Editor’s Note: This is an excerpt from an early draft of Ian Coristine's coming non fiction book "One in a Thousand." It finds him flying up the St. Lawrence with two close friends, Maurice Patton and Maurice Vinet in three Challenger floatplanes over the Lost Villages section on a flight in 1992 which would lead to his discovery of the Thousand Islands. Our appreciation to Ian for sharing this glimpse of his future book with us.

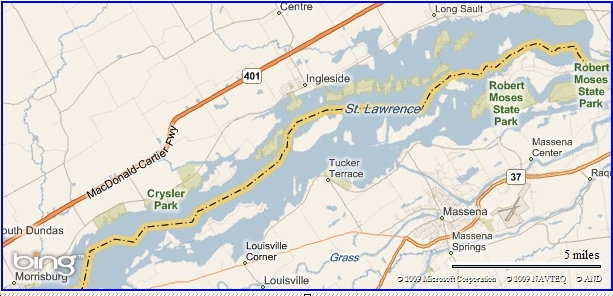

Civilization reemerges along with a bridge and a massive wall looming ahead. Throttles forward, we climb from the macro view to an expansive one as we hop over a massive complex that spans the River. Cornwall sits on one side with Massena, N.Y. on the far bank. Between are two dams and immense locks which raise and lower giant ships across the height of land. A spider’s web of high tension cables and tall towers radiate out in every direction.

Two neighbors are separated by the River and an international border, but joined by the bridge and the cooperation that now holds back Lake Ontario, over a hundred miles away.

For centuries this area was impassible due to rapids, preventing ships of any size from reaching the Great Lakes and the heart of the continent. The St. Lawrence Seaway changed all that while generating power from the largest reservoir of fresh water in the world. Long envisioned, this massive project was finally completed in 1958, literally changing the face of the earth, or at least this part of it.

We drop back down to water level, skirting forested islands that once were hilltops with the altimeter revealing this side to be 80 feet higher.

“What’s this?” I ask.

“I haven’t got a clue," answers Vinet.

“Looks like a channel.” Patton suggests.

|

To say we were baffled by this inexplicable channel, doesn't quite capture it. Why would anyone put so much effort into clearing such a perfect path through the weeds leading absolutely nowhere?

Photo by Ian Coristine © www.1000IslandsPhotoArt.com.

|

Perhaps ten feet below the surface we can clearly see a path about a wingspan wide perfectly cut through weeds growing on the bottom. As we follow it, geometrically perfect rectangles and squares appear here and there nearby.

“They’ve got to be man-made but what the heck are they?” I’m stumped.

The others are too. It never cuts deeper than the river’s bottom, is usually straight but occasionally arcs off one way or the other, going absolutely nowhere.

“Who or why would anyone want to go to so much trouble when it doesn’t go anywhere?”, asks Patton.

“No idea,” Vinet answers. “And it’s not as though there isn’t enough depth for most motorboats to move around here above the weeds.”

Determined to figure out what it is, we follow it intently for miles. Finally a small island lies in its path.

“This must be the destination because it’s going straight for it.” Patton sounds sure, but I’m not.

“There’s nothing here but brush and a few ducks.”

|

Known as the “Lost Villages”, ten communities were sacrificed to the Seaway, houses literally jacked up off their foundations and moved to higher ground before the inundation created Lake St. Lawrence.

|

The “channel” rises up to meet the island, sweeps across it and back into the water on the other side in a smooth gray ribbon.

“Was that a faint line painted down the middle?”, asks Patton as we pass.

It was. Faded but visible, the realization is instantaneous.

Painted 40 years before, it is the centerline of what once was a two lane highway which ran along the shore of a very different River. Foundations of forgotten houses, barns and buildings are the shapes we’ve been seeing.

It is a haunting realization, like discovering another Atlantis, if not quite so ancient. While boaters might catch a glimpse of this if they stopped long enough to let the water calm, it would be difficult to understand what they are seeing from the surface. I am reminded of our privileged view.

Known as the “Lost Villages”, ten communities were sacrificed to the Seaway, houses literally jacked up off their foundations and moved to higher ground before the inundation created Lake St. Lawrence. (http://www.lostvillages.ca/)

FOOTNOTE: Portions of the submerged roads can also be seen in satellite views on Google Earth (look between Cornwall and Ingleside, Ontario), though few (but you) would understand what they’re seeing.

By Ian Coristine, ian@thousandislandsbooks.com

Ian Coristine, the preeminent photographer of the Thousand Islands, produces Thousand Islands pictures professionally. His books and prints are available throughout the region, and as a community service Ian generously shares his images here in Thousand Islands Life. If you want to see more of his work, please see his website [http://www.1000islandsphotoart.com/] and we encourage you to subscribe to his Wallpapers, where he shares Thousand Islands scenes to use as screensavers. Each winter month you will receive a view of our River and our Islands – helping to build greater pride in our special section of the mighty St. Lawrence River.