A picture is worth a thousand words, they say, and things have stories to tell. But even if they didn’t have stories, the objects displayed in the new Chippewa Bay Maritime Museum please the eye. Through boats and decoys to painted paddles and fine art, the Museum is a great place to learn about boats and boating as well as enjoy the intersections of art, craft and history in the Thousand Islands. Here is a random selection of examples.

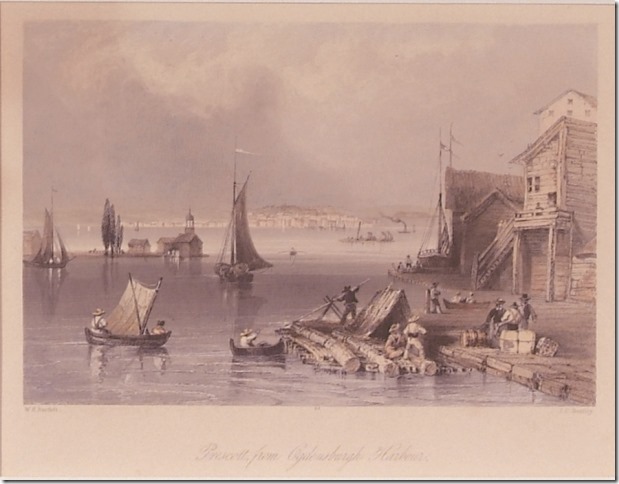

The W. H. Bartlett Print, “Prescott from Ogdensburgh Harbor,” Photo courtesy Chippewa Bay Maritime Museum

|

Many people would say that boats are still essential to really living on the River. A century and a half ago they were the only option for transportation in the region. What did they look like? How were they used? The farmers and fishers and cargo haulers didn’t leave us descriptions, and photography was still in its infancy, but we do have scores of scenes published in the popular press of the time that give us clues. These pictures are sometimes shaky on the details, but they can tell us as much about how people felt about the region as what their boats looked like.

“Prescott from Ogdensburgh Harbor” manages to document the bustling industry of the important river port in a romantic way. In the 1840s, when this image was drawn by W.H. Bartlett, Americans were proud of their growing nation, but they were also nostalgic for the peaceful and the beautiful—which, in real life, didn’t always go along with industry. In Bartlett’s Ogdensburg, the water is calm, the clouds are lovely, and folks have time to chat on the dock, but business and commerce go forward in a number of interesting boats. A steamboat near the far shore represents modern transportation—powered boats, boats that didn’t depend on the wind. Sailboats are still much in evidence, though; the one in the middle ground is headed out into the channel with a load. The log rafts, a small one in the foreground and a larger one in the channel, are the most basic of “boats” and will be broken up and the logs sold when they reach Montreal downstream. And look at the little boat with the spritsail in the left foreground—a grandmother St. Lawrence skiff.

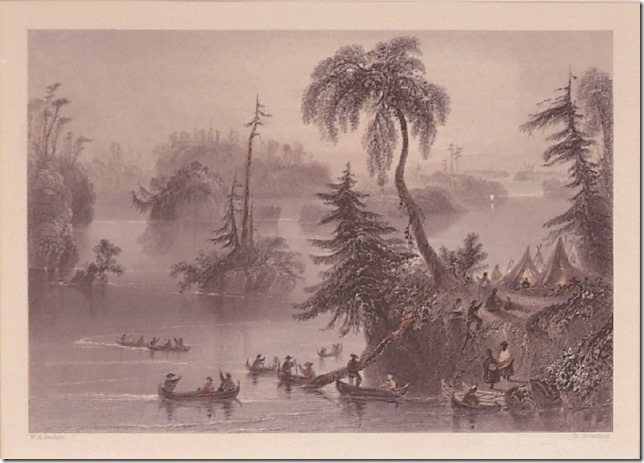

“ St. Lawrence River Scene,” drawn by W.H. Bartlett, engraved by R. Brandard. London. Published in 1839. Photo courtesy Chippewa Bay Maritime Museum

|

Bartlett seems to have been a little more fanciful in this scene along the St. Lawrence River. Wild places in America were expected to have Indians in them, but one wonders if they really looked like this. By the 1840s, eastern Indians were more romantic than scary, and Bartlett gives us romantic Indians, paddling up to their island rendezvous in big shady hats, warm wigwams waiting for them under vaguely tropical-looking trees.

Alpheus Keech

What does camping in the Thousand Islands mean to you? Is it a shingled cottage perched on a rock, or a tent on Mary Island? Your tent may not be made of white canvas, but you can share the sensations evoked by the scenes painted on these souvenir paddles a century ago by Alpheus Keech of Clayton.

Keech was a self-taught artist who made a living with his brush. His largest work was probably the magnificent eagle that adorned the paddlewheel cover of the grand steamboat St. Lawrence. From the 1890s through the 1920s he painted signs, false graining on wood, Thousand Island scenes, and hundreds of little paddles like these.

Keech had a number of themes for his paddles which he used over and over again. But each paddle in the series, whether it was “Thousand Islands Sunset,” “Camping, 1000 Islands,” a little red motorboat, or one of his general views, was painted individually by Keech. Keech carved each of the paddles by hand, as well, which kept him occupied though the long winters before the tourists arrived to buy them. You can imagine him enjoying the work with the little variations he put into each paddle. Keech sold the paddles in his shop in Clayton, and he also had a concession on one of the steamboat lines which no doubt sold plenty to people wanting to remember their week in the cool breezes and sparkling waters of the Thousand Islands.

During the long winters while Alpheus Keech was carving and painting his little paddles, dozens of other river folk were carving and painting, too. The decoy makers had a more utilitarian purpose in mind than Keech but the same artistic enjoyment of the work. The names of most are lost now. Many didn’t sign their work, and probably wouldn’t have considered themselves artists anyway—they were just carving and painting birds for their own duck-hunting rigs.

Bill Aiken and Roy Conklin

We do know about Bill Aiken of Chippewa Bay. Bill was a River man; born in Alexandria Bay, he moved to Chippewa Bay in 1933 to take over as caretaker on Oak Island. When he started carving in the 1940s his decoys were destined to be piled in bushel baskets and rowed out to a good shoal or marsh in a skiff where they were set out in groups to lure the real birds into range of the hunters. Bill was more interested in carving the forms than in painting the details, so his school chum Roy Conklin of Alexandria Bay painted most of them. Bill made over three hundred duck decoys from the 1940s through the 1960s. Where are they all now? They’ve become art objects, and they aren’t shot over out on the river. A few are featured in the Museum.

Frederic Remington

Artist Frederic Remington stayed at his Chippewa Bay camp into the fall from 1900 until not long before his death in 1909, and although he wasn’t a duck hunter, he appreciated the autumn light in the marshes where ducks could be found.

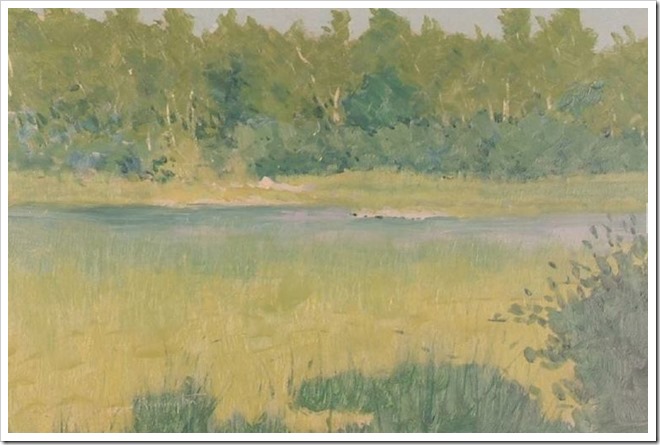

“Chippewa Marsh” by F. Remington. Photo courtesy Chippewa Bay Maritime Museum

|

Remington would arrive at his cottage off Cedar Island each year with a list of contracted illustrations for “Colliers” or other clients. He’d work steadily through the list and when he was finished, he would reward himself by fishing, boating, and painting what and how he wanted to paint for the rest of the summer.

It was in Chippewa Bay that he experimented with nocturnes and Impressionist techniques, working to shed his reputation as a “mere illustrator.” Remington painted this canvas late one summer when he’d finished his paying work. We can imagine him paddling one of his little Rushton canoes, or being rowed by his guide Pete or Larry along shore to where he could capture the golden scene.

The Chippewa Bay Maritime Museum is open Thursday through Sunday, 10-4, through August, then weekends until Columbus Day, or by appointment.

Visit chipbaymm.org for more information.

Be sure to leave time to sit on our deep porch and enjoy the breeze! |

By Hallie Bond

Hallie Bond is Curator of the CBMM. For thirty years, before she hung out her own shingle as a historian and museum consultant so she could take interesting jobs like this one, she was Curator at the Adirondack Museum in Blue Mountain Lake with responsibility for the boat collection. Her “Boats and Boating in the Adirondack” was published by the Museum and Syracuse University Press in 1995.