Patriot Chronicles: What the British Did with Their Prisoners

Written by John C. Carter posted on February 13, 2018 12:48

On the morning of July 21, 1928, residents of Oswego, New York awoke to find the former convict ship Success, moored in their harbour. One can only image what their thoughts might have been! The Success was not there to pick up political prisoners, but instead it was touring as a convict museum and stopping at various ports on the Great Lakes. After a 30-day visit to Rochester she sailed to Oswego, and was open there as an exhibit to the public for ten days.

Touted as being older than “Old Ironsides” (an erroneous claim), the Success had been constructed in 1840. It was first used as a merchant ship, and then provided transport for emigrants moving to Australia. Later, she was purchased by the State of Victoria and used as a prison hulk. In 1890, the Success was refitted as a museum ship whose purpose was to travel the world advertising “the horrors of the convict era.” After a period of time in Sydney, New South Wales, she sailed to England and in 1912, crossed the Atlantic to tour the eastern seaboard of the United States. She was featured at the Panama-Pacific International Exhibition of 1915, in San Francisco, and at the Chicago World’s Fair in 1933. In the interim, the Success sailed the Great Lakes, eventually docking at Oswego in July of 1928.*

Background:

In England, in the eighteenth and nineteenth century, the desire to remove criminals from society, the cost of operating prisons, the value of incarceration, as a means of punishment and reform, and finding an alternative to capital punishment, were all matters of concern. To alleviate massive overcrowding in British prisons and prison hulks, felons were transported to various locations including colonies in Africa, the West Indies, Bermuda, Gibraltar, Malta, Australia and North America. After the 1776 War of Independence, the option of sending prisoners to United States ended. In part, this resulted in more convicts being sent to New South Wales and Van Diemen’s Land.** Here is where the connection was formed between Canada/United States and political prisoners convicted for their involvement in the 1838 Rebellions in Upper and Lower Canada.

The Rebellions:

During 1838, rebellion broke out again both in Upper and Lower Canada. In Upper Canada, between December 1837 and December 1838, at least fourteen armed incursions from United States occurred and were recorded. Over 1,090 men were arrested for piratical invasion, insurrection or treason. Of those tried and convicted, 92 English speaking participants were transported to Van Diemen’s Land as political prisoners. These men were captured at the St. Clair Raids, the Short Hills incursion, the Battle of the Windmill, and the Battle of Windsor. A total of 58 French speaking prisoners, who were involved in events associated with the Lower Canada Rebellion, also faced the same fate. They all received a one way ticket to Australian penal colonies aboard British convict ships. They were sent from one continent to another aboard three different vessels, the Marquis of Hastings, the Canton and H.M.S. Buffalo.

The Marquis of Hastings:

Members of the Patriot Forces, who were captured at the Short Hills incursion in the Niagara Region, were tried and convicted and then sent to England, to be put on trial again. After these proceedings ended, thirteen were ordered to be transported to Van Diemen’s Land. Nine of these men were put on board the Marquis of Hastings, commonly known as “a Bay ship.” It sailed out of Portsmouth Harbour on March 17, 1839, along with 240 other male convicts. This 452-ton merchantman was under charter to the convict service and had made three previous voyages to Van Diemen’s Land, loaded with prisoners. By 1839, measures to ensure the humane treatment of those on board had been mandated. The concern for health, schooling and catechism replaced previous evils associated with transportation of an earlier period, but these measures were not enough to overcome the human misery of a long and hazardous journey and over-crowded confinement.

Benjamin Wait was the only known Canadian prisoner to write and publish about the journey. He detailed the infestations of lice and cockroaches, and summarized the conditions aboard: “You will say this picture is disgusting; but if the relation is revolting to the mind, what sensations must have been engendered by a participation in reality? Ah, many nights did I spend, without sleep or rest, while my ever busy mind would roam the wide world without motive, and assume a tone, but little short of distraction – when every noise was hushed, save the lashing of the waves against the ship’s sides, the creaking of the helm, the occasional tread of the crew on deck, or the heavy breathings of human beings about me, has my heart experienced every vicissitude of human misery and passion – sorrow and grief, gloom and despondency, anger and the extreme of despair endured to an extent seldom felt by man.”

Putting aside such personal sufferings, the ship fared well with continued dry and fine weather, until passing the Cape of Good Hope. After entering into the Indian Ocean, both the sailing and medical conditions worsened. Wait wrote about what he experienced; “...we found high winds, rough seas, and foggy weather; where, in a night squall, we lost our jib-boom, and dropped the foreyard, both of which were soon replaced, and we passed on safely, although many fears were entertained for the rickety old craft. Notwithstanding many high gales, she proved a safe conveyance to us.” The Marquis of Hastings finally arrived in Hobart Town on July 23, 1839, after a voyage of 128 days. The Surgeon Superintendent, Edward Jeffery, recorded that; “A school was established in the prison [ship] and about 40 of the prisoners, who at the time of coming aboard merely knew their letters, can read and write tolerably well on the Ship’s arrival in the Colony. Divine service was performed every Sunday and every means [were] used to promote a religious and moral disposition in the convicts. The greatest attention was paid to their cleanliness.”

In the August 2, 1839 edition of the Hobart Town Advertiser, the following was written: “The Canadian Prisoners” – Nine of these unfortunate men have arrived...We believe there is every disposition on the part of the Local Government to treat them as leniently as possible.” Time would tell whether this pronouncement would become an actuality.

The Canton:

On September 13, 1839, Surgeon Superintendent John Irvine went aboard the hulk Leviathan at Deptford, England, and inspected the incarcerated men who were to be embarked to Van Diemen’s Land, on the 507-ton Canton. A total of 240 convicts, including the four remaining North American prisoners, would sail from Spithead on September 22, 1839. A Short Hills prisoner, Linus Miller, wrote about his experiences. Apparently there was resentment of the political prisoners and their privileges by the rest of the ship’s felon population. Miller noted: “The most horrible blasphemy and disgusting obscenity, from daylight in the morning till ten o’clock at night, were, without one moment’s cessation, ringing in my ears. The general conversation of these wretched men, related to crimes of which they professed to have been guilty, and he whose life had been most iniquitous was esteemed the best man. I tried to close my ears and shut my eyes against them all, but found this a difficult task.”

Exactly seven weeks after departure, the Canton made an unexpected stop at the remote Island of Tristan de Cunha in the South Pacific. There a supply of fresh beef was picked up. Throughout the long voyage, the overall health of the prisoners was good. John Irvine noted that only two men had died and that; “Nothing further occurred during the voyage worth relating. The general health of the convicts remained throughout better than I could possibly have expected...The weather in general during the voyage was extremely good and with the exception of about three weeks in the tropics the temperature was mild and general.”

After sailing for 112 days, the Canton anchored in Hobart Town, Van Diemen’s Land, on January 12, 1840. Irvine reported that; “Sir John Franklin the Lt. Gov. of V.D.L. and the Col. Sec. [Colonial Secretary] were pleased to express their certain approbation of the cleanliness of the Canton and to my arrangements in regard to the comfort and health of the convicts under my superintendence and also of their personal cleanliness and healthy appearance on their disembarkation.” Irvine must have been pleased, as payment to contractors depended upon the number of convicts “delivered” alive. It was therefore beneficial for the ship’s captain and surgeon to keep the convicts healthy and not have them die on the voyage.

Local newspapers specifically noted the arrival of the Patriot prisoners. The [Hobart Town] Colonial Times of January 14 said; “The Canadian rebels (so termed) have arrived by the Canton. They are men, we learn, of good property, and respectability, and are to be free, as regards this Colony, so soon as they land.” This was not to happen! In the January 17 edition of the Tasmanian Weekly Dispatch, another interesting observation and pledge was made: “By the Canton have arrived four Canadian state prisoners...All four were implicated in the insurrection in Upper Canada...They are to be worked like common convicts – they are to be treated like common thieves. At least, we believe there is no order to the contrary. Our desire being to serve these unhappy men, not to injure them by injudicious interference, we abstain from saying what we think of this order of justice, until we are better acquainted with the particulars respecting them. In the meantime, we desire it to be understood, that any advice or assistance in our power, we shall be happy to render them in their distress.”

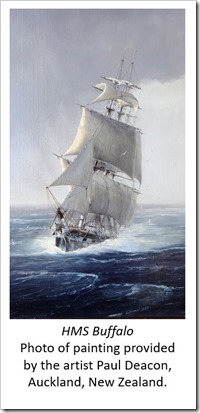

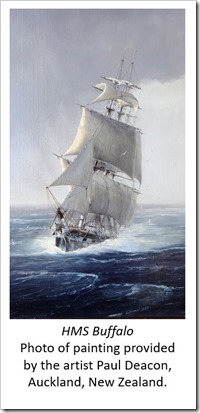

H.M.S. Buffalo:

While the Marquis of Hastings and the Canton had sailed from England to Van Diemen’s Land, H.M.S Buffalo began its journey to the penal colony from Quebec City. The 79 Upper Canadian prisoners were taken there from Fort Henry by canal boat, and then on the steamer King William. They were joined at Quebec by 58 French speaking prisoners from Lower Canada. The Buffalo departed on September 28, 1839. Captain James Wood confirmed the Buffalo’s destination, and the prisoners’ ultimate fate: “It appears by a Warrant from His Excellency Sir George Arthur that the Prisoners from Upper Canada are under the sentence of Transportation for Van Diemens Land, which Warrant requires me to convey them thither.” While the Marquis of Hastings and the Canton had sailed from England to Van Diemen’s Land, H.M.S Buffalo began its journey to the penal colony from Quebec City. The 79 Upper Canadian prisoners were taken there from Fort Henry by canal boat, and then on the steamer King William. They were joined at Quebec by 58 French speaking prisoners from Lower Canada. The Buffalo departed on September 28, 1839. Captain James Wood confirmed the Buffalo’s destination, and the prisoners’ ultimate fate: “It appears by a Warrant from His Excellency Sir George Arthur that the Prisoners from Upper Canada are under the sentence of Transportation for Van Diemens Land, which Warrant requires me to convey them thither.”

On September 29, Lower Canadian prisoner Benjamin Mott, wrote the following to his wife Almira; “I must inform you that we are on board the ship Buffalo, and about three hundred miles below Quebec, with a fair wind. My health has been tolerably good since I left Montreal...The time that we were sent for, we know not; whether we shall go to England or not, I cannot tell.” *** For the most part, the voyage was uneventful. On October 12, it was reported that the rebels had “...formed a conspiracy to murder the ship’s crew, but fortunately it was discovered in time. They were saved, and the ship’s company and soldiers have been day and night under arms.” On October 19, the ship log recorded the death of Asa Priest, who was then buried at sea. With only one stop on November 30, 1839 at Rio de Janeiro, to re-provision ship supplies, the Buffalo arrived off Hobart Town on February 11, 1840. This voyage had taken 137 days and traversed over 16,000 miles. On February 13, civil authorities went on board, to take descriptions of the convicts who would be landed there. However, they were not landed and taken to the prisoners’ barracks, as usual, but were eventually put ashore at New Town Bay. Then they were sent directly to the Sandy Bay Probation Station. Here they began their public works on the roads. On February 26, the Buffalo left Hobart Town for Sydney, where on March 9, the 58 Lower Canadian prisoners were unloaded. ****

Conclusion:

This signaled the end of what has been described by historian Mary Milne McRae as “...the last group of convicts to be transported from Canada, and the largest body of non-English convicts to come to Australia in the transportation period.” These events constituted a small but important part of British penal heritage, as well as becoming chapters in the histories of United States, Canada and Australia.

End notes:

*By 1930, it was claimed that 21 million people had visited this attraction. The Success continued to dock at ports, as a museum ship until 1945, when it became unseaworthy. It was towed to Sandusky, Ohio, and then moved nearby to Port Clinton to be scrapped. There on July 4, 1946 a fire broke out and she was totally destroyed.

**From 1812 until 1853, convict ships were sent directly to Van Diemen’s Land. During this fifty year-period, an estimated 76,000 convicts (including 13,683 females and 3,000 former soldiers) arrived in the penal colony. They were transported in over 300 convict ships. Men and women were transported separately, on their own vessels. This system ended in 1853, and soon after Van Diemen’s Land was officially renamed Tasmania. Today it is one of the states of Australia.

***Benjamin Mott, a farmer from Alburg, Vermont, was captured during the uprisings in Lower Canada at Lacolle, on November 7, 1838. He was transported, with the French speaking prisoners, on the Buffalo, but did not land in Hobart Town. Instead he went on to New South Wales, and was unloaded at the Lonbottom Stockade, Parrametta, along with the other 57 Lower Canadian prisoners. Mott returned to Van Diemen’s Land aboard the Waterlily, in February of 1844, after having applied to be with the English-speaking Patriots. During his ticket of leave, he worked in Hobart Town for the American consul, Elijah Hathaway. He received his free pardon on January 14, 1845, and eventually returned to Alburg, after a seven-year absence.

****After dropping off the Lower Canadian prisoners in Sydney, the Buffalo journeyed on to New Zealand to pick up a load of timber. She arrived at the Bay of Islands on April 4, 1840, and then sailed to Cooks Bay off Mercury Island on May 5. The Buffalo was destroyed by a severe gale on July 28, 1840 at Whitianga.

|

Bibliography/Suggested Reading:

Charles Bateson. The Convict Ships (Glasgow: Brown, Son & Ferguson, 1959).

Charles Cozens. Adventures of a Guardsman (London: Richard Bentley, 1848)

+William Gates. Recollections of Life in Van Diemen’s Land (Lockport, N.Y.: D.S. Crandall, 1850).

Giles Harrison, “A Chapter on the Patriot War,” in Abby Maria Hemenway (ed.). The Vermont Historical Gazetteer (Burlington, Vt.: A.M. Hemenway, 1871), v. 2

+Daniel D. Heustis. Narrative of the Adventures and Sufferings of Captain Daniel D. Heustis (Boston: Redding & Co., 1847).

Phillip J. Hilton. ‘Branded D on the Left Side’: A Study of Former Soldiers and Marines Transported to Van Diemen’s Land, 1804 – 1854, Ph.D. thesis, University of Tasmania (2010).

Patricia Kennedy, “Seeking suitable punishments,” The Archivist (May/June, 1988), v. 15, # 3.

+Caleb Lyon (ed.). Narrative and Recollections of Van Diemen’s Land, During a Three Year Captivity of Stephen S. Wright ((New York: New World Press, 1844).

+Robert Marsh. Seven Years of My Life, or Narrative of a Patriot Exile (Buffalo: Saxon & Stevens, 1848).

Mary Milne McRae, “Yankees From King Arthur’s Court: A brief study of North American Political Prisoners transported from Canada to Van Diemen’s Land,” Tasmanian Research Association Papers and Proceedings (1972).

+Linus B. Miller. Notes of an Exile in Van Diemen’s Land (Freedonia, N.Y.: W. McKinstry & Co., 1846).

n.a. “Banishment. How England Has Disposed of Her Convicts,” Brooklyn Eagle (April 20, 1888).

n.a. “Convict Ship to Arrive in Oswego Today,” The Ogdensburg Republican-Journal (July 31, 1928).

n.a. The History of the Convict Ship Success and the dramatic story of some of the prisoners of the convict ship (Cleveland, Ohio: Jantzen Printing, 1929)

n.a. “Torture Devices of the Old Convict Ships,” Modern Mechanics & Inventions (September, 1930).

n.a. “Transportation Versus the Hulks,” Hobart Town Advertiser (October 1, 1841).

n.a. “The Transported Political Offenders,” Melbourne Times (May 6, 1843).

n.a. “Treatment of Convicts on Board the Hulks,” Sydney Morning Herald (August 29, 1843).

James Rees, “Horrors of a Prison Ship,” United States Military Magazine (1840/41), v. 2.

Maree Ring, “Convict Ships to Van Diemen’s Land: Was There Leisure or Pleasure?” Tasmanian Historical Research Association Papers & Proceedings (June, 2002), v. 49, # 2.

Stuart D. Scott. To The Outskirts of Habitable Creation (New York: iUniverse, 2004).

+Samuel Snow. The Exile’s Return (Cleveland: Smead & Cowles, 1846).

+Benjamin Wait. Letter From Van Diemen’s Land (Buffalo: A.W. Wilgus, 1843).

Brad Williams, “The archaeological potential of colonial prison hulks: The Tasmanian case study,” Bulletin of the Australasian Institute for Maritime Archaeology (2005).

+ firsthand accounts of Patriot exiles who made the sea voyage to Van Diemen’s Land

|

By Dr. John C. Carter

Dr. John C. Carter is a Research Associate, History & Classics Programme, School of Humanities, University of Tasmania, and is a frequent contributor to Thousand Islands Life. The author would like to thank Tom Fenton, Sue Karakyriakos, Pat Kennedy, Maree Ring, and Dr. Stuart Scott for their input in writing this article. Their assistance is much appreciated.

This is Dr. Carter’s 16th article in the series: Patriot Chronicles. A treasure trove of history.

Posted in: History, Places

Please feel free to leave comments about this article using the form below. Comments are moderated and we do not accept comments that contain links. As per our privacy policy, your email address will not be shared and is inaccessible even to us. For general comments, please email the editor.

Comments

Comment by: Tom Fenton

Left at: 11:17 AM Thursday, February 15, 2018

Very informative article, and very readable. I discovered a part of history of which I knew nothing except through the imprisonment and transportation of my 3rd great grandfather, Benjamin Mott. Thank you, Dr. Carter, for filling in voids in my family and British, Canadian, and Australian history.

Comment by: Katy Thomas

Left at: 12:40 PM Thursday, February 15, 2018

Very interesting. It seems to be common knowledge that Australia was settled as a penal colony, but I never thought much more about it. You've given major insight into that process. Thanks for the article.

Comment by: Paul Smith

Left at: 6:04 AM Saturday, February 17, 2018

I enjoyed reading this article about so much history in the area which I grew up in and still reside to this day. Thanks for sharing.

Comment by: Terry Hicks

Left at: 1:40 PM Tuesday, February 20, 2018

As the GGGG-Grandson of the Patriot War participant, Garrett Hicks, I am pleased to read such well researched articles such as Dr. Carter's. While my Grandfathers' intentions are unknown to me, he was an interesting character, though I see no proof he inbibed too much during this adventure, as the author of Guns across the River postulated in his book. He may have done so, however serious research in the U.S., Canada, Tasmania and England does not back it up as far as I have found. So, good on Dr. Carter for his source citing for all 16 of his articles on the subject. Terry Hicks, La Crosse, WI USA

Comment by: Ian Coristine

Left at: 3:26 AM Thursday, February 22, 2018

Thank you for the interesting education John.

|