In the early nineteenth century, the world’s fancy was captured by the sport of competitive rowing. By the 1870’s, it was common for competitors from Australia, Great Britain, Canada and the United States to travel great distances to race. Public attention was frenzied. Thousands, and even tens of thousands, of spectators were reported to have turned out to witness rowing events. The prizes and awards were spectacular. Race promoters solicited investors to contribute to large monetary purses. Other valuables such as sterling silver trophy cups, gold watches, and even boats and oars were offered. One trophy award was a sixteen-ounce sterling silver belt manufactured by Tiffany and Company.

Behind the public acclaim and the prize moneys, a voracious gambling network was thriving. An individual racer might be rewarded with gambling kickbacks from syndicates and from individual winners, offers of free meals and lodging, and fame! There were established rules. Referees were on hand to judge the competition, but many accounts question the referee decisions which decidedly favored the home team or the gambler’s choice. “In the 19th century, rowing had a very dark side. Cheating, interference, throwing and fixing races, damaging equipment, poisoning, and threats of death were known to occur.” 1

The public response was indeed enthusiastic. In 1869, a competition between Harvard and Oxford in London was covered by fifty American reporters, who traveled to the banks of the Thames River. Oxford carried the day by six seconds. The front page of “The New York Times” was filled with their reports. Suddenly all across America, racing fever raged. Boat clubs had existed before this time, but now rowing clubs were springing up at dozens of American colleges, and fierce competitions ensued.

The sport seeped into the popular culture of the world. Rowing magazines were published. Sheet music and songs with rowing themes were popular. The champions of the rowing world were featured on carte-de-visite cards which were sold at regattas.

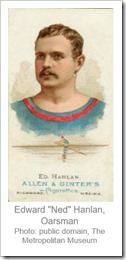

Works of art depicted rowing competitions. The English painter, Thomas Eakins, produced a large body of work featuring racers and race scenes. Currier and Ives produced racing images in prints. In 1887, a tobacco company from Virginia, Allen and Ginter, issued the first set of sport cards as cigarette premiums. Ten professional oarsmen were honored. Other tobacco companies jumped on board. The W. S. Kimball and Co. cigarette company and Murad Tobacco offered collectable silks and felt patches featuring the collegiate teams. Later embossed leather patches were produced.

Out of this world of athletes , who were the “heroes” of our story?

Out of this world of athletes , who were the “heroes” of our story?

Edward “Ned” Hanlan, known as “The Boy in Blue” for the color of his attire, was The World Champion. He was Canadian, hailing from Toronto. Hanlan was a powerful oarsman and pioneered the sliding seat scull, but he was a man full of nasty shenanigans and misdeeds on the race course. He did not enter our race at Westminster Park, but remember his name; you will hear it in our story.

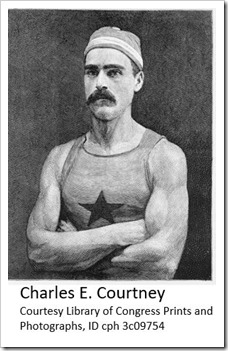

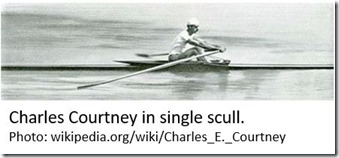

Charles Edward Courtney, from Union Springs, New York was a carpenter by trade. He rowed as an amateur and won over 88 races with no losses. In 1877, Courtney became a professional oarsman, but he found himself in a world of controversy over racing ethics. He suffered a painful loss to Ned Hanlan in 1878 and a charge of race fixing. What developed was more than a simple grudge.

In one race at Lake Chautauqua, Courtney awoke on race day to find his scull sawed in half. In an 1877 race against James H. Riley, Courtney was unable to race due to drinking poisoned ice tea at his pre-race dinner. The allegation was that an unscrupulous innkeeper with a large bet on the race was to blame.

Such was the world of professional racing. More bitter rivalries ensued. Courtney had a checkered reputation but his skillful technique overcame that and he went on to coach the crew team at Cornell University. Character issues followed him throughout his life.

James H. Riley, a hotelier from Saratoga, New York, was a champion single sculler. He seemed to have escaped many of the unpleasant controversies in the racing world, but raced with some mighty oarsmen and had many distinguished victories.

James A. Ten Eyck, who hailed from Tompkins Cove, New York, was another oarsman of renown. Ten Eyck coached the team at the United States Naval Academy and later at Syracuse University. The Intercollegiate Rowing Association Regatta named a trophy after him. Syracuse fans will recognize the name of the crew boathouse at the inlet of Onondaga Lake: the James Ten Eyck Memorial Boathouse.

How did these giants of crew racing happen to come to the Thousand Islands in 1882? First, some local history….

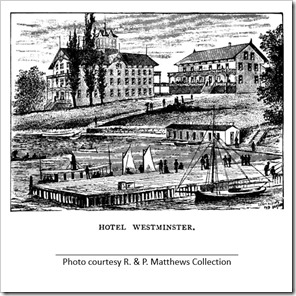

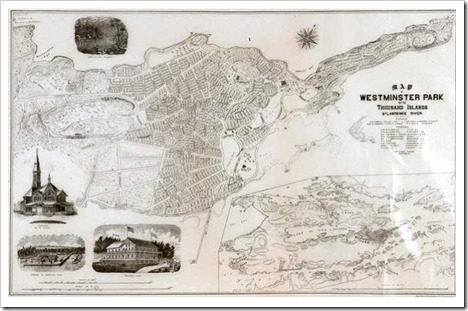

In 1875, a group of Presbyterians formed a stock company to build a religious resort on the foot of Wells Island (Wellesley Island). Over the next several years, a summer community known as Westminster Park was developed. It featured a hotel, a boarding house, a magnificent chapel, and many cottages, as well as recreational facilities.

In 1881 the Harrington Brothers took over the hotel management from the first proprietor, R. F. Steele. Customers were courted from near and far by glowing accounts published in area newspapers and in fashionable magazines. The Harrington Brothers published a tourism pamphlet (as had Mr. Steele in 1878) extolling the virtues of the area and the facilities offered in Westminster Park. The Harrington Brothers enlarged, refitted, refurnished and repainted the hotel adding forty rooms, new baths, new sanitation systems, and even new Segar Improved Spring Beds, “than which no better is made”. There were “billiard rooms with new Collender tables, a splendid bowling alley, barber shop, new room, circulating library, etc. etc.” 2

Amusements offered included enjoying commanding views over 500 acres of hill and dale, grassy lawns, shady groves and pleasant walks to dedicated picnic spots. The waters offered the best fishing in close proximity to the Hotel, with boats for hire and competent oarsman and guides available. The Hotel maintained a horse livery, with carriages and saddle horses. Religious services were not mentioned in these advertising brochures, but many came for services in the community.

Hotel patrons could travel by a network of trains: N. Y. Central, Utica and Black River Railroad, Rome, Watertown & Ogdensburg R. R., and the D. L. & W. R. R. Research shows us that many of the Park founders had financial interests in these new rail systems, as well as in the local hotels. Passengers arriving at River ports were carried to the island on various steamboat lines. One such boat was the “New Island Wanderer” owned by Captain Visger of Alexandria Bay. Captain Visger himself had worked on the development of Westminster Park. His crews had built the long dock on the American channel side, the warehouse/sitting room, and fourteen miles of roads when the Park was being developed. Another steamer, “The Island Belle”, was to make several trips from Cape Vincent to the Park on Race Day.

What we see is a group of business entrepreneurs that had heavily invested in the Westminster Park community and the transportation to get there. With a short summer season, it was critical to attract customers. Unfortunately, 1882 saw the beginnings of a financial recession in America. This recession was to continue for three years and was to become one of America’s most depressed business cycles. Attracting customers to the network of railroads, steamship lines, and hotels was key to survival of these institutions.

What we see is a group of business entrepreneurs that had heavily invested in the Westminster Park community and the transportation to get there. With a short summer season, it was critical to attract customers. Unfortunately, 1882 saw the beginnings of a financial recession in America. This recession was to continue for three years and was to become one of America’s most depressed business cycles. Attracting customers to the network of railroads, steamship lines, and hotels was key to survival of these institutions.

Could this have been the motivation behind sponsoring such a glamorous event as The Great Race of 1882? Or had the Harrington Brothers simply caught Crew Race Fever?

From the “Oswego Morning Express” September 8, 1882, we read that a prize purse of one thousand dollars was raised by “the Thousand Islands House, the Westminster Park Hotel, the Saint Lawrence Hotel, citizens, and others.” ( As race day approached, newspapers report large hotels in the Bay backed out. The purse was raised solely by Westminster Park and St. Lawrence Hotel proprietors. )These men arranged for three of America’s greatest oarsmen, Charles E. Courtney, James H. Riley and James A. Ten Eyck, to compete in a rowing race on the waters of Poplar Bay. The purse offered $750, for first place, and $250 for second. A special purse of $300 was offered by the proprietors of the Westminster Park Hotel and the Saint Lawrence Hotel to the oarsman beating the best record time. (And those were 1882 dollars!)

Excitement was generated by the newspaper world. Railways planned excursion packages, with discounted rates for round trip fare s and one week’s board, at the Westminster Hotel. A Watertown train excursion featured musical entertainment by The City Band. Mr. W. S. McKean, agent for the Richelieu and Ontario steamboat company, announced excursions that would run from all points up and down the River. Mr. R. Asa Packer II offered his steam yacht for use by the referees. Spectators began to arrive, many staying a number of days to witness the celebration and the boat race. Race promoters hashed out contracts and rules of the race. Arrangements were made for “an efficient police force to maintain good order to be hired.”3 Preparations for the largest gathering ever on the banks of the River were being made.

s and one week’s board, at the Westminster Hotel. A Watertown train excursion featured musical entertainment by The City Band. Mr. W. S. McKean, agent for the Richelieu and Ontario steamboat company, announced excursions that would run from all points up and down the River. Mr. R. Asa Packer II offered his steam yacht for use by the referees. Spectators began to arrive, many staying a number of days to witness the celebration and the boat race. Race promoters hashed out contracts and rules of the race. Arrangements were made for “an efficient police force to maintain good order to be hired.”3 Preparations for the largest gathering ever on the banks of the River were being made.

Enter the contestants! Staying at the Westminster Park Hotel were Charles E. Courtney and Mr. Brockway, his brother-in-law/agent. Courtney’s workouts were conducted in the Canadian Channel. Newspapers recounted an amusing story told by Mr. Courtney about a practice run down the Lake of the Isles:

Enter the contestants! Staying at the Westminster Park Hotel were Charles E. Courtney and Mr. Brockway, his brother-in-law/agent. Courtney’s workouts were conducted in the Canadian Channel. Newspapers recounted an amusing story told by Mr. Courtney about a practice run down the Lake of the Isles:

“Rowing along close to the shore, he (Courtney) was hailed by some farmers on an island, one of whom inquired his name. ‘My name is HANLAN!’, equivocated the oarsman, thinking that the men were Canadians, and of course friends of Hanlan. ‘Well,’ said the inquisitive farmer, ’you may just bet your boots that Courtney will beat you like blazes next Monday.’ ” 4

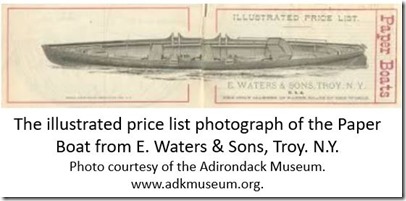

Courtney rowed a paper shell that was 30 1/2 feet long and 11 inches broad and weighed 29 pounds. The patent for paper sculls was held by George Waters of Waters and Sons, Troy, NY. The process involved molding a paper skin of manila paper treated with varnish over a mold to dry and then building a wooden framework to fit the skin. Rowers were very keen to protect their equipment and Courtney kept his under lock and key when it was stored at Westminster Park.

Ten Eyck and his trainer ( his brother Frank) stayed at the Saint Lawrence Hotel in Alexandria Bay. His boat was reported to be similar in design to Courtney’s. Ten Eyck was in top physical condition. His practice runs were taken in the American Channel.

The race course was determined to be three miles long with one turn. The starting line was directly in front of the Westminster Park Hotel. The course went out to a buoy near Rockport, Ontario. These waters are fairly protected from all winds but the Northeasterlies. Frank Hinds, a well-known surveyor, measured out the course and Courtney helped Hinds to set the buoys. ( We might note that in 1878 Frank Hinds had worked on the development of Westminster Park as the surveyor laying out the roads and lots, and it was he who drafted the iconic map of Westminster Park [See above].) It was the perfect course for the Westminster Hotel guests as over half of the windows of the Westminster Hotel offered a commanding view of the course.

The fanfare continued. Newspapers reported crowds of hundreds and thousands of spectators were expected to gather to see America’s greatest oarsmen. To sweeten the excitement, a new challenge arose. The idea of a race in Saint Lawrence skiffs developed. This race would be held after the scull competition. Courtney offered $100 toward a purse to race against Ten Eyck, John Hoadley and William Shepherd. Hoadley and Shepherd were well-regarded oarsmen from Alexandria Bay. Local friends offered an additional $100.

Finally, race day arrived. Monday, September 18, 1882! Crowds were fewer than anticipated. James Riley was a scratch; he did not appear in Westminster Park for this race. Rumors of other great race names coming to town ran through the crowds. A last-minute entry of James Dempsey was telegraphed in. Mr. Dempsey, a blacksmith from Geneva, NY, arrived in time to practice on the course before the main event. He and Courtney were reported to “have had trouble” before. These grudge matches helped to fuel the excitement of the races.

Race time approached. Quiet waters of a late afternoon made for a smooth race. Amid fanfare, Courtney, Ten Eyck and Dempsey completed the course. Charles Courtney handily won the scull race. I found no report of the skiff race.

Although it was not the extravaganza hoped for, I am sure there was a profit to the hoteliers, railways and steamship lines. Most likely the gamblers went off with full pockets and the crowds enjoyed a chance to see some of the mighty champions of the sport.

Westminster Park may have established its reputation as a worthy vacation spot, but the race went down as a small footnote in scull racing history.

Endnotes: - Friends of Rowing History: The Wild and Crazy Professionals by Bill Miller

- Harrington Brothers, “Summering at Westminster Park of the Thousand Islands, River St. Lawrence”, Alexandria Bay, New York, 1882

- Watertown Times, 11 September 1882

- Watertown Times, 09 September 1882

References: - Geneva Courier, 01 April 1883

- Harrington Brothers, “Summering at Westminster Park of the Thousand Islands, River St. Lawrence”, Alexandria Bay, New York, 1882

- Oswego Morning Express, 08 September 1882

- Pulaski Democrat, 21 September 1882

- Watertown Times, 07 September 1882, 11 September 1882, 16 September 1882

- Wikipedia, Depression of 1882-1885, Charles E. Courtney, James A. Ten Eyck

Websites: |

By Linda Twichell, Copyright 2017 All Rights Reserved

Linda Lewis Twichell, a fifty-four year resident of Westminster Park, has collected stories of the Westminster community since the 1970’s. In 2016, Linda and Leigh Charron Smith collaborated on “Westminster Park; A Tapestry of Tales”, a multi-media presentation shown at the Cornwall Brothers Museum, Alexandria Bay and at the Jefferson County Genealogy Society, Watertown. A book of Westminster Park, its people, and their stories is in the works.