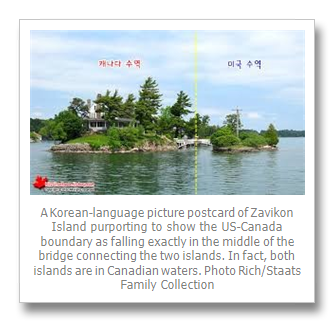

The story of Zavikon Island during the period ca. 1947 – 1970, is closely connected with that of the Rich family of Woolrich, Pennsylvania, USA, and their company, Woolrich Woolen Mills (now Woolrich, Inc.) It’s difficult to know the one without knowing the other.

Briefly, John Rich, II (1786 – 1870) was born in Wiltshire, England. Soon after his birth the family moved to Wooley, East Yorkshire, where he learned wool carding from his father. Of John’s formal education, the less said the better.

John immigrated to Philadelphia in 1811 and obtained work as a wool carder in nearby Germantown. John married Rachel McCloskey (1807 – 1868) in 1825. They had one child, John Fleming Rich (1826 – 1888).

Not long after, John Rich II and his family moved to Mill Hall, PA and rented a small woolen mill that he operated for seven years. He also bought a mill at Cooperstown, PA and held part interest in another. During that time John and a partner built a mill on Plumb Run in Clinton County. He purchased his partner’s interest in the Plumb Run Mill in 1843, and moved all the equipment two miles to the north, where he had built a new mill out of homemade brick (the first of its kind in Pennsylvania) in a place he named Factoryville (subsequently renamed Richville and then Woolrich). In 1839, John resettled his destitute father, John Rich (1759 – 1847) from Wooley to Woolrich.

Described as a “liberal Christian”, John generously supported the Methodist Church, especially with its building projects, such as the Woolrich Community Methodist Church. He also served as a commissioner of Clinton County and as county auditor-in-chief. His mills have remained closely held in family hands, since their formal organization as a single company, in 1830. During the Great Depression, no employee was fired or had his work hours or salary reduced. The mill was never unionized.

Robert Fleming Rich (1883 – 1968), John II’s great-grandson and my grandfather, was an athlete, a sportsman devoted to hunting and fishing, and a strict Methodist who neither smoked, drank alcohol nor used intemperate language. His one vice was gambling: at cards and golf. My grandfather was a scratch golfer, but was outmatched by his caddy, a young man named Arnold Palmer.

More often than not my grandfather won his bets. At one Saturday night poker game in 1933 with other legislators, he left the table with $350 in winnings, all of which he placed in the church collection plate the next morning.

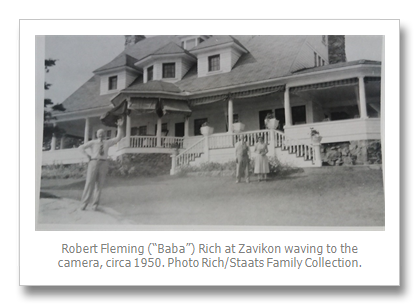

From 1931 to 1953, my grandfather, “Baba” to his grandchildren, was a member of the US House of Representatives, for the 16th (and later, after redistricting, the 15th) congressional district of Pennsylvania. A conservative Republican, he championed the candidacy of General Douglas MacArthur, in the 1948 presidential primaries. The convention, however, chose New York Governor Thomas Dewey, as its standard bearer. Dewey lost to Truman. My grandfather retired from active politics in 1953 at the age of 60, when Dwight D. Eisenhower became president, and returned to Woolrich to run the company.

Baba and his first wife (my grandmother, Julia, 1886 – 1951, married 1911 – 1951, née Trump; “Gah-gie” to the grandchildren) had four daughters (eldest to youngest): Elizabeth (“Ibbie”), Margaret (“Margie”, my mother), Catherine (“Katie”), and Julia (“Julie”). My grandparents bought Zavikon in 1947, as a summer vacation spot for themselves, and later the entire family. Katie and her family never visited to Zavikon, preferring instead their own waterfront vacation home in Westport, Massachusetts.

The story – possibly apocryphal – that I was told of how Zavikon was acquired, is that the owner in 1947 had rented the island each year to businessmen, who had used Zavikon as an “executive retreat”, where they, accompanied by women who were not their wives, gathered to “conduct business”. The public was indignant when the story broke. The owner vowed to sell Zavikon to the first bidder. My grandfather had a quick eye for value and reportedly got the island – lock, stock and barrel – for $10,000.

My first complete memory of Zavikon was our visit in August 1954, when I was 7-years-old. My grandmother died in 1951 from a heart attack. Deeply depressed, my grandfather had no interest in being alone at Zavikon. In 1954, he invited his daughters and their families to spend the first two weeks of August with him on the island. His invitation was accepted by Ibbie, Margie and Julie; Katie preferred to summer on the Massachusetts coast. Thereafter we spent the first half of every August at Zavikon. My final visit was in 1966.

The drive from Washington, DC, to Canada, took two days and involved overnighting in Woolrich, PA. That road trip was not especially pleasurable. We were five in the car: my parents and two sisters (Debbie, 5, Cathy, 2) and I.

Cathy was a quiet baby, but Debbie was both irritable, irritating and vocal. These qualities did not make for a tranquil ride. Woolrich, which in those days was six hours distant from Washington, was the half-way point. The next morning after an early breakfast we climbed back into our 1952 Cadillac Fleetwood and headed north.

Once across the Thousand Islands Bridge, we drove to Rockport, ON in Canada, where we parked the car in a wooden garage with separate bays for about six vehicles. After locking the car and padlocking the garage door, we carried the luggage to the dock where Roy, Zavikon’s caretaker at the time, met us with “The General”, the largest, or so it seemed to me, of Zavikon’s three inboard motor launches, to ferry us to the island.

Thanks to an underwater power line from the mainland, the island had a reliable source of electricity. A back-up generator was maintained, however, just in case. My grandfather forbade the installation of telephones and television sets: we were supposed to talk with one another. A single radio in the kitchen kept the household staff entertained while they prepared the two daily meals.

The household staff consisted of three very good-natured Canadian women. Roy, and later Dick Senecal who succeeded him as caretaker, ferried them to Zavikon at 8:00 AM and returned them to the mainland at 4:00 PM. Breakfast was served at 9:15 AM and dinner at 4:00 PM. This left us six hours in the middle of the day free for activities, such as golf, tennis, or shopping in Alexandria Bay.

The days’ schedule followed a distinct rhythm. The fishermen left to fish at 5:00 AM, returning by 8:00 AM to clean their catch, which was usually pike. At 9:00 AM sharp, the grandchildren gathered in front of the door to Baba’s bedroom, which was on the second floor to the right of the main staircase. When he emerged, the grandchildren would follow him down the stairs, singing with him Old Soldiers Never Die (They Just Fade Away), a tune memorialized by General Douglas MacArthur in his farewell speech to the Congress on April 19, 1951. We grandchildren sang con brio, with greater enthusiasm than harmony.

Once the procession had descended to the living room where our parents were waiting, and after Baba had seated himself in “his” chair (that no one else ever sat in), he read the daily lesson from The Upper Room, a monthly publication of the Methodist Church. Once the reading concluded, the family entered the dining room for breakfast. Adults sat at the big table, the children at two small tables flanking the door to the porch. Grace was said and breakfast was served.

During our first years at Zavikon we were 17: Baba, three of his four daughters and their husbands, and 10 grandchildren, who in 1954, ranged in age from two to 15.

After breakfast we split up into groups; one group went to a nearby country club to play tennis, another to a nine-hole golf course with Baba, and a third to Alexandria Bay to shop. A few chose to stay on the island to read, write letters, practice the violin or flute, swim, fish off the dock, or do nothing at all.

The writers’ nook – that is, the elevated platform off the main staircase’s mid-landing – was an enormously popular venue for those who took to heart, the obligations of being a timely correspondent. It was accessible only by two short flights of steps, on either side of the table, and two straight-back chairs facing one another. The table’s drawers held paper, envelopes and ink. Most nook users brought their own ball-point pens, however. A hierarchy of users developed, and woe to him/her who flaunted seniority or protocol.

Aunt Ibbie’s daughters Julie and Cynthia, continued to hone their musical skills at Zavikon. Julie was a flutist, Cynthia played the violin. Cynthia had real talent. Over the years she taught the Suzuki Method to new generations of aspiring first violinists.

After breakfast Julie and Cynthia practiced for hours in the living room. That was reason enough to decide most of the other grandchildren to go shopping in Alexandria Bay.

Our daytime mobility depended on our fleet. We had three elegant boats. “The General,” named in honor of Douglas MacArthur, was the grandest of the three. It was a long, stiletto-shaped cruiser and was berthed in the single slip of the first boathouse, which had two bedrooms, a bathroom and a billiard table on the second floor. Over our years at Zavikon, we watched as “The General” (possibly a 27’, 1926 Ditchburn Sedan) slowly deteriorated. It was declared unseaworthy and disposed of. Pity; it cut such a trim figure, under way.

“The General” was temporarily replaced by a rented 26’ Crosby fiberglass runabout with a 35hp-outboard Johnson motor. Each one of us understood the arrival of the Crosby as a harbinger of changing times that was not necessarily an improvement on the past. Eventually, “Zavikon,” a mahogany Chris-Craft (possibly a 22’ pre-owned 1952 Sportsman) replaced the Crosby, but it could never replace “The General”.

The “fishing boat” was unnamed; everyone just called it the fishing boat. It was a 1938 side steer 26’-Hutchinson Brothers guide boat. It was built in Alexandria Bay and it was powerful and fast. One day when Baba was backing it out of its slip, he accidentally shifted into “forward” and simultaneously hit the accelerator, inflicting severe damage to the slip. The boat itself was largely unharmed. Baba never drove that boat again.

During an early morning fishing outing, Julie’s husband Charlie, a physician, entangled the fishing boat’s propeller in a thick patch of river weeds. He decided to put the engine into reverse. That way, he reasoned, the entangled propeller would simply disengage itself from the weeds. That didn’t happen. Once the engine was reversed, the now tightly ensnarled solid brass propeller simply fell off and sunk to the riverbed. A passing Canadian Fish and Game Warden kindly towed the fishing boat back to Zavikon. He cited the adults on board for multiple violations, such as fishing with invalid licenses, etc.

The river weed threat not-withstanding, the fishing boat was perfect for fishing in shallow water. It was also well suited to waterskiing and aquaplaning. The fishing boat was berthed in the second boathouse, in the left slip, as one enters the building; the “Woolrich” in the right one. The “Woolrich” may have been a 1926, 26’-Sedan, built by Hutchinson Brothers of Alexandria Bay, NY.

We also had a 12’-aluminum boat, with a 10hp-Evinrude outboard motor that we used for fishing around Zavikon. Rounding out our armada was a nondescript green canoe of no discernable pedigree, and a lovely St. Lawrence Skiff, built ca. 1912.

Most of the grandchildren, who didn’t remain on the island, went shopping. The three families took turns planning the daily menus and buying the food that the cooks would prepare. My grandfather was exempt from this duty, since he paid the staff salaries and the upkeep on the island’s facilities. The cost of fuel for the boats was also distributed among the three families.

One Alexandria Bay shopping destination for us grandchildren, was the so-called “trick shop”. This was a novelty store whose low-priced inventory consisted almost exclusively of affordable items that appealed especially to pre-teen boys: for example, itching powder, life-like rubber vomit, and genuine, made-in-China firecrackers! The shop, whose name is now long-forgotten, also sold fishing lures. I bought a red-and-white spoon (“Red Devil”) that pike never grew tired of biting on.

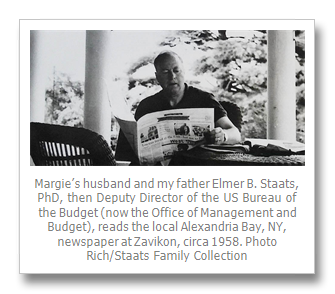

My mother and her sisters learned thrift from their parents (“Waste naught, want naught”). Each sister tried to outdo her siblings by providing the lowest cost meals. It was their game and they played it seriously. As a result, most meals at Zavikon were uninspired. Nourishing they may have been, but tasty they never were.But no one starved. This was due, in part, to the fact that Aunt Ibbie’s husband Sherry, a Methodist minister and diabetic, returned from his shopping trips with boxes of glazed and jelly donuts, a gallon or two of ice cream, cookies and other goodies that pre-teens only guiltlessly – and Uncle Sherry only vicariously – could appreciate. Uncle Sherry’s dietary supplements were greedily consumed during the evening hours when raiding the icebox was both fashionable and accepted.The shoppers collected the mail that had been forwarded to a post office box. They also bought copies of the New York Times, Wall Street Journal and the local Alexandria Bay newspaper. Newspapers were our only news sources.

Happy Hour was from 3:00 PM until 4:00 PM. Baba forbade alcohol under his roof but turned a blind eye to it at Zavikon. As mentioned, the second floor of the first boathouse had a billiard table. It also had a bar. This was the speakeasy, where cocktails were enjoyed before and after dinner. Pre-dinner cocktails were drunk in moderation. Coming to dinner tipsy could result in Baba sending the offender to bed without dinner. Post-dinner drinking, however, was much less restrained.

Smoking on the island was not permitted. Full stop. Period. Nor were the fireplaces ever lit. Baba was terrified by the thought of fire racing through the house. Fortunately, no one in our family smoked. Collapsible aluminum escape ladders that could be hung on the window sills, were part of each bedroom’s furnishings.

Even when accompanied by a parent, grandchildren under the age of ten were made to wear life jackets when not in the house. The life jackets were bright red, like fishing bobbers; the better to find a clumsy grandchild floating down the river.

The staff left immediately after the dinner serving plates and dishes were placed on the table. After dinner the family washed and put away the dishes. Later, they read or played checkers, chess or cards. Baba loved Gin Rummy. He and three others retired to the Card Room, also known as the Bottle Room. The room’s four walls were lined, floor to ceiling, with shelves of empty liquor bottles of seemingly every brand and description. This collection had been inherited from the previous owners. The Gin Rummy game was played for a penny a point, and money exchanged hands at the end of the evening.

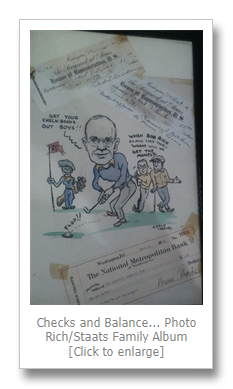

Unlike his winnings at cards, Baba insisted on receiving personal checks from those whom he defeated at golf. He never cashed the checks, but had them framed and hung them on the walls of his office, like trophy heads.

We played lots of other games. Charades were especially popular with the grandchildren and their parents. The parents organized treasure hunts, using cryptic clues that were not always easily deciphered.

Sleeping arrangements for the grandchildren were such that the boys occupied the dormitory and two of the small rooms on the third floor. The two eldest girls took the other two rooms on the other end of the floor. In between there were two full bathrooms; one for the boys, the other for the girls. Younger children slept on the second floor, the youngest with their parents. A ladder on the third floor connected to the attic, which had a trapdoor three-feet away from the attic entry. On rainy days, when we were stuck inside, we used to dive through the trapdoor onto a dormitory bed. Despite the mattress as muffler, the landings on the bedsprings were noisy and were preceded by high-pitched, excited shrieks from the divers during freefall. Having once disturbed Baba’s nap, however, attic diving was abruptly removed from the list of permitted indoor games.

Zavikon was many things to each of us; to the grandchildren, it was an agreeable setting in which to come to know one’s cousins. For most of the year our families lived very separate lives in Woolrich; (Baba; Katie and her husband Roz and their three children Charlotte, Anne and Roz Jr.); Harrisburg, Pennsylvania; (Ibbie and Sherry and their four children Julie, Sherry, Cynthia and Bobby); Lancaster, Pennsylvania; (Julie and Charlie and their three children Scotty, Bob and Charley); and Washington, DC; (Margie and Elmer and their three children David, Debbie and Cathy).

The annual two weeks at Zavikon began a process that over the years, nurtured and cemented family bonds among the Rich clan which have endured for more than half a century. For this reason, Zavikon remains a seminal experience in each of our lives that, like the old soldier of whom we sung on the staircase, some 60 years ago, never dies. Neither does it fade away.

By David Rich Staats

A former official of the US Department of Defense and the US Department of State, David Staats joined the Washington, DC-based merchant banking firm of G. William Miller & Co., Inc. in 1996, as vice-president. He became managing director in 2000. Among the many assignments on which he has worked, are mergers and acquisitions (Kuwait, Bahrain, Spain and USA); restructuring corporate debt (Turkey); business development (Russia, Germany, Qatar, Algeria, Azerbaijan, Turkey and Israel); asset management (Saudi Arabia); and mediation (USA, Germany). He also led the company-created partnership, to advise financial institutions in the US and abroad, on their compliance obligations for anti-money laundering and combating the financing of terrorism. David and his wife, Tatiana, live on the west coast of Florida.