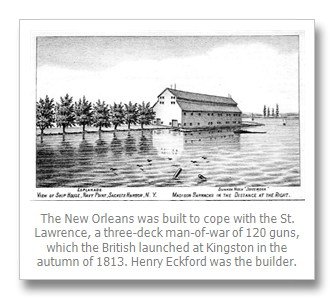

More than 200 years have elapsed since the virgin forest around Sackets Harbor was laid low by an army of axes and saws to make room for the ways of ships of the line. Here we would find the famous shipbuilder Henry Eckford supervising the skilful hands of New England shipwrights who worked side by side with not so skilful local carpenters whose talents did not reach beyond houses and barns.

But in many cases, remarkably short of a month, giant frames rose in place until there stood two mighty vessels ready for launching at Ship House Point and Storrs Harbor. Ship House or Navy Point, as it is called today, is a spit of land sloping down from a low hill helping to enclose Black River Bay on Lake Ontario.

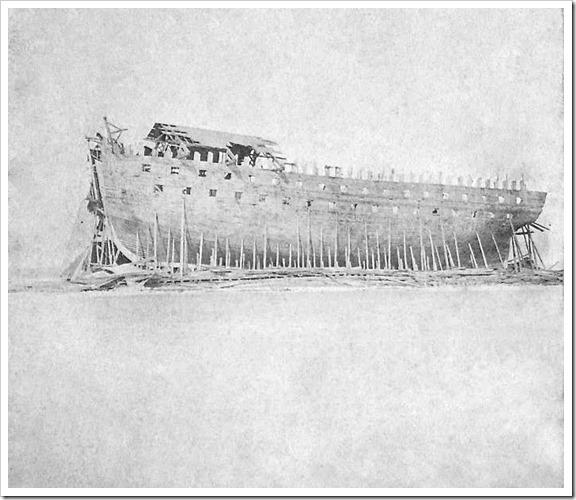

This is a depiction of the “New Orleans” left open to the elements after the ship-house protecting her finally collapsed in 1880. Photo R. Palmer Collection.

|

During the War of 1812, Sackets Harbor was a haven for dashing naval officers in ruffled shirts, heavily laced blue coats, huge cocked hats, skin-tight jersey pantaloons, and tasselled half-boots. In their wake rolled aging tars in blue shirts and wide trousers. They told competing tales of distant seas salted with strange oaths. Oldest veterans among them still wore their hair in a pigtail.

On the bluff across the mouth of the harbor, opposite Ship House Point, a rude log fort had been erected in 1812 along with a central block-house surrounded by a stockade, mounting a few pieces of artillery. From a tall staff` on the parade ground the Stars and Stripes flew in amicable salute toward a similar ensign hoisted at the point.

Military storehouses filled with munitions and supplies stood back from the wharves crowded with vessels. Enlivening the town were soldiers, ship carpenters, woodcutters and sailors. Sometimes the white sails of the American and English squadrons could be seen on the lake. On summer days on the distant horizon might be heard the dull boom of cannon where an engagement was on.

More than once a melancholy and shattered ship brought in a ghastly cargo of dead, dying and wounded, the care of which taxed the community. The women of the village bore the brunt of it, learning the grim lessons of war.

Sackets Harbor sprang alive amid all this activity as if by magic - quite as the great ships had risen on the shore so quickly. But men did things in a hurry in those days, and no one was much surprised when, some 30 days after the keel was laid, Eckford informed Commodore Isaac Chauncey, American commander on the lakes, that the “New Orleans” and “Chippewa” would be ready for launching by April 1, 1815.

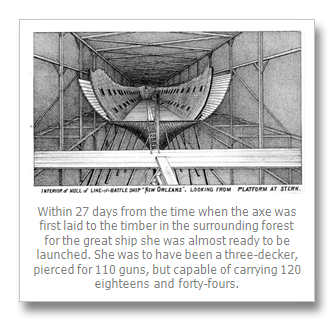

It was a busy scene, and pressure was brought to bear by Eckford, who was constantly rushing about, inspecting every detail. Most of the timbers for both vessels and supplies for a third came from the surrounding region. It is said that more than 500 men worked just building the “New Orleans.” Both she and the “Chippewa” would have been larger than any ocean-going gunships that existed at that time.

The primary problem with building ships so rapidly is green wood. They would have decayed rapidly. The “New Orleans” was 212 feet overall; 3,200 tonnage; 183 feet, 7 1/2 inches keel length; 56 feet beam; 30 feet depth, and 27 feet draft. It is said the “Chippewa” had approximately the same dimensions.

Both vessels would probably have been armed with no larger guns than 42-pounders. In actuality, both vessels were pierced to carry 110 guns each, but could carry 120 guns if needed.

The two vessels were being built not only to offset Sir James Lucas Yeo’s great ship of the line “St. Lawrence,” which was built before these were started, but to give Chauncey a balance of tire power. The “St. Lawrence” was launched, rigged and under sail by October 15, 1814. She was somewhat smaller than those being built at Sackets, being of 2,304 tons, carrying 102 guns on her three decks. The armament consisted of 34 32-pound carronades on her lower deck, 32 24-pound long carronades on the main deck and 34 long 32-pounders on the upper deck. She was 191 feet overall length; 171 1/2 feet keel; 52 feet, 5 inches beam, and 27 foot draft. She was considerably larger than Horatio Nelson’s “Victory” which won the Battle of Trafalgar against the Spaniards, and still exists as a museum in Portsmouth, England.

Construction work on the two vessels did not progress that summer beyond laying the keels. The shipwrights were busy finishing and fitting out existing ships. It wasn’t until December 18, 1814, that Chauncey ordered New York shipbuilders Adam and Noah Brown and Eckford to Sackets Harbor to “make selection of such spots as in your opinion may be the most eligible for building with dispatch two ships of the Line and one Frigate. Your selection will not extend beyond Storr’s Harbor.”

What is remarkable about the rapidity of shipbuilding at Sackets Harbor was the number of men employed in construction. By mid January, 1 815, more than 600 ship carpenters were on the scene. A newspaper correspondent noted that the men were “busily engaged in getting timber ready to build two seventy-fours and a Frigate of the first class. Although surrounded by spies, our government have reason to congratulate themselves on this one very essential point - that the whole of the materials for the increased naval force to be established on this lake has been contracted for, and ready for delivery these six weeks.” The article was written on January 11, 1815.

On February 1, Chauncey advised B. W. Crowninshield, Secretary of the Navy, that work on the ships was progressing rapidly and the frames had been raised. “The builders,” said Chauncey, “assure me that they shall both be launched in April - the Frigate is not yet commenced but the materials will be prepared for her_ so that she can be built in a short time.”

Regarding the Frigate, Chauncey queried, “Would it not be advisable to give her so much beam as to bear two tier of guns in case the enemy should increase his force beyond what we at present expect? I hope to hear from Kingston in a few days when I shall learn what is building there.”

Also employed in the shipbuilding frenzy at Sackets Harbor were 60 ship-joiners, 75 blacksmiths, 25 block and pump-makers, 10 boat builders, 10 spar-makers, 18 gun-carriage makers, 16 sail masters, 10 armorers and 5 tin men, for a total of 829.

Eckford and the Browns intended to build a fleet for Chauncey that would give him naval superiority on the lake. Noah Brown recalled: “In February, 1815, we received orders to proceed to Sackets Harbor, to build, in company with Mr. Eckford, two large ships to mount one hundred thirty guns of very large calibre; hundred pounders on the lower deck and thirty- two on the upper deck; likewise, three large size frigates.”

Governor D. D. Tompkins was advised by Chauncey on February 16th that caulking would commence in two days and would be ready to launch by the last of March “unless Peace prove true and stops us where we are.”

Captain Britell Minor of Three Mile Bay, although only about fourteen years old at the time, had a vivid recollection of the flurry of activity at Sackets Harbor at the time. He watched workmen ready the timbers for the “New Orleans” and noted how every available spot in the village was taken up in shaping material for the big ship.

The Stop Order

The treaty of Ghent ending the War of 1812 was signed on December 24, 1814, but news that would end hostilities on the Great Lakes did not reach Sackets Harbor until late in February, 1815. The Browns and Eckford were advised by Chauncey on February 23 to suspend work on constructing the ships.

In a letter to Crowninshield on February 25, Chauncey wrote: “I have suspended all contracts and stopped the transportation of all stores except those between this place and Utica which must come here for safe keeping. I have directed Messrs. Eckford & Brown to discontinue all building - these gentlemen however state to me it is impossible for them to stop so suddenly because they have upwards of 800 men employed which must be paid work or play until they arrive in New York - consequently it costs no more to keep them at work than suffer them to remain idle - they reduce their gangs thirty to forty men per day which is as many as they can find transport for.

“I have directed a survey upon the two ships and the timber for the third one to enable the department to settle with those gentlemen on fair terms. As the two ships are in that state of forwardness that they could be launched in four weeks I presume that it would have been in the interest of the Government to have launched and sunk them between piers in which state they would have lasted for ages. If left on the stocks they must be housed or they will decay in a few years.”

Amos Benedict, Jacob Jones (commander of the Mohawk) and William M. Crane completed their survey of the two ships on March 18, 1815. The document gives some interesting details concerning the vessels. It states the contracts for the ships were signed on December 15, 1814. The “New Orleans” had been planked up to the upper deck, fitted in between the ports, squared off and bottom half caulked. They reported that the “Chippewa” was not in the same state of forwardness, owing to the “situation” of the place.

When work commenced there were no buildings within a mile of the place. Before work started the Navy had to erect a building suitable for 400 men, another for inside work, as well as a blacksmith shop, joiners shop and a guard house. By early March, however, the “Chippewa” had been framed and bottom planked. The masts, spars and iron work were at a considerable state of forwardness. Also on hand was the timber for building the frigate, which was never constructed, which was to be called the “Plattsburgh.”

According to the report, about 400 men were working on each ship. Workmen each received $1.70 per day wages and $4.00 a week for board. It was estimated that the “New Orleans” could have been completed in 31 days. The frigate, to be built at Sackets Harbor, would have had a 185-foot keel, 46-foot beam, and would have been ready to raise as soon as the New Orleans was launched. It would have been ready to launch in 40 days.

It is said that much of the timber, especially the masts, were cut in the vicinity of Antwerp, some 20 miles to the east, and hauled to Sackets Harbor by teams. However, there also was a large amount of timber cut from forests closer to Sackets Harbor. Silas Lyman, an old-timer, recalled in 1880: “Of the old ship I will just say, I was at work on a big oak tree about a mile south of the Harbor, when word came, ‘no more ship timber.’ Peace was declared.”

Chauncey advised John Bullus, Navy Agent in New York, on March 5, 1815 that the only instruction he had received up to that time was to suspend construction. These instructions were dated February 14. “The mechanics however have broke off and gone home,” Chauncey said, adding: “We are waiting with some anxiety for further orders. I have suspended all contracts with all the people that I had anything to do with.”

Best Enemies

In a private letter March 3, Chauncey wrote to Commodore Sir James L. Yeo, his old enemy, inviting him to visit Sackets Harbor, should he return to England via New York. He said, “I should be most happy to offer my hand as a friend to one who I have contended with as an Enemy and for whose character l have the highest respect.” Yeo accepted Chauncey’s invitation and upon his visit was astonished at the rapidity with which the two ships had been built.

Fleet Lay-Up

Chauncey subsequently had the naval fleet on Lake Ontario dismantled. Most of the vessels built at Sackets Harbor were laid up in ordinary and the merchant vessels resold back to their original owners. The military personnel, with the exception of a small housekeeping contingent, were transferred to the sea coast. During the summer of 1815, Chauncey took command of the ship of the line “Washington,” at Portsmouth, New Hampshire, subsequent to which he continued a distinguished career in the Navy. Twice during his-career he commanded the New York navy yard, and just prior to his death in 1840, was navy commissioner in Washington, D. C.

Upon Chauncey’s advice, ship houses were erected over the “New Orleans” and “Chippewa” in August, 1815, at a cost of $25,000. Noah Brown reflected: “Peace coming on, we did not complete our contract but we got the large ships in great forwardness, we proceeded on to the Harbor with about 1,200 men; and when we were stopped, in six weeks longer, both large ships would have been completed and in the lake. But we returned to New York and had not the pleasure of seeing the largest ship afloat in the inland waters of our State that was ever built.”

The fort was dismantled, the garrison mustered out, and the storehouses emptied and closed. The young ships were left alone with the almost- abandoned village. The busy places, their reason for existence gone, speedily sank into decay. The deserted storehouses fell into ruin. The once noisy wharves, unvisited by any save an occasional small vessel, rotted away. The merchants and traders closed out their stocks and departed. Grass grew on the silent streets, and it seemed the village’s fate was sealed.

Shipwright Visits the “New Orleans”

With the war now over, in February, 1816, John Aldersley, a British foreman of shipwrights at Kingston visited Sackets Harbor to examine the workmanship on the uncompleted New Orleans. He met his escort, a Lieutenant German, aboard the “Superior,” which was laid up in ordinary. After touring that ship, Aldersley then walked over to inspect the “New Orleans ” and was appalled at what he saw. He said, “I was not in the least impressed at their building or rather making ships in so short a time. The first thing which caught my attention was the frames. I never could have believed if I had not seen it: the most abominable, neglectful, slovenly work ever performed, no regard for heads, heels or scarphs of timbers, nor even the posts. The timbers are in many instances thrown in one upon the other, without even the bark of the tree being taken off.” Aldersley noted that the gun ports were created after the ship’s sides were completed, “the same as the doors and windows are cut out after a log house is framed.” 2

At least on Lake Ontario, the War of 1812 was one of shipbuilding. There were no major naval battles on Lake Ontario when compared with those on Lake Erie in 1813 and Lake Champlain in 1814. But the shipbuilding frenzy on Lake Ontario far surpassed those on the other lakes. Shipwrights at Sackets Harbor and at Kingston, vied with each other to see who could build the biggest fleet of warships to maintain control of the lake.

Such competition led to rapid and often slip-shod work. It was not unusual to take two or three years on the Atlantic coast to build a large frigate. At Sackets Harbor it was done in two months. It only took 45 days from the the time the keel was laid for the 24-gun Madison until it was launched and put into service. Such construction required skilled ship carpenters -something Sackets Harbor was always seemingly short on. , and at Sackets Harbor there were never enough of them. This gap was filled by hiring local house carpenters. Building a house or a barn is quite different than building a ship.

As a result, Henry Eckford compensated for this shortcoming by altering the design to make the vessels easier (and faster) to build. In one case this brought disastrous results. In September 1814, the 22-gun brig “Jefferson” encountered a fierce Lake Ontario gale. Rolling “twice on her beam ends” she began to come apart. To save the ship, the captain, Charles Ridgely, to save the ship, lightened her by throwing 10 cannons overboard.

Most of the completed warships did not survive for long since they were constructed of green wood. “Sunk and decayed” is what appeared on reports. But these terse comments did not apply to the incomplete “New Orleans” and “Chippewa” that remained in reasonably good condition as long as they were protected under the ship-houses.

Post War Sackets Harbor

As the years passed, some of the pristine life returned to Sackets Harbor. The farmer again put his plow to the rich soil and planted his com. Sheep and cattle once more roamed the fields denuded of trees during the shipbuilding frenzy.

A new order took the place of the old. Country churches rose along with the little red school houses. The stores reopened one by one, and merchant ships again made it an important port of call on Lake Ontario. There also was considerable shipbuilding in subsequent years. On market days, the farmers crowded the square with their harvests.

The village awoke from its long sleep and became a modestly thriving little country town again, largely due to the establishment of Madison Barracks, a northern frontier Army post that gained considerable distinction in subsequent years. But the old inhabitants knew it would never be the same, although younger people were content and happy in their pretty little village.

The “Chippewa,” like the “New Orleans,” remained under cover for years. However, she was broken up and burned on the ways for her old iron in 1834. In l842 the condition of the New Orleans was surveyed and found to be not too badly dry rotted2.

Still ‘Combat Ready’ in 1860

Military historian Benjamin Lossing, on the trail for material for what became his monumental “Pictorial History of the War of 1812”, visited Sackets Harbor during the summer of 1860. His tour guide was Commodore Josiah Tattnall, one oft he most distinguished naval officers of the day. At the time he was 64 years old and had been given the command of Sackets Harbor naval station “to enjoy a season of rest.”

The two walked to Navy Point to inspect the “New Orleans.”. Lossing noted that the big three-decker was perfectly preserved under the roof of the ship house. He was told “that within 27 days from the time when the axe was first laid to the timber in the surrounding forest for the great ship she was almost ready to be launched.”

Nearby, on the south side of the building, they inspected the sunken hulk of the “Jefferson” which had a ghostly tendency to make its presence known during times of low water.

The following year Tattnall would resign his commission to join the Confederacy. Although considered a traitor and “misguided” by the North at the time. But he was a Southerner by birthright. He was born at Bonaventure, four miles from Savannah, Georgia, in 1796. During the Civil War he would distinguish himself for his service in the Confederate Navy.

The “New Orleans” again came into the limelight late in the fall of 1861 when the Union became concerned over its northern defenses with the unfounded fear Canada would become an ally of the South. Secretary of State William H. Seward, in a letter to the governors of the northern “loyal”states, noted that Lake Erie was entirely under U.S. control and in possession of “hundreds of staunch propellers” which could be converted into an armed flotilla in a very short time.

Seward thought the U.S. was particularly vulnerable on Lake Ontario, inasmuch as Kingston was one of the finest harbors on the Great Lakes and had one of the finest fortifications on this continent. In sharp contrast were the defenses of Oswego and Sackets Harbor, long since gone to decay that would require huge sums of money to put them in proper order for defense.

Seward noted: “But at Sacket’s Harbor we have on the stocks and under cover an eighty gun ship, of which, until very recently, the brave but misguided Tatnall was commander. This ship is still sound, except in a few parts, and a recent examination of her by competent persons, has resulted in the adoption of the opinion, that she can be set afloat, ready for service, in ninety days. In addition to this, it is believed that she can be turned into a propeller with entire success, and thus be made a floating fort, which would, in case of war, secure us the command of the lake, and enable us to prevent the construction of a rival fleet, and destroy, if necessary, the forts on the Canadian shore. This, then, is a method of securing our shores on Lake Ontario - at once practicable, economical and decisive.”

It does not appear that the U.S. Navy ever gave Seward’s proposal to resurrect the New Orleans any serious consideration. Although there may have been some sympathizers for the Confederacy in Canada, this area never was considered a renewed military war front.

The naval station at Sackets Harbor, particularly in the later years of the 19th century, became an anachronism with no real justification for its existence. Navy Point was reduced to the four acres of the hook-shaped spit and a strip along the brow of the promontory. For a time, it was fully officered, having its own commandant and captain of the yard.

Other distinguished officers who more or less bided their time here at the end of their careers until it was finally their time to retire included Captain George N. Hollins, another Secessionist commodore, and Rear Admiral J. B. Montgomery, who had received his midshipman’s commission here in 1812. He returned here 54 years later to command this, the smallest yard in the U.S. Navy.

In the 1870s the yard was forgotten for all intensive purposes. However, the buildings were kept scrupulously neat as were the grounds and the docks. The unfinished hull of the “New Orleans” was cared for as much as funds would allow by a skeleton crew of master carpenter, ship-keeper and mechanics, who held easy jobs in their declining years. They puttered around the place tidying and sweeping, awaiting word that never came to launch the ship.

A succession of “ship-keepers” justified their existence by filing occasional financial statements and reports with the naval headquarters in Washington, D.C. One in particular, Albert H. Metcalf, took his job seriously and prevailed upon his superiors to spend some money on maintenance of the ship house. His appeal fell on deaf ears.

Finally, on September 17, 1879, a gale ripped off 15 square feet of the roof, carrying away some rafters and timbers. He recommended replacement. On December 22, another gale carried away about a third of the west side of the structure.

If for no other reason, the “New Orleans” became a major attraction, with naval officers giving guided tours. It looked astonishingly like Noah’s Ark. It is said that probably 40,000 per people visited the place over a period of 40 years. Early in 1880, the ship house began to show signs of weakness and every day or so some pieces of it blew off.

One day, two enterprising Watertown men conceived the idea of burning the ship as a public spectacle. First they would purchase the property from the Navy for almost nothing. Next, they would charter all the steamboats in this section of the country for a day during the summer. They also would charter special trains to Sackets Harbor. Then, they would lease the Earle House and Eveleigh House, two local hotels, the unoccupied stores at Madison Barracks for the day, to accommodate the crowd.

Next, they would sell sitting and standing room in sight of the old ship house, and that night, set the landmark on fire. But they never followed through with this money-making scheme.

Perhaps this would have been a more appropriate ending than was the actual fate of the “New Orleans” a few years later. What remained of the roof, the northeast side and half of the southwest side of the house were blown away, making a complete wreck of the building. Only a small portion of the southeast and northeast comers remained standing. Metcalf watched his charge crumble before his eyes.

The “Jefferson County Journal of Adams” reported on February 11, 1880 that “the old ship-house, the Coliseum of Sackets Harbor, suffers additional destruction by such wintry gales, and soon will be a shapeless pile of ruins and its existence only perpetuated on the pages of history.”

The same newspaper, on March 3, 1880 reported, “The last vestige of the old Ship House fell with a great crash on the afternoon of the 18th, and now there is an unobstructed view of the old Leviathan on all sides, from the keel upwards. ADIOS, thou wrecked memento of the War of 1812, may this frontier never have reason to regret thy decayed dissolution.”

Public Auction

The Navy finally decided to dispose of the “New Orleans” and eliminate this liability that could prove a safety hazard. So it was that at at a public auction on September 24, 1883, Syracuse businessman Alfred Wilkinson found himself the proud possessor of an authentic War of 1812 ship of the line (unfinished) for $427.50.

Wilkinson engaged contracted the services of Jolm Hemans, a wrecker from Mexico Point, to dismantle the vessel. On November 9, 1883, Metcalf officially delivered up the “New Orleans” to Hemans. The demolition of the vessel started as soon as Hemans was able to hire a gang of men, mostly local residents. No further mention of the demolition work appears in either official records or the newspapers until February 9, 1884, when one of the workmen was killed.

The men reported to work as usual that Saturday morning. But some were reluctant to continue after it was discovered the hulk had slipped back about four inches off the blockings during the night. Others laughed it off and the work progressed safely until about 10:30 a.m. They were sawing off a section of

the ship when a crashing sound was heard and she began to slide back. The vessel moved about 10 feet when it snapped literally in two, falling and carrying the men down with her. One man was on a ladder when the alarm was given. He fell off the ladder about 15 feet. He was caught in such a manner that the beams covered him without touching him. He escaped with a severe blow to the head which dazed him. The other workmen, with the exception of John Oats, 29, of Sackets Harbor, escaped with slight injuries.

One oft the falling timbers containing a square two-inch bolt fell across his body, piercing him and coming out the back. A large spike was driven into his head, and he died instantly. Alarmed by this news, Mr. Wilkinson immediately telegraphed Sackets as soon as he learned of the news, expressing his concerns, and stating he would provide for the injured and defray Mr. Oats’ funeral expenses.

The editor of the Jefferson County Journal wrote on February 13 that Hemans had been warned about the unsafe condition of the ship “by an old and experienced Captain,” who told him how to make the proper precautionary measures to protect the lives of the workmen. Hemans said he “would stand all the damage,” so nothing further was said.

On February 17, 1884, ship-keeper Metcalf reported the accident to the Navy’s Bureau of Yards and Docks. He said he felt the accident could have been avoided if John Hemans, the foreman, had taken his advice. Metcalf said, “I warned him to put up preventer shores to hold her from starting back on her blockings and to keep her topsides from spreading, which he omitted to do, he got along with his work well until the day of the accident.”

No official blame was attached to anyone. Work resumed immediately and appears to have continued until March. Wilkinson realized about $4,000 from his investment. There were 30,000 shingles left over from the ship house which were sold for about $2.50 per bunch. Some 50 tons of iron from the vessel brought $30 a ton, and 18 cords of red cedar were sold for $12 to $15 a cord.

However, there was a large quantity of wood and iron of little value. The portion sold as stove wood brought about $1 per cord. The better lumber was sold locally for building materials. Over the years, bits and pieces of the ship and house had been taken as souvenirs, shaped into such useful utensils as walking sticks, knife handles and bootjacks. Some of the iron spikes were fashioned into cane heads at the foundry of W. L. McKee.

Still other portions of the ship became chairs, clothes-bars, book shelves and other pieces of furniture. Farmers bought planking to use in houses, barns and other structures. Some of the planking and woodwork measured 30 feet by 24 inches by three inches - solid oak. There were deck beams of pine two feet square which ran the full width of the ship.

Much of the oak from the ship was sawed up for flooring in George Hoover’s sawmill in nearby Dexter. Much red cedar was used in the construction on the inside of the ship between the main ribs of white oak. It was naturally in odd lengths and too full of nail holes to be of use for many purposes. Thus it lay piled along the shore for a couple of years before being sold to a pencil factory.

A Cane for FDR

When then Governor Franklin D. Roosevelt visited Sackets Harbor in the summer of 1929, Charles Colton, a local resident, presented him with a cane made from the “New Orleans.” Colton told Roosevelt:

“I am delighted with your interest in the history of the cane made from the frigate “New Orleans” and all things pertaining to the naval history of Sackets Harbor. Elliot Roat of Pillar Point made your cane out of oak from the old ship for his brother George Roat. Mr. Roat was a carpenter and boat builder.

“I do not know how much of the lumber he had or may have made into souvenirs. George Roat moved to Sackets Harbor in later years and shortly before his death he gave this cane to a blind friend, James Daly, who still lives here. Mr. Daly found a cane he could hang upon his arm better suited to his convenience so he gave the cane to me. When I heard you were coming to Sackets Harbor I decided to give the cane to you because I wanted someone to have it who deserves it and would appreciate it.

“It is regrettable that so much of its interesting history is becoming more folklore than fact. I followed the threshing business for 18 years and two feeding pins for the threshing machine were made of iron from the old ship. Very likely it was put to hundreds of prosaic uses in that day that would be of romantic interest now.”

Mr. Colton concluded: “We appreciate your interest in our locality past and present and are honored by your visits as Secretary of the Navy and as Governor of New York. May we look forward to your coming again with the highest honors that the nation can confer upon you.”

The story of the “New Orleans” continues to haunt this historic village well over a century after its demise, along with its more obviously desecrated relics of the past such as Madison Barracks and Fort Pike.

Bibliography

Books

- Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships (8 volumes) U.S. Navy Department.

- Brady, Cyrus T., Woven with the Ship - A Novel of 1865, J.P. Lippincott Co., Philadelphia &

- London, 1902.

- Chapelle, Howard I., The History of the American Sailing Navy, New York, 1949.

- Cooper, James Fenimore, Lives of Distinguished American Naval Officers, Aubum, N.Y., 1846.

- Cumberland, Barlow. The Navies on Lake Ontario in the War of 1812. Ontario Historical Society Papers and Records, Vol. VIII, Toronto, 1907.

- Cuthbertson, George A., Freshwater, Toronto, 1921.

- Hough, Franklin B., History of Jefferson County, N.Y., Albany, 1854.

- James, William, A Full and Correct Account of the Military Occurrences of the Late War Between Great

- Britain and the United States of America. Two volumes London, 1818.

- Landon, Harry F., Bugles on the Border (Watertown Times publisher) 1954.

- Lossing, Benson, Pictorial Field Book of the War of 1812. New York, 1868.

- Lucas, C.P., The Canadian War of 18l2. 1906

- Snider, C.H.J. The Mighty St. Lawrence Dreadnought of the Lakes, Toronto Telegram, April 17, 1934

- Van Cleve, Captain James, Reminiscences of the Early Period of Sailing Vessels and Steamboats on Lake Ontario Mss. 1877 Unpublished manuscript in City of Oswego, N.Y. clerk’s office

Other References

- Enrollment records for Oswego, N.Y. Record Group 41, National Archives.

- A Return of Vessels of War belonging to the United States upon Lake Ontario Exhibiting Their Force in

- Guns and Men dated June 15, 1814 National Archives.

- Oswego Weekly Palladium.

- Sackets Harbor Gazette.

- Papers of Isaac Chauncey, New York Historical Society.

- Watertown Daily Times, Jan. 29, 1930. Article by Jean Crowell on the New Orleans.

- Geneva Gazette, February 15, 1815. Geneva, N.Y., and various issues.

- American State Papers.

- Letterbooks of Commodore Isaac Chauncey, New York Historical Society collections, New York City.

- Sackets Harbor Battlefield Historic Site pamphlet, Jessie E. Besaw, Historical Researcher.

- Document No. 23, 23d Congress, 2d Session, House of Reps. Dec. 27, 1834.

- Jefferson County Historical Society Bulletin Vol. 1, No. 16; Vol. 5, No. 20.

- Daily British Whig, Kingston, Ontario, Jan. 13, 1880

- Dictionary of American Biography.

- Onondaga Historical Association file (Syracuse, N.Y.) on Alfred Wilkinson.

____________

|

Note 1. House document 225, 27th Congress, 2nd Session:

Report of the condition of the ship of the line “New Orleans”, lying in the ship-house at Sacket’s Harbor, by A.P. Upshur, dated May 14, 1832. He wrote:

-

-

The four spices of the keel much decayed by dry rot, though there is no appearance of the rot on the outside. The floor timbers, alter boring into them in every direction, l found about one-half of them badly affected by dry rot; the other half good and sound.

-

The part of the keelson that is bolted down is affected by dry rot; the other part of the stem and apron defective from dry rot; the upper pan of both is sound.

-

The stem post is defective its whole length. Transoms all good except the lower one, which is partially decayed by dry rot.

-

The timber of the ship I found good from about l8 feet from the keel upwards; below that, to the keel, affected by dry rot.

-

The entire sealing or inside plank l found perfectly good. The outside plank I found good, except in a few places. The beams are all good, and bolted down to the clamps.

-

There are no clamps or sealing in the ship above the lower gun deck, and the sides of the ship between the ports are timbered with cedar.

-

On the outside, the ship is planked entirely, with the exception of her stem, which is open above the main transom.

Note 2. Letter from John Aldersley to William Fitz William Owen, Kingston, February14, 1816. British Archive Film Roll B-2786

|

___________

By Richard F. Palmer

Richard F. Palmer is a retired newspaper editor and reporter and well known for his weekly historical columns for the “Oswego Palladium-Times” called "On the Waterfront." His latest book is the biography of Captain Augustus Hinckley, famed Lake Ontario and St. Lawrence River mariner, as well as a review of the maritime history of Clayton, NY. He is also a regular contributor to the Maritime History of the Great Lakes website and is frequently consulted by people searching for shipwrecks on Lake Ontario.