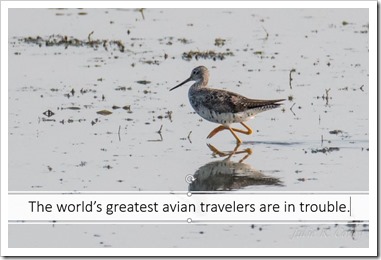

The world’s greatest avian travelers are in trouble. The Earth’s populations of sandpipers, plovers and their relatives have suffered significant declines over the last thirty to fifty years. A combination of factors including habitat loss, failing food supplies, disruptions by growing human populations, and climate change are all impacting these birds. The destruction of wetlands and other critical areas along migration routes and in wintering areas are major problems. While declines are greatest in the Asia-Pacific Region, numbers of many species are also decreasing in the Americas. For these and other reasons our area is hosting fewer of these wonderful birds every year.

Migration stopover habitat use has been a limiting factor for shorebirds in the North Country for at least the last century and three quarters. These birds were market hunted, whenever they were present, until receiving protection from the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918.

There are anecdotal references, in late nineteenth century ornithological journals to this practice in our region. This unregulated slaughter and associated disturbances greatly impacted shorebird populations, and their numbers plummeted. A general recovery occurred after protection but some larger species, such as American Golden Plover, have never recovered their former abundance. One species, the Eskimo Curlew, became extinct due to market hunting. These species remain legal game in Latin America, a fact that may be exasperating population declines.

Most species survived the market hunting massacres and recovered some of their former abundance by the 1950s. Even then, there were few concentration areas for these long-distance travelers in our region. El Dorado Nature Preserve, in southwestern Jefferson County, was the most productive of known local stopover sites. Protected by The Nature Conservancy in 1968, it hosted shorebird concentrations in the low thousands on some late summer days. Thus this site attracted birders from many parts of Upstate New York and adjacent Canada. Other local areas used by migrants were more hit and miss depending on water levels, rainfall patterns and human land use. Unlike Atlantic coastal areas, shorebird habitat here is unpredictable.

Unfortunately, by the late 1980s, fall migrant shorebird numbers began to decline substantially as sightings throughout the region decreased. Some of this was due to changes in the ecology of the St. Lawrence River and Lake Ontario. Pollution laws and arrival of the invasive zebra/quagga mussels greatly impacted nutrient and algae levels present. Cladophora green algae blooms decreased as eutrophication (increase of nutrients) of waters lessened. This in turn reduced the invertebrates that fed on rotting algae tossed ashore by wave action. Shorebirds who fed on the invertebrates thus had less available food. While generally the return of these water bodies to a more natural nutrient poor state is a good thing, it has had consequences for shorebirds.

The overall continental decline in shorebirds combined with other factors has currently made our region ever less hospitable to migrants. Development of shorelines, small isles and above water shoals has usurped important habitat. Increasing recreational use by ever larger numbers of people, particularly with uncontrolled dogs, greatly impacts these birds. These long distance flyers require quiet undisturbed areas where they can put on fuel for the next l eg of the journey. Frequent human disturbance alters the energy balance of these birds and impacts their condition for travel.

eg of the journey. Frequent human disturbance alters the energy balance of these birds and impacts their condition for travel.

Most shorebirds breed in the open Boreal Forest and on the Arctic Tundra. These great world travelers may span the globe, twice a year, in migration. Birds nesting on Baffin Island in the high Arctic may spend the Northern winter in Tierra del Fuego. They have evolved to chase seasonally abundant food resources across the globe. These are truly the birds of summer, pursuing endless fine feeding opportunities throughout their lives. Survival means moving from one smorgasbord to another on a precise schedule. They have evolved as species that are very good at exploiting their narrow ecological niches for survival. Unfortunately, when the planet’s dominate species changes game rules, such specialized species are usually the ones most at risk.

Shorebird migration through our region is very different depending on the season. Spring movements are highly rushed affairs driven by reproductive imperative. Lasting from late April into June, but intensely peaking in the last two weeks of May, breeding adults are in a great hurry. We usually see few of these birds as most overfly our region. Jumping off from the major staging areas near Delaware Bay, they reach their breeding grounds in a single flight. Only when adverse weather, such as heavy rain and strong northerly winds, ground flights for brief periods of time do we see large numbers.

While spring migration of shorebirds is a frantic affair, fall movements are very leisurely. It’s a short summer in the Arctic and as the last north arriving migrants are breeding, some species adults are already heading south. In the Thousand Islands region, the interval between these two occurrences is less than three weeks. The Arctic summer allows only one good shot at successful reproduction. If your nest or young are predated after they are well along in the cycle, there is no time to try again. The first southbound shorebirds are unsuccessful breeding adults that will have to wait till next summer.

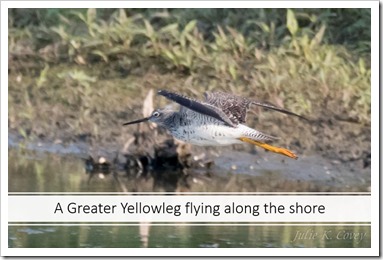

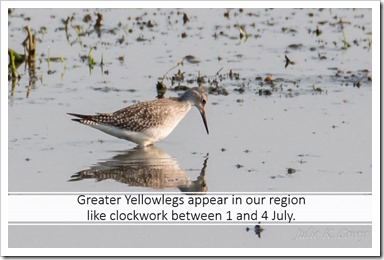

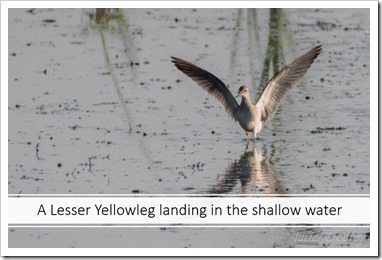

Early migrant species including Least Sandpiper and Lesser Yellowlegs appear in our region like clockwork between 1 and 4 July. Soon they are accompanied by unsuccessful adults of other species. From mid-July till mid-August, they are joined by adults that have bred successfully. Thereafter, most migrants are immatures, making their first journey south. It boggles the mind that these young make such immense migrations using only the navigation tools with which they were born. Immature migration peaks in late August and early September. By late September shorebird migration slowly tails off, except for Dunlin, whose movements peak in October and early November.

Information collected by me at El Dorado in the 1980s does show that our region is an important migration corridor for certain age groups of some species. Most fall migrant adult Semipalmated Sandpipers, presumably in fine physical condition, stage along the northeast Atlantic coast before flying over water to northern South America. Species counts, at the Manomet Bird Observatory in Massachusetts, of birds using this overwater route drop-off dramatically in late August. In contrast my data from El Dorado strongly indicates immatures use a more inland route to their wintering grounds. They are probably less physically prepared than adults for an arduous sea crossing.

So indeed, protection of suitable habitat locally for fall shorebird migrants has conservation importance. The efforts of the Thousand Islands Land Trust in preserving small islets and shoals will have definite benefit to smaller shorebird species such as the Semipalmated Sandpiper. Protected water bird nesting Islands, such as the Eagle Wings off Clayton and Little Galloo in Lake Ontario, definitely attract many fall migrants. Presumably there is increased safety in numbers should a wandering Peregrine Falcon pass by. If you blend in with the crowd it may eat someone else.

Even in late summer and fall, observing shorebirds locally is a challenge. El Dorado still hosts some numbers when water levels are reasonable. Often the small islands and shoals, of the River will host birds for variable periods of time. There can be high turnover amongst migrants, with some remaining only a few minutes, while others are present for days. Boating birders should carefully check small thinly vegetated islands and shoals, as well as muddy wetland edges,for migrants. Shore-bound observers can also check rain puddles in farm fields and other transitory wet areas. Seeing these interesting globetrotters is well worth the effort, although identifying smaller species can be a real challenge. That, however, is a topic for another time.