It’s Wednesday afternoon, at two o’clock and Mrs. Kinney, my fifth grade teacher, announces, “Those of you going to religious education may be excused.” Two-thirds of my class stands up, gathers their things, and joins the other students going to religious education on the sidewalk outside of Clayton Central School. True to life, we divide by denomination. The Protestants go their way while the rest of us scrappy Catholic kids meander down James Street until we get to St. Mary’s Catholic School and Convent where we have all attended weekly catechism class since first grade. The Sisters of the Holy Cross have been educating the Clayton Catholic youth since 1913. They wear floor-length black habits complete with white wimples, sensible black shoes and heavy wooden crosses on long dangling rosary bead necklaces around their necks. Those rosary necklaces sway back and forth, like pendulums and threaten to take out young children’s eyes as they walk down the street single file like penguins. It was the sisters’ sacred duty to put the fear of God into us, and by God, they did. With their ever-ready disciplinary rulers and penetrating looks, they drilled the prayers and rituals of Catholicism into our impressionable minds.

Despite my best efforts, I learned a lot of important things about God in catechism class through the years. For example: “Mom, Sister George told us today that God is a string bean!” This startling statement was met with a period of silence. “I think you mean God is a Supreme Being, dear,” my mother corrects me.

In 1965, the church changes everything, with the Second Vatican Council. Now the sisters can wear gray knee-length habits that show their calves and wimples that show their bangs. They can also stop taking the male names of the saints and instead take the female names. The organ is replaced with the folk guitar, and Monsignor slurs the mass in English instead of Latin while drinking the sacramental wine. The church also allows laypeople to teach us catechism. This is a huge relief because whenever the nuns tell us a Bible story, someone’s eyes get gouged out.

My catechism teacher that year is also my neighbor, Mrs. Hunt. “She’s a pretty good egg for a convert,” comments my father. I enter my classroom, take the desk next to the window, and start doing homework in my favorite subject—daydreaming. My studies are interrupted when Mrs. Hunt asks me to read Ezekiel 47:9 aloud: “There will be swarms of living things where the river flows. Where the river flows, there will be many thousands of fish because the river flows there. The salt water will be made fresh because the river flows there. Where the river flows, there will be many living things.”

After the reading, Mrs. Hunt tells us the story of the loaves and the fishes—when Jesus fed the multitudes by transforming a couple of fish into lots of fish and a few loaves of bread into many loaves of bread. Everyone goes home with their bellies full and filled with the spirit. She ends the lesson by telling us, “Children, never stop believing in miracles.”

As Mrs. Hunt is preparing us for Jesus to rise from the dead, the river is undergoing a resurrection of its own. Another winter has come and gone, and the usual tell-tale signs of spring are popping up all over Clayton: the trees bud out, the scent returns to the air, and the worms make pilgrimages across the road just because they can. Ice as thick as a man’s arm begins to melt, and at night, the floes crash into one another like carnival bumper cars.

A juggernaut of a ship with a large drill attached to its hull grinds its way through the ice on the St. Lawrence Seaway to make way for the winter-moored freighters to move their heavy cargoes from one part of the world to another. As everyone in town is preparing for Easter, my father is preparing to practice his own religion: bullhead fishing.

On the first full moon after the spring equinox, thousands of spawning bullheads will fill the creeks and tributaries of the St. Lawrence River. Bullheads will crowd one another in the water surrounding Grindstone Island and Wellesley Island and our favorite fishing spot, French Creek Bay. The bullhead is a beautiful fish. It’s got a yellow belly, a black top, whiskers like a catfish, and horns on top of its head. Carefully smooth down those horns when pulling your hook out of its mouth or the horns will poke you and fill your palm with poison. A bullhead has no scales on its skin, and in the spring, their flesh is tender and sweet. The only time of year you want to eat a bullhead is in the spring because they are bottom feeders. When spring turns to summer, the water along the shore and the bullhead’s flaky, tender, sweet meat gets muddy.

The bullhead is sorely in need of orthodontia. They have an unsightly underbite that allows them to scoop worms into their mouths. Bullheads don’t pluck a worm off a hook just dangling in the water. They lurk in the cool shadows of the creek and wait for their food to come to them, and when it does, they open their mouths and scoop the ball of worms, concealing the hook in their mouths, and they’re yours.

The full moon after the spring equinox is on a Thursday that year. Of us five kids, only my sister Mary and I want to go fishing with Dad. He tells us we’re in charge of the worms. A soft rain has fallen earlier that evening, perfect for nightcrawlin’. When it’s dark, Mary grabs the flashlight. I can’t find my shoes. She runs out the door ahead of me and goes over to the Marshalls’ backyard. They’ve got the best mud pit filled with the longest, plumpest, juiciest, biggest worms in the world. She’s way ahead of me and over by the stink bomb tree when I stand on something hard and round. Oh my gosh, this is the biggest worm in the world. No, no, it’s not a worm. It’s a snake, probably just a garter snake. Wait, it’s not a garter snake. It’s a rattlesnake. We don’t have rattlesnakes around here, but I’m sure this is one. No, it’s a cobra. Oh my gosh, what if it’s not a cobra? What if it’s an anaconda or a boa constrictor? “Mary, Mary,” I whisper. She runs back, disgusted with me. “Hurry up, slowpoke.” “I’m standing on a snake. If I move even the tiniest bit, it will eat me alive,” I whimper. She points the flashlight at my toes. “You’re standing on a garden hose, stupid.” We gently stretch fat, thick worms out of the earth and put them into a coffee can with wet shredded newspapers in it so they don’t dry out. Once it’s full, we take it home and put it by the car Dad has packed with everything else we need to go bullheading: bamboo poles, a Coleman gas lantern, a ratty pink quilt to sit on, a picnic basket with butter, bologna, and cheese sandwiches wrapped in wax paper, a jug of Kool-Aid, and a flask of something else to help my father “slake his thirst.” The full moon is rising, and it’s time to get in the car. Dad drives through town, turns right on Cape Road, then left onto Frontenac Springs, and another left onto Crystal Springs.

The pavement gives way to gravel. The moon is shining so brightly Dad turns off the lights. The rocks in the road sparkle and lead us to French Creek. Mary and I are laughing in the back. “Open your mouth and close your eyes,” Mary tells me. “Nuh-uh, you’re gonna spit in my mouth like you did at the drivein movie the last time,” I say. “I am not. Now close your eyes and open your mouth. I got a surprise for ya.” “No way! You’re gonna spit in my mouth!” “No, I’m not. I got a piece of candy for ya, but I’m only gonna give it to ya if you close your eyes and open your mouth.”“You got candy?” Mary knows I’ll do anything for a piece of candy. You know, worms don’t taste as bad as you might think.

Dad turns around. “Stop your yappin’; the fish will hear you.” We quiet down and listen to the rocks pop under the tires. Dad turns off the engine at the top of the grassy knoll, and we gather our things quietly and click the doors shut so we can surprise the fish. Our feet are soon soaked as we walk down the dewy grass to the creek. Dad lays out the blanket, poles, worms, picnic basket, and lantern. We sit silently looking at the moon’s reflection in the black water. Off in the distance, we hear our neighbor’s tires popping on the gravel as they drive in the moonlit darkness to the creek.

It doesn’t take long before ten or more blankets are spread alongside ours. No one says a word. The smells of Kool-Aid and whiskey mix in the air. The hiss of the Coleman lanterns, the sound of unwrapping wax paper, and the mosquito’s high-pitched zzzzz is followed by the sound of hands slapping skin. Then, when the moon is high above us, we hear the sound we have been waiting for: bullheads are spawning down the creek. There are so many of them that their tails flap against one another as they rush forward into the narrowing water. Everyone jumps up and grabs a pole. As soon as the ball of worms hits the water, a bullhead grabs it and is yanked to shore. It doesn’t take long for our picnic basket to be full, and we are home and asleep in our beds by one o’clock.

The next day in school, Mary and I are so tired we rub our eyes, but we know we have so much to look forward to that night. There’s an all-you-can-eat Friday night fish fry dinner at the fireman’s hall. It costs five bucks a head, and kids under twelve get in free. Plates piled with bullhead are waiting for us. As soon as we finish one, we raise our hand and a fireman brings us another. The only other food on the table is a loaf of bread. Mrs. Hunt is sitting at our table. I yell to her, “Mrs. Hunt, this is just like the story of the loaves and the fishes!” She hollers back, “Regina, life is a miracle!”

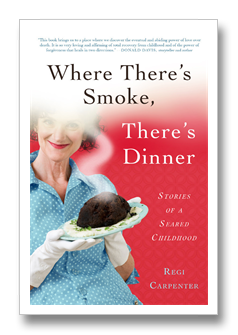

| Award-winning storyteller and performer Regi Carpenter brings her humor and honesty to print in Where There's Smoke, There's Dinner: stories of a seared childhood. Now available on Amazon.com Regi is the youngest daughter in a family that pulsates with contradictions: religious and raucous, tender but terrible, unfortunate yet irrepressible. These honest tales, some hilarious, some heartbreaking, celebrate the glorious and gut-wrenching lives of four generations of Carpenters raised on the Saint Lawrence River, in Clayton, New York. From teenagers struggling to find their identity, to disabled veterans grappling, with the aftermath of war, and change to the complications and sweetness of love between family members, this collection of linked short stories holds the universal message that life's difficulties are softened by love and fortitude . . . and family." Available now on Amazon.com |

By Regi Carpenter

Regi Carpenter is a solo performance artist, short story writer, and performance coach, who grew up in Clayton, NY. She holds a BFA from Ithaca College, where she currently teaches storytelling. She has toured her solo shows and workshops in theatre, festivals and schools and her writings and blogs have been published in several print and online publications. Regi is the recipient of several awards including the J.J. Reneaux Emerging Artist Award, a Leonard Bernstein Teaching Fellowship Award, the Parent's Choice Gold Award, the Parents' Guide to Children's Media Award and the Storytelling World Award. Her performance piece Snap! won the 2012 Boston Story Slam. Snap! is a featured Listen story on The Moth website. She lives in Ithaca, New York.

Last November Regi did a TedxTalk called "A Hush in the Room." In it, she shared her experience with death, love, grief and storytelling. Since that time she has gotten more involved in the power of storytelling and witnessing to help express and understand grief in adults and children. You may watch her TedxTalk here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ceCq_wF8GlA