not places to make homes. The steamers eventually had to import coal from the US but it was too late for the Indians. By 1856 the Mississauga Indians decided their hunting and fishing grounds had been destroyed and had moved west to the Bay of Quinte and then on to Rice Lake, near Peterborough. The islands were taken into trust by the Indian Affairs Department, who made plans to turn them into cash.

This opened the islands for purchase and/or settlement by the children of the first UEL settlers and newer arrivals. The Silas Cook family, Loyalists or late Loyalists, began to use Hog Island as a garden spot and a base for fishing on the River as early as 1856. Silas Jr was involved with the island while his brother, Cornelius, became the lighthouse keeper at the Gananoque Narrows and Jackstraw light. Cornelius lived on Stave Island.

Silas claimed in one letter[v] (items 4/5) to the Minister of the Interior that his offer to purchase was returned and he was told he could only apply after the survey that was to take place in 1873 by Charles Unwin. When Unwin did the survey, his report on Hog Island was short but referenced an issue that wouldn’t surface again for another 135 years. It states “Nearly all cleared, fair soil, has been ‘cropped’. There is a small shanty on it, and two or three graves.[vi]” This is the first mention of the graves in any records. Unlike what was to come, there appeared to be no curiosity at all about them in 1873. In all the various petitions and affidavits that were presented there is no mention of the graves, or deceased family members buried on the island. None of the current generation of the Cook family has any recollection of family members being buried on the island. The early Cook’s were buried on the mainland at the now abandoned Stratton Cemetery and then at the Cross Cemetery.

We know the approximate date of Silas’ use of the island from an affidavit by a John McDonald (item 22) in 1877 that vouched for Silas’ claim. In it he stated that “Silas L Cook has been in possession of said island ever since the year 1860, and for several years previous to that time.” In that affidavit and five others that Silas provided in 1880, the deponents (items 16-20) stated in various ways that they had assisted Silas in clearing bushes (no mention of trees even by the early 1860s) and rocks from the site to make it ready for planting. Those rocks likely included the rocks covering the graves. This was, most likely, how Silas knew there were graves there, and he is likely the one who reported the fact to Unwin.

The local land agent, though, seemed to have had some animosity towards Silas. In one letter to the Department of Indian Affairs he basically called Silas a liar, manipulator and poacher (items 8/9)[vii]. Fortunately, Silas found a powerful ally in the person of D Ford Jones. He was the owner of a large manufacturing company in Gananoque, Jones’ Shovel Company, and he was also Silas’ employer. And it certainly didn’t hurt that Jones was the local Member of Parliament. He wrote several letters to the Indian Affairs Department and arranged a payment schedule from Silas to the Department beginning in 1880. In 1891 Silas received the patent for the island.

The island stayed in the Cook family until 1953 when it was sold to Stanley Rutt, who didn’t appear to have made much use of it. Stanley held on to it until the late 1980s when he sold it to René Kurt of Switzerland. René had, a few years earlier, purchased Dobbs Island, and after discussions with friends in Europe, realized there was an opportunity waiting on Hog Island. His plan was to turn Hog Island into an international fishing lodge catering to Europeans who wanted to experience the Canadian wilderness, but with amenities and easy access to cities like Toronto, Ottawa and Montreal. The project progressed as far as obtaining site and septic approval for 15 units and a restaurant. He even managed to get the island rezoned as commercial. As far as is known it was the only totally commercial island in the Canadian 1000 Islands. The whole island was tested for soil depths and types to ensure it could support a septic field large enough to accommodate the project. And, a well was drilled that had the flow rate to support all those uses. It has to be one of the most studied islands on the river. But all that inspection of the island didn’t discover the once again forgotten graves.

This ambitious plan didn’t make it past the paper stage. The recession that struck North America in the early nineties gradually spread to Europe and Switzerland and the funds for the project dried up. Eventually the island was put up for sale and, after a long time on the market, was purchased by Jack and Betty Sterken and another couple.

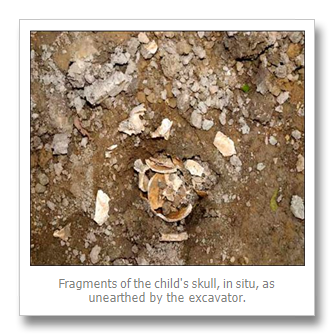

Given the scope of the first site approval and its commercial designation, they were free to build just about whatever they pleased. Jack and Betty built the first two cottages on the east side of the island. When the third was being built in 2008 a backhoe, digging for the foundation, once again brought the graves to the fore. They were only about 2 feet down in the dense clay. When the backhoe turned up part of a skull all work ceased and it became a potential crime scene involving round the clock OPP officers standing guard. That lasted for several days while various government departments had their look and decided what to do.

When the coroner decided it was of great age an anthropologist from Ottawa was called in. His inspection of the skull, and especially the teeth, determined that it was from a child between 7 and 11 years of age and “non native” and most likely represented a European pioneer burial. From his description of the examination of the remains it appears his primary purpose was to eliminate the possibility of the child being native. In a conversation with the Director of the Frontenac Heritage Foundation the anthropologist confirmed that the remains could date back to the 17th century (1600’s). The Frontenac Heritage Foundation was commissioned to do a class one archaeological report[viii] (background information only, no digging).

When it was determined the child was of European descent, everyone lost interest. A notice was posted in the Gananoque Reporter 24 September 2008. It invited “representatives of the persons interred” to contact the Registrar by the middle of October. After that the matter was forgotten. No further action was taken to identify the remains, do any archaeological investigation or designate the site as a cemetery. The remains were covered over and the process of forgetting is once again underway, 300 years after their first burial. Hopefully, this time they won’t be forgotten.

It was only the chance discovery by Unwin that the burials were even noticed and brought, in a roundabout way, to public attention. How many more graves are there in the islands caused by disease, misadventure or warfare? They would most likely be French but perhaps there are some English ones out there as well. Our greatest clue that there may be others is in the French name for Sherriff’s Point – Pointe a la Morte, Point of the Dead, or, more colloquially, Deadman’s Point.

To passing boaters it appears to be a small and unremarkable island not worth more than a glance but that is far from the truth. Hog Island has had a long and unique history, and many noteworthy connections to the extensive history of the area.

References

[i] Here are two sites for identification of early projectile points: www.ssc.uwo.ca/assoc/oas//points/sopoints.html and www.oocities.org/firefly1002000/pointsindex.html

[ii] For an overview of the French connection to the islands see: ‘The First Summer People’; Susan Weston Smith; 1993; Chapter One.

[iii] If we accept the Cochon spelling then we have another Hog Island as, in French, cochon means hog or pig.

[iv] For an overview of the river steamers see: ‘By Rail, Road and Water to Gananoque’; Douglas NW Smith; 1995; Chapter One

[v] There is a series of letters relating to the island online at Library and Archives Canada. It shows Silas’ attempts to purchase the island and some of the obstacles he had to overcome. See http://collectionscanada.gc.ca/pam_archives/index.php?fuseaction=genitem.displayItem&lang=eng&rec_nbr=2067862&rec_nbr_list=2067862 . There are 40 items, most of which deal with the Hog Island in this article. One deals with the Darling family and a Hog island near Ivy Lea or Rockport. A few near the end of the series of items deal with McDonald Island, then called Hog.

[vi] See Smith, p 141

[vii] Item 8/9; Collections Canada: This is an excerpt from the letter from the ‘Indian Land Agent’, AB Cowan of Gananoque to the Hon. David Mills, Minister of the Interior dated 19 Jan 1877: “I have to inform you that Mr Silas L Cook has promised from time to time to furnish the required affidavits in regard to the length of time he has occupied Hog Island in the River St Laurence but in every instance he has failed to fulfill his agreement. The last time I saw Mr Cook he gave me the names of two persons he had spoken to to make the required affidavits and that they would attend to it at once. I asked one of the persons he named if he Mr Cook had requested him to make affidavit and he replyed (sic) that he had never mentioned the subject to him. Judging from the manner in which Mr Cook is acting I am led to believe that he does not really want to purchase the island but only to keep the matter in suspense that he may occupy the island in question. After a careful inquiry in regard to the premtive (preemptive?) right of Mr Cook to the island in question I am of the opinion that his claim is not worthy of recognition. It would appear from what information I can get that he Mr Cook has not cultivated the island only in a very few instances and never resided upon the island only for a few weeks at a time, and then only for the purpose of carrying on illegal fishing.”

[viii] As a side note, in Ontario if anyone finds human remains on their property and reports it, they, not the archaeological investigators, are liable for all costs of the investigation.

|

By Paul Coté

Paul Coté is a resident of Gananoque. He has socialized and worked on the river for most of his life. History has always been a passion and he is a self confessed genealogy addict. Recently retired from contracting on the river, he now has time to pursue and write about his research. He is currently writing a book about the 500 year history of the Leeder family and shared some of that history in My Favourite Ancestor, August, 2015.