It was the last of summer when I came upon an old torn piece of lined yellow paper:

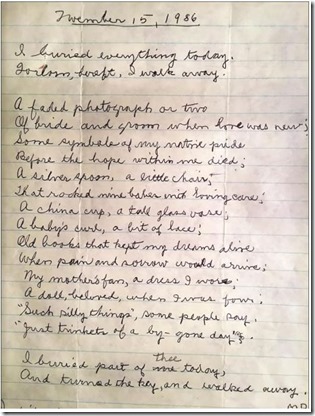

| | November 15, 1986 I buried everything today. Forlorn, bereft I walked away. A faded photograph or two Of bride and groom when love was new; Some symbols of my native pride Before the hope within me died; A silver spoon, a little chair That rocked nine babes with loving care; A china cup, a tall glass vase; A baby’s curl, a bit of lace; Old books that kept my dreams alive When pain and sorrow would arrive; My mother’s fan, a dress I wore; A doll, beloved, when I was four; 'Such silly things,' some people say. 'Just trinkets of a by-gone day.' I buried part of me today, And turned the key, and walked away. MDH |  | |

It was a poem written by my maternal step grandmother, Mae Deck Hiatt, of Lincoln, Nebraska. Was it worth saving? Well, I thought so. I put it aside to frame and hang on a wall.

It was one of thousands of pieces of paper, cards, news stories, magazines, bank records (golly, do I need to shred them), drawings, paintings, photo albums, photos framed, photos unframed, school records of ancestors I never knew, grocery lists, lists of guests, lists of many things found in box after box after box in our attic. Books, furniture, skis and skates, vinyl records and record players, ancient televisions, parts of boats, works of art, bits of fabric saved for quilt-making, cupboards of clothes saved for who knows what. War trunks. War letters. Scrapbooks by year and envelopes of more awaiting a transfer to scrapbooks that never took place.

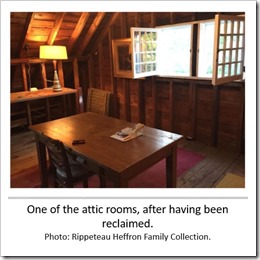

The seemingly endless personal belongings of my forebears had ended up one way or another in the attic of the 1907 family house that we now owned on Wellesley Island. And all I wanted to do was to clean it out. Beneath all of the clutter, there was, I knew, a glorious attic with wood framing, stone chimneys, a high peaked ceiling and a couple of semi-finished rooms, an attic just waiting to be revealed and enjoyed. I wanted it back.

I had worked on this project sporadically every summer since we had taken ownership in 2000. One autumn, a childhood friend came to help me. She rolled her eyes coming upon notes and cards exchanged between her own mother and mine. ‘Jane, you cannot keep all this stuff,’ she said, dropping handfuls into a waste bin.

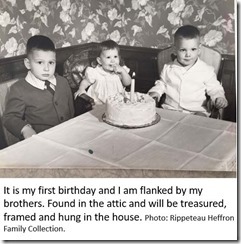

I had started in earnest again in the dying days of last summer. The urgency fell upon me for one reason: the death in Florida the prior spring of my cherished father, who had lived to the age of 99. This family event had precipitated another round of dispersal of family goods, more papers, more emotive items, more treasures that tug upon the heart strings. My brothers and I had sorted; even so, much came straight to the capacious attic of our house. The additional clutter was more than I could bear. I put on what I hoped would be my final push to reclaim the attic.

I had started in earnest again in the dying days of last summer. The urgency fell upon me for one reason: the death in Florida the prior spring of my cherished father, who had lived to the age of 99. This family event had precipitated another round of dispersal of family goods, more papers, more emotive items, more treasures that tug upon the heart strings. My brothers and I had sorted; even so, much came straight to the capacious attic of our house. The additional clutter was more than I could bear. I put on what I hoped would be my final push to reclaim the attic.

We all know the glory days of September on the River, 70s and sunny by day, refreshing and chilly by night. Last September, on perhaps the most spectacular of one of those days ever to occur, I had spent the day in the attic on my sorting project. I knew it was a spectacular day because I kept looking out at it through the numerous attic windows. I could catch sight of friends racing by in their boats.

At last, I went downstairs, got cleaned up and headed off to an end-of-season party on the Lake of the Isles, on the other side of Wellesley. As always, there was an abundance of food, wine and all the usual friends. The sun was beginning its set-piece descent across the water, sending its golden highway over the River to the docks on shore and up the lawn that rose to the cabin. I saw a perfect seat on the porch next to Thom, a lifelong friend. We and our siblings had all grown up together in Watertown.

It was then that I heard about the box of string too short to save.

Various friends had regaled me over the years with how they had dealt with their own attics and house clearings. One had opened up the attic windows at his home and shoved stuff out over the roof to a dumpster below. Tad Clark had cornered me with a question: do you know how many barge loads it took to get the junk off Comfort (the Victorian house in his family since 1883, until recently sold)? “Twenty-two,” he had said, with triumph. The new owner had hired a barge to move it all from island to shore; among the bags would have been items mentioned in Tad’s 2015 book, “Comfort Island, One Family’s Generational Journey.” The moveable treasures of great uncle Alson Skinner Clark, the American impressionist, (that is, the ones not painted as murals directly on the walls of the house) had already been saved.

But the best stories came from Thom. He had listened as we sat and sipped wine and I blew off steam over missing the great day because of my attic project. I was wrung out from dust and memories. Soon I was chuckling as he recounted how it had fallen to him and his sister to empty their family’s large house in Watertown. They came upon some 2,000 color photographic slides taken by their mother. “It wasn’t that she was such a good photographer,” said Thom. “It was just that she had taken them. We couldn't bear to throw them out.”

But the best stories came from Thom. He had listened as we sat and sipped wine and I blew off steam over missing the great day because of my attic project. I was wrung out from dust and memories. Soon I was chuckling as he recounted how it had fallen to him and his sister to empty their family’s large house in Watertown. They came upon some 2,000 color photographic slides taken by their mother. “It wasn’t that she was such a good photographer,” said Thom. “It was just that she had taken them. We couldn't bear to throw them out.”

Boy did that ring a bell: couldn’t bear to throw out. The two of them had rented a light table and spent three days bent over the horde, sorting it for dispersal among the siblings. Thom remembered standing at the front door directing hired men carrying out loads to piles: dump, donate, save.

At a relative’s house he also cleared, Thom came upon a hall closet. “I opened it,” he said. “It was stuffed from bottom to top with smoothed out folded up paper bags, presumably from Watertown grocery trips when everything used to be packed in brown paper bags and recycling was a concept yet to be. Another treasure soon turned up. “There was this box,” said Thom. He had brushed it off to read the top, ‘”It said: ‘string too short to save.’ It was written right there on top. I opened it up and there were all these tiny little short pieces of string laid out straight.”

We both understood. We’d both grown up in post-war households. Ours was also a string and aluminium foil-saving home. My parents had survived the Dust Bowl, the Depression and the Second World War. Who was I to complain about washing off, flattening out and replacing the piece of foil for future use? It might be needed! The people of that era, the ones Tom Brokaw called the “greatest generation,” never easily threw things away.

But why had I not opened the attic windows to a dumpster and saved myself time? Why had I set myself this laborious task of triage: save, donate, discard? The motivation was complicated. As Thom, I could not bear to just throw out. It all tugged the heart strings too much. And of course there is the intrigue: just what is inside all these boxes, envelopes, albums, trunks, closets.

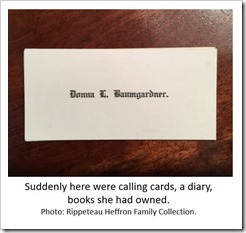

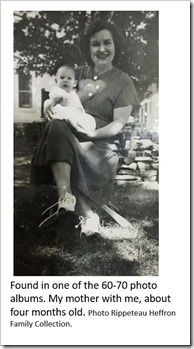

But there is another layer, isn’t there. These collections are the stuff of lives lived. They are the detailed content, the partial record of a life. As I opened manila envelope after manila envelope, each marked by its year, and pulled out my mother’s lists and notes and letters, it was as though my mother was there, standing there, beside me. It was an incredible thing. She was showing me how she had lived her life, what she did, what she cared about, how she kept track of things, what she wanted to remember, a life, precious, valued. It had been nearly 28 years since her death, yet I often missed her intensely and these discoveries had the comforting effect of bringing me closer to her once again.

We all know the acquire-and-tire problem of the attic. We acquire. We tire. The attic fills. We’ve lost interest, or the items have broken or gone out of fashion. Rather than dealing with decisions ourselves, we put them out of sight and leave them behind. Our kids grow up, leave home and their stuff gets boxed for a later retrieval that never occurs. The boxes of string too short to save, and everything else, become somebody else’s future problem.

The parental and ancestral hoard in my attic was typical in its range from mundane to profound. Guest and grocery lists for my mother’s bang-up post-war parties, not forgetting one ever after known in our family as ‘Queen passing-by day’ when Elizabeth II sailed her yacht “Britannia” up the channel, past our house, these mingled with signed notes from US presidents and statesmen.

Memorabilia from a Nixon inaugural ball sat with study papers from a one-room rural school house; my mother used to ride her pony to get there. I came upon my own school papers, from grade school and high school in Watertown. Looking through them, I was moved by the depth and scope of the education I had received in our local schools. There were piles of family photographs from rural Nebraska, some dating from the time photography was new. In one box was an image labelled with the name of my great great aunt and her two closest childhood friends: Evelene Brodstone, later Lady Vestey of the British meat empire, and the American author Willa Cather.

I came upon the diary of a young girl in love; it was the hand of the grandmother I had never known and of whom, all my life, I had had virtually no prior evidence at all. She had been a kind of mythic mystery, having died giving birth to my mother, on a remote Nebraska farm, in February 1917, as a savage snow storm raged. The horseback doctor did not get there in time. And then, too, there were the collections: the plates, the spoons, the hats, and not forgetting a half century of cook books that illuminated a changing America.

It was when I was digging into the lower half of the very last box that I came upon the poem with which this piece begins. Had I not persevered, I would not have it. Right there in front of me, with the economy of poetry, it summed up the entire process in which I had been so engaged.

So, is the string too short to save?

I thought about the mass of contents that I had diligently considered and triaged. Was it really just the detritus of a life’s minutiae? Or was it the evidence of lives lived and valued too greatly by their owners to simply throw away.

By Jane Rippeteau Heffron

© Copyright Jane Rippeteau Heffron 2017, All Rights Reserved

The author was born and raised in Watertown, NY, spending summers in the Thousand Islands. She graduated from the University of Rochester and then earned a MSc degree at Columbia University’s Graduate School of Journalism. She was a reporter for The Washington Post in Washington, DC, prior to joining Business Week magazine in New York City. When she and her husband moved to England, she joined the Financial Times, and later ran a publishing department for investment research at Citigroup. The family has a home on Wellesley Island and Jane is a board trustee of the Thousand Islands Land Trust.