The water, after six decades, remains silenced.

This year marks the sixtieth anniversary of the completion of the St. Lawrence Seaway. Built to create a more efficient shipping route into the North American industrial heartland and to harness the River’s full hydro-electric generating potential, the scale of the project was unprecedented.

On July 1st, 1958, an explosion of earthen dams raised waters along a fifty kilometer stretch of the River, west of Cornwall, completing a project that displaced thousands of Riverside residents and destroyed their communities. A wild and historic River, lost.

II

My grandfather, Irwin Coulthart, captured images of that place and era. The changes wrought by the Seaway were of great interest to him. His ancestors lived within earshot of the Long Sault Rapids, and after the completion of the Seaway he and his wife Mildred acquired a property along the newly-formed waterfront, a farm field they turned into a cottage lot with no small amount of effort.

He spoke with equal fascination of the River as it had been, with its thunderous whitewater, and of the River, it became during the Seaway’s construction, when those same rapids were drained and silenced and the River’s bed lay open, a rock garden for all to explore. In 1955, my grandfather bought a slide camera. Many of his images—taken on family day trips—portray the River before and during its transformation. They leave us with an amateur’s view of a River, altered by forces stronger than its defining waters, and a personal record of a disappearing Riverscape.

III

|

Photo courtesy Stevenson Family Collection

|

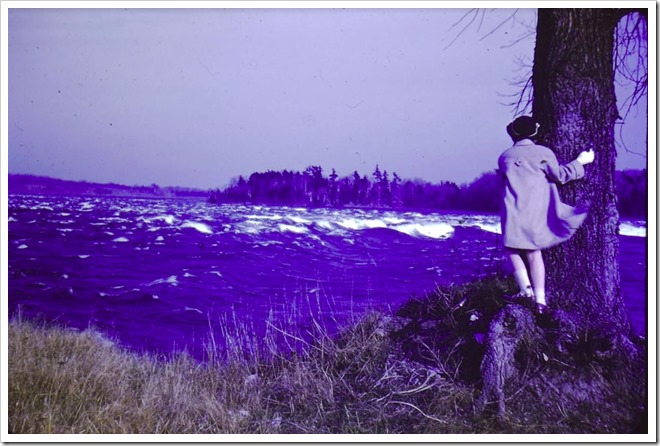

April 1955: My mother Elaine looks out over the Long Sault Rapids near Dickinson’s Landing, Ontario. She recalls being intimidated by the heavy whitewater in front of her.

Here we see the rapids at the height of their power—an impression made fuller by the low perspective from which the photograph is taken. The potential and the problem of the rapids are apparent. Their flow represents an opportunity to capture the draining hydraulic force of the Great Lakes watershed, and an obstacle to a seamless nautical route to the continent’s interior.

Three years later, inundation erases this scene from view.

IV

|

Photo courtesy Stevenson Family Collection

|

Spring 1955: Seen from Sheek’s Island, the Canada Steamship Lines Beaverton heads up the Cornwall Canal and past the village of Milles Roches. The canal and its locks allow ships to bypass the sixty-foot drop of the Long Sault Rapids.

The Beaverton is a “canaller”—a class of boat whose size is limited by the dimension of locks built more than half a century earlier. Their carrying capacity is not equal to the task of servicing a post-war economy growing vastly in scale.

Milles Roches will be flooded, and its residents and some dwellings relocated to “New Town #2”, one of a pair of newly-planned communities, a few kilometres to the west. It is later named formally as Long Sault, Ontario.

V

|

Photo courtesy Stevenson Family Collection

|

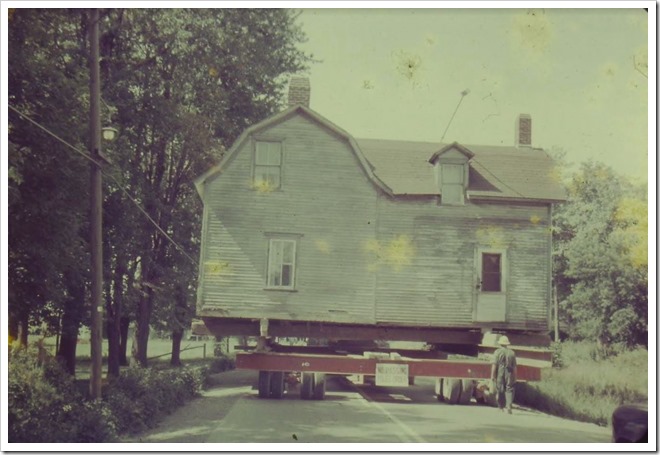

August 1956: A house is moved westward, along Highway 2, from Milles Roches to Long Sault.

Project officials negotiated with local residents, to either purchase their homes or to give them the option of having their houses moved to one of the new communities.

Houses being moved—their interior possessions left intact—are raised onto moving frames, pulled to their new locations and settled on modern foundations. Each is given an identifying number plate, with many hooked-up to modern plumbing for the first time.

The spectacle of house moving, signals that the alteration of the landscape is an impending reality.

VI

|

Photo courtesy Stevenson Family Collection

|

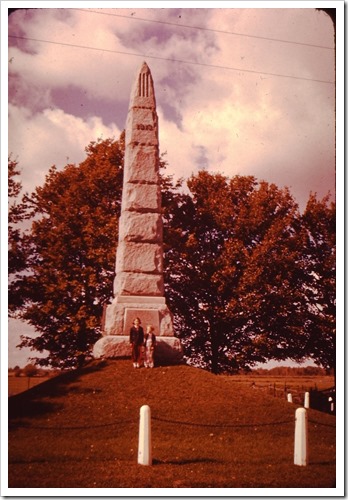

Autumn 1955: My mother Elaine (on the left) and aunt Diane stand in front of the monument that marks the location of the Battle of Crysler’s Farm of November 11th, 1813, when British soldiers and Canadian militiamen disrupted an American force descending the St. Lawrence in an attempt to capture Montreal.

The monument is located a stone’s throw from the river, between Morrisburg and Aultsville. It is later placed on a much larger mound slightly downriver at Upper Canada Village, where the Ontario government relocates some historically significant buildings that would have otherwise been destroyed by the project.

Also located at Upper Canada Village is a memorial garden dedicated to the riverside cemeteries that will be flooded. Into the garden’s walls are embedded headstones from graves that will be sealed with cement. Visiting the headstones of his ancestors becomes a pilgrimage of sorts for my grandfather in his later years.

VII

|

Photo courtesy Stevenson Family Collection

|

May 1957: A family trip to visit the Riverbed of the Long Sault Rapids; perched atop a rock are my mother and my aunt. My grandmother stands behind them, flanked by family friends accompanying them on the occasion.

This section of the River is diverted and drained between April and December 1957, and becomes a site of frequent visitation. The bottom reveals a jumble of rock, arranged by millennia of immense water power and perfectly-rounded holes, where small rocks had drilled through softer sections of stone. A pair of these rocks, labelled and dated accordingly, come home as souvenirs of this trip.

VIII

|

Photo courtesy Stevenson Family Collection

|

May 1957: The same outing, with the view looking north to the Canadian shoreline. The party is obscured by slabs of rock. Behind them, the exhaust from the stack of the Canadian Steamship Lines Simcoe drifts over the River. Overlooking both canal and whitewater, the rise of land beyond the canal wall had long offered a dramatic view of passing ships and steamboats descending the rapids.

IX

|

Photo courtesy Stevenson Family Collection

|

Summer 1957: West of Cornwall, the Moses-Saunders Generating Station takes shape. The dam rises above a River, now diverted from its natural course; temporary “cofferdams” protect the building site from the redirected waters. The intricacies of engineering a new River course, on such a scale, fit with the mid-century sentiment that science can overcome any natural obstacle.

The family group here includes my grandfather’s brother, Eldred, standing with hands in pockets and staring intently at the construction scene. An engineer himself, he is perhaps most interested in the technical complexities before him.

X

Aside from a couple of occasions, when projector and screen were set up for a basement showing, these photographs sat for decades in their plastic trays, untouched. I appreciate them as a blend of people familiar and gone, captured in happy family moments. But they are more than simply that.

On the diamond jubilee of an era fading from view, they give us personal moments, captured on the central stage of a broader historical drama, glimpses of places about to be submerged. Places that live on in memory and image, even if it is impossible to visit them ever again.By Craig Irwin Stevenson

Craig Irwin Stevenson grew up in Cornwall, Ontario, and spent an inordinate amount of time on and along the River, at his maternal grandparents’ cottage on Moulinette Island, the easternmost of seventeen islands created by the Seaway flooding. He is a history teacher at Tagwi Secondary School, in Avonmore, Ontario, and never misses a chance to tell his students that the River they see today was once a very different place.