I

Through the St. Lawrence Seaway story, runs a current of movement that goes beyond water.

It is a story of rising water, of rebuilding, and of migration. A story of riverside residents, picking up their homes, lives and memories, and relocating along a River that bore little semblance to the one they had known.

This new River imposed a visibly different shape upon its surroundings—the shape of new towns that replaced lost villages, of road and rail abandoned and rebuilt, of islands submerged and new ones emerging from heights of land.

For all that, the Seaway remains as a grand project of 1950s-era growth, it is also a story that is the sum of its many personal connections.

|

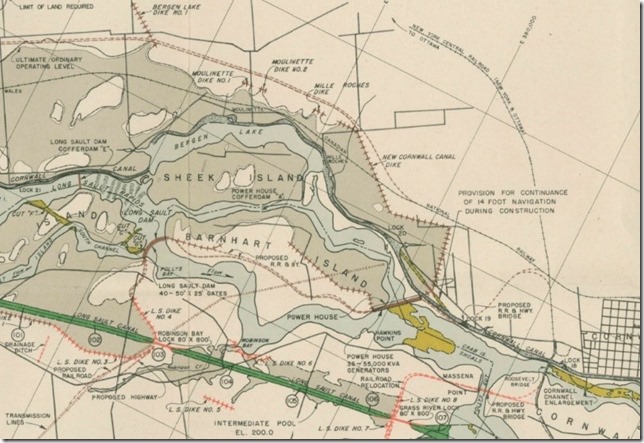

Detail of 1954 Seaway Project blueprint

|

II

After the American Revolution, my maternal grandfather’s ancestors settled on Sheek’s Island, along the famed Long Sault Rapids.

My great-grandfather, David Coulthart, built a cottage there, late in his life. When Seaway construction commenced, he had to abandon it. Too old to rebuild on a new island that would be created with the raising of the River, he passed the opportunity to his son Irwin, then the vice-principal of Cornwall’s high school.

My grandfather picked a lot, from the map of an engineer, who warned him that there was no certainty as to where the property’s lines would fall, once the floodwaters were raised.

These are his images, taken before and during the Seaway’s construction. They comprise a visual record of transition, of a tumultuous period in history, when modernity overtook a River, and those who lived along it.

III

|

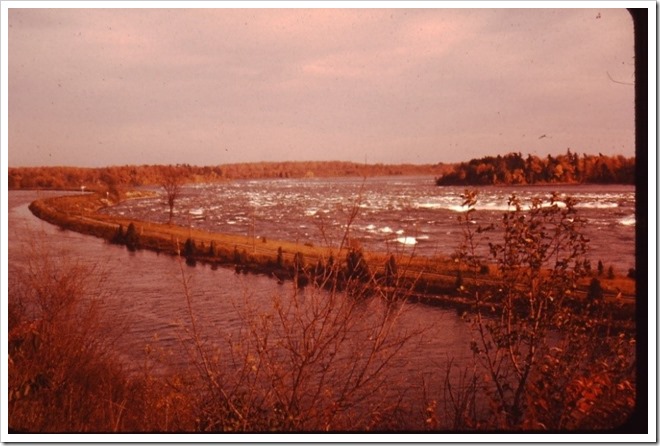

September 1955. An autumn scene at the head of the Long Sault Rapids, and a view that had drawn spectators for decades.

|

Here, the River’s dual character is on full display. On the right, it is still wild, and drops swiftly to form the Long Sault Rapids. North of the rapids, the River has been diverted to suit human needs, with the elevated Cornwall Canal, calm by comparison.

In appearance and in substance, they make for a remarkable contrast: the order of human control, against the River’s force and flow.

In 1955, they exist in balance, but change is imminent.

IV

|

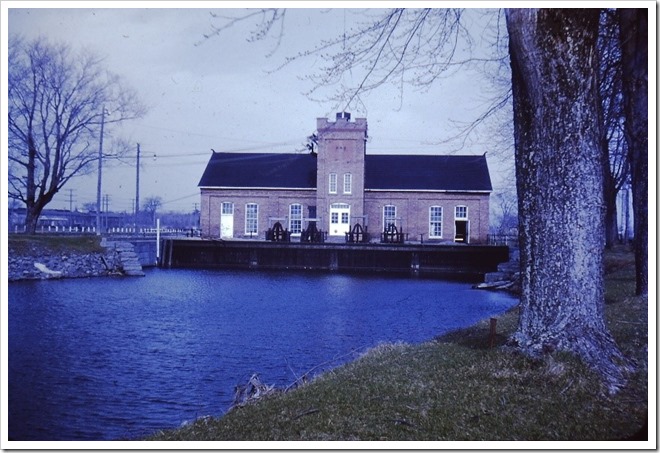

May 1955. At the tail of Sheek’s Island, a channel cuts away from the Cornwall Canal and leads to a powerhouse that generates electricity for the canal’s lights and local industry.

|

The powerhouse, completed in 1901, operates under the ownership of the St. Lawrence Power Company. With its tall windows and squared central tower, it characterizes the Edwardian architecture of the period.

This is the future that eventually births the Seaway. The generative potential of the River is, by mid-century, matched by a high level of industrial demand, in the expanding post-war economy. Facilities like this can serve small-scale needs, but cannot meet the requirements of industrial giants, like Reynolds Aluminum or ALCOA, both located on the American side of the River near Massena, New York.

Before inundation, the powerhouse structure is destroyed. Its gates and tailrace lie intact, in thirty, to sixty feet of water, and are now popular scuba diving sites.

V

|

April 1955. My mother Elaine Coulthart (closest) and her sister Diane watch the Canada Steamship Lines “Simcoe” head down the Cornwall Canal. They are standing atop the wall that separates the canal from the river, with the rapids immediately behind them.

|

This scene represents a scale of commercial transportation, about to disappear from the St. Lawrence. Like the Sheek’s powerhouse, is the future waiting to be reborn. The Seaway—as its name implies—will recreate the River, as a more direct shipping route between the Atlantic Ocean and the Great Lakes. No more will commercial interests be forced to forward freight around the rapids and through winding canals, via small canallers like the “Simcoe.”

And as the Seaway does away with the original canal system, so too does it render obsolete, an entire class of ships. Most will be scrapped, soon after the Seaway’s opening.

The fate of the Simcoe differs. It is given the honour of being the first ship to enter the new Seaway system, when it officially opens in 1959, and is later converted for use as a gas drilling platform on Lake Erie.

VI

|

Winter, 1956. My mother leans on a tree at Ault Park on Sheek’s Island, silhouetted against the Long Sault Rapids.

|

Located at the head of the island, the park offers a full view of the rapids. It is named after Levi Addison Ault, who grew up in nearby Milles Roches, made a fortune as an industrialist in Cincinnati, and donated this piece of his family’s land, as an act of philanthropy.

Seen from this angle, the high riverbank, in the background, shows how millennia of powerful flow had carved out the River’s course. With inundation, these high banks will disappear, between Iroquois and Cornwall.

VII

|

March, 1956. East of Dickinson’s Landing, Ontario, a tower-and-cable system has been erected across the Long Sault Rapids.

|

Buckets, running along the cable, release stone and ground into the River, to form a cofferdam that will stop the flow of water down the rapids. This will divert the River away from the building site, of the Moses-Saunders hydro-electrical dam downstream.

To the right of this view—just out of sight—a channel has been cut, through Long Sault Island. It will carry the River’s flow—and it, in turn, will be manipulated to allow the Long Sault control dam to be built in two separate stages.

In a little over a year’s time, this cofferdam will drain the Long Sault Rapids, and leave the riverbed open to the air, and to exploration.

VIII

|

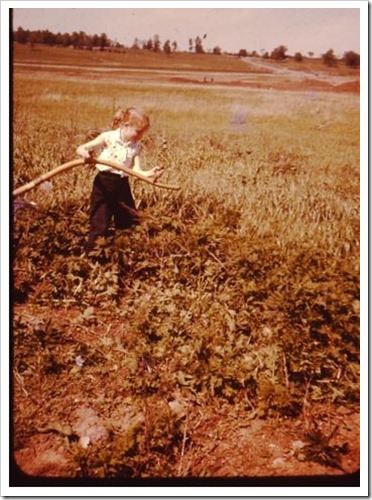

Moulinette, Ontario. What will be an island is still a field

|

My aunt Diane swings a scythe, along the future shoreline of Moulinette Island, named after a village to its east that will be inundated. Behind her, the rail bed of the Canadian National Railway, runs across the field. Its rails have been lifted and the line relocated to the north.

The road that crosses the rail bed, is a section of the route used to transport homes, from Milles Roches and Moulinette to the newly-created town of Long Sault. The rise of land, at the top of the photo, will become the northern shoreline of Lake St. Lawrence River, as the impoundment area created by inundation is termed.

Moulinette Island, is the 17th and furthest east of a string of islands, created by flooding; its official designation as “Island 17” still resonates locally. It is the eventual destination of a number of cottages, moved by skidding across the ice in the winter of 195-58, from nearby Sheek’s Island.

IX

|

October 1955. House moving at Iroquois, Ontario.

|

The Hartshorne house moving frame is an impressive, purpose-built machine, designed to winch houses up from their foundations and give them a slow, cushioned ride to their new locations.

Before inundation, 525 houses will be moved to the new communities of Ingleside and Long Sault, and to new residential neighbourhoods in Iroquois and Morrisburg. The latter two communities will carry on in name, but in a much-altered state, with their downtown business sections destroyed and rebuilt along the relocated sections of Highway #2.

The house-moving process left a great impression on the community. My grandfather frequently spoke of the fact that a house could be moved, with such gentle ease.

To those people who had come of age, in turn-of-the-century rural Ontario, and seen the advent of everything, from the television to the atomic bomb, this must have appeared as another example of humanity’s inevitable progress, toward a future defined by technological advancement.

X

Before the Seaway, the stretch of River, between Iroquois and Cornwall was, in equal measures, scenic and utilitarian.

The historical arc of the 20th century upset that balance. Economic growth, technological development, and global political currents,demanded more of the River than it could give, without being altered beyond recognition.

In time, a “new” River established its own character. Wind and water did much to erase the old River from obvious attention. But evidence of it remains, in the form of remnant sections of highway that slide into water, lengths of abandoned rail bed, and house foundations and stone fences, exposed when water levels are low.

Living along this new River means being confronted by remnants of a place and an age taken by floodwaters.

That lost River will never return—but it will be a long time before its past leaves it.

By Craig Irwin Stevenson