So far my articles have concentrated on the winners with increasing populations over the last four decades. Now I will mention the losers. Even though birds are better understood and monitored than most other living organisms, our knowledge of many species remains crude and imprecise. Only when species are rapidly increasing or severely declining can we detect significant population fluctuations. For species in decline such understanding may come too late to stop local or regional extinctions of a permanent or temporary nature. For the following birds a clear decline has occurred in our region during the last forty years.

Black Tern. This diminutive "marsh tern" was well distributed here and there along the River as a breeder in the late 1970s. Since then it has virtually disappeared from the area remaining only at two sites near the River. This local pattern mirrors a regional decline in the northeastern quarter of the continent. Our remaining largest population is at Perch River Wildlife Management area with its controlled water levels. It is likely the hydrological disruption of previous water level management on the River has contributed to this species decline. Hopefully, the adoption of Plan 2014 will gradually make our marshes more hospitable to this lovely bird.

The Loggerhead Shrike was once a fairly common bird in Northern New York. This species was already in decline, by the 1970s and was virtually extinct in New York, by a decade later. We haven't a clue why, as its habitat seems intact. This decline has occurred throughout most of the northern parts of these species range, where they are migrants.

The late Dr. F. G. Scheider of Syracuse, suggested our birds were vulnerable to chemical control of fire ants, on their winter range. This seems as good an explanation as any. The province of Ontario has begun a restoration effort for this species, by releasing captive reared birds. Perhaps some of these will expand to our area, or a similar effort that may be undertaken in New York, will help restore this interesting predatory songbird.

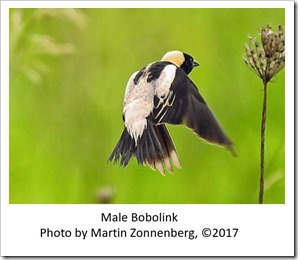

The group of birds that has declined the most in our region, during the last four decades, are those that utilize grasslands. Intensive agriculture is the primary culprit, by converting grass to row crops and by doing too frequent mowing of remaining grass areas. Thus, species breeding in these areas are being hammered at a level, where reproductive success is often impossible. The populations of species, such as the Eastern Meadowlark, Bobolink and Savannah Sparrow, have been reduced. While these birds still remain fairly common locally, the trend is not a positive one.

Other species, including Northern Harrier, take months to get their young to fledging. The constant mowing has rendered, once suitable nesting areas, unusable. The Upland Sandpiper (formerly called Upland Plover) and Henslow's Sparrow, once fairly Common in our region, are virtually gone. The North Country Bird Club has existed for seven decades and their newsletter is called the Upland Plover. This indicates how common this species once was, as bird club newsletter mascots are usually locally common birds of interest. The current editor of that publication tells me he has never seen the species in the field in NNY.

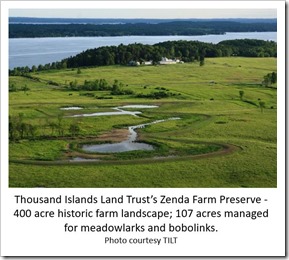

Grassland birds, in general now, require human conservation action, such as that being conducted by the Thousand Islands Land Trust. This avian guild is one of the fastest declining bird groups in many parts of the world. Grassland birds are in severe trouble, for many reasons, possibly including climate change. They will require concerted conservation management efforts, such as those that improved Bald Eagle and Common Tern populations in our region. Their future locally depends on us.

One of the poster children for bird decline in North America, is the Golden-winged Warbler. A candidate for the federal endangered species, this species was not common in our region, four decades ago. The gradual shifting north of this beautiful bird is a result of competitive pressure, from the closely related and genetically dominant, Blue-winged Warbler. These two species were once geographically isolated, but have been brought together by landscape level changes,due to human activity. Scientists are scrambling madly, to understand breeding habitat factors that may isolate these two species. One of the two largest Golden-winged Warbler populations, in the Northeast US, now exists in the nearby Indian River Lakes Region. Management efforts are underway, to understand how best to protect and manage this species in our region. Hopefully success will occur, as there is a limit to how far north this species can retreat, before it runs out of suitable habitat.

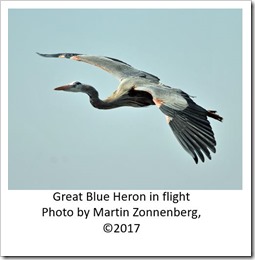

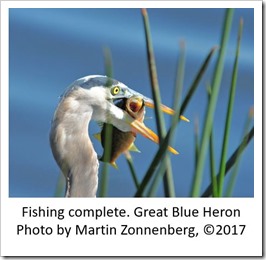

Several other birds that were more common on the River, forty years ago, are experiencing local and regional declines, from known and unknown factors. Great Blue Heron sightings, in the Thousand Islands region, have decreased in this century. This is in large part due to the abandonment of the massive Ironsides Island colony. Cyclic colony development and abandonment is normal for this species, due to nest tree die-off and other factors. Many of the herons from this colony seemed to have formed smaller associations in other areas. It's unclear if this apparent decline is real, or simply an artifact of smaller more dispersed colonies. This species seems to be doing well in most parts of New York State.

For human residents with bird feeders, the decline of one species of winter visitor is striking. The Evening Grosbeak used to descend in hordes on any available sunflower seed, prior to the mid-1990s. This species was an incredibly common winter visitor, for the first three decades of my birding career. Then suddenly, over just a few short years, the hordes came no more. By this century, the sighting of pairs and small groups became an event. Why? Well it appears that over the last few years, science has given us an answer to the enigma. While they are with us, these big bold finches are vegetarians, inhaling sunflower seeds, like vacuum cleaners.

t turns out that while on their Canadian Forest breeding grounds, a primary food source is the spruce budworm, whose tiny caterpillars infest black spruce. When infestations develop,populations surge along, with those of several Warbler species, including Cape May and Bay-breasted. It seems that there have been fewer cyclic outbreaks of the budworm, in the last two decades and those that have occurred have often been suppressed, by commercial forestry interests. This species population seems to be exhibiting evidence of a slight rebound, but whether the hordes that graced my youth will return in my lifetime is unknown.

Bird and wildlife populations are dynamic and fluctuations with change are normal. Unfortunately, given the intense pressure humans are placing on our planet, wildlife is being forced to adapt much faster than evolution usually requires. For those that do, they shall remain our fellow travelers in life for a long time. As the dominant species on this planet, we must assure that the losers, in the brave new world of the Anthropocene, are part of the future of the Thousand Islands.

By Gerry Smith

Gerald A. "Gerry" Smith, is an ornithologist who can often be found leading fellow bird enthusiasts, on guided Thousand Islands Trust (TILT) tours, throughout the year. He is a graduate of the biology program at SUNY Oswego, is one of the founding members of Derby Hill Bird Observatory, along Lake Ontario. He was the first staff ornithologist at Derby Hill, for the Onondaga Audubon Society. Gerry was President of the Onondaga Audubon Society and in 2010, he published the popular guide book, "Birding the Great Lakes Seaway Trail.”