Wolfe Island is special for many reasons, including its distinction as the largest island in the Thousand Islands. It is also unique in having two lighthouses that have survived and continue to function. The first Wolfe Island lighthouse was built on the eastern end of the island in 1861, on the point variously known today as Quebec Point or Quebec Head and earlier known also as Hemlock Point or East Point.

|

Photo courtesy of Michel Forand

|

An early postcard view of the Wolfe Island Lighthouse, built on the eastern end of the island in 1861. The Point has many names including: Quebec Point, Quebec Head, Hemlock Point, and East Point.

|

Tibbett’s Point lighthouse in Cape Vincent, New York, was the first Thousand Islands lighthouse built, at the outlet of Lake Ontario in 1827. Canada began a flurry of lighthouse construction in 1856, placing eight lights along the river between Burnt (Aubrey) Island in the Admiralty Group near Gananoque all the way downriver to Brockville.

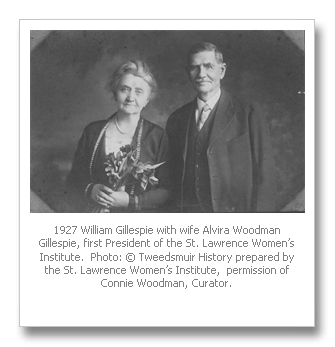

The Gillespie Dynasty

The Wolfe Island light was a wooden structure with four sloping sides, like all but one of the Canadian lighthouses in this area. The light was built at the behest of steamboat captains of the time, who recommended that the lighthouse then on Fiddler’s Elbow be moved to Hemlock Point. However, there is little evidence that the actual structure on Wolfe Island was physically moved to the site; the fact that three years passed between the removal of Fiddler’s Elbow Light and the construction of Wolfe Island Light further suggests that this was probably not the case, and a new light was constructed.

Like all of these wooden structures, the Wolfe Island lighthouse suffered from exposure to the elements, and was repaired and rebuilt several times, wholly or partially. The parsimonious British government of the day avoided the more costly construction associated with stone or bricks. These and similar river lighthouses were regarded as of secondary importance, and every attempt was made to keep associated expenses lower. The cost of constructing the Wolfe Island Light in 1861 was $470.50, resulting in a structure described as a “white, square, wood” lighthouse, 36 feet in height.

The first lightkeeper was Thomas Kilty, who acted in 1862 and 1863 only. He was probably the head lightkeeper, being paid $225 in annual salary, while his assistant, Robert Gillespie, was paid $123.62. In 1863, however, the proportions change, perhaps because Thomas Kilty did not stay for the whole season. From 1864 onward, Robert Gillespie acted alone as lightkeeper. He was to remain for over two decades, until 1885; he worked almost to the end of his life, and died on the 9th of June 1887.

Robert Gillespie was also to begin a dynasty of sorts. His son, William Gillespie, took over as lightkeeper on the 17th of March, 1885, remaining as the keeper for over 50 years. He had likely served as one of his father’s assistants as he grew up, and the government tended to appoint sons to take over, where suitable. The Gillespies were fairly typical in this way, in the position being handed down within the family. In the end, the Gillespie family were lightkeepers at the Wolfe Island Light for at least 77 years!

In 1912, during William Gillespie’s tenure as lightkeeper, the Wolfe Island lighthouse was rebuilt. This was a year of great change at the lighthouses on the Canadian side of the border. Fueling of the lighthouses had undergone many changes over the years. The lights, which burned whale oil for the first few years of their existence, were switched over to the more economical coal oil by 1860. In 1904, however, all of the lighthouses in the Thousand Islands were lighted with acetylene, which the government believed would “make the lighthouse system between Montreal and Kingston practically automatic.” The services of many keepers were now dispensed with, as one keeper could assume the duties for several lights.

Abruptly, in 1912, the lights reverted to coal oil. The Gananoque Reporter announced:

“Back to Oil. For reasons best known to themselves, the powers that be have decided to revert to coal oil as an illuminant for the lighthouses in this vicinity.”

It is not clear if the refitting of the Wolfe Island light was related to this change in fuel, or if the old structure had merely deteriorated to the point that a new one had to be built. A description of the light would now read: “white, square, wood, lantern roof red. 33 feet in height above the water.”

As the years progressed, the level of detail provided in the government records related to the lighthouses declined. Through examining various sources of information, a fairly complete list of the lightkeepers in the Thousand Islands can be compiled, but we can never be sure that it is quite complete. Government records of the time noted consistently that lightkeepers often had assistants who were paid out of the keeper’s own allocation, and who do not appear on official records.

There were at least two of these at the Wolfe Island light. Records show William Gillespie as the keeper of record in 1939, but later records note only that the light was “watched.” Descendents of Everett Woodman report that he took over as caretaker of Wolfe Island Lighthouse at about this time, until he retired in 1954. The lighthouse continued to be listed as a “watched” lighthouse for several more years, however, until 1960. Handwritten notes in a Coast Guard document confirm that this “keeper” was considered to be a caretaker, and may have been a Coast Guard employee.

We do know that further changes were made to the lighthouse in 1954 and 1971. The change in 1954 was the conversion of the lighting to electricity, which was when Everett Woodman retired. One result of this change would be that the light became more automatic, further reducing the need for a lightkeeper.

The lighthouse remains today, on a small plot of land owned by the Canadian Coast Guard, and continues to be an aid to navigation. It has lost its upper cornice and lantern, likely in the 1971 rebuilding, and is a ghost of its former self. Adding insult to injury, the owners of the land beside the lighthouse have built an accurate replica of a historic Chesapeake Bay lighthouse as a private residence, an amazing building that towers over the sad remnant of the actual Wolfe Island Light.

Brown’s Point Light

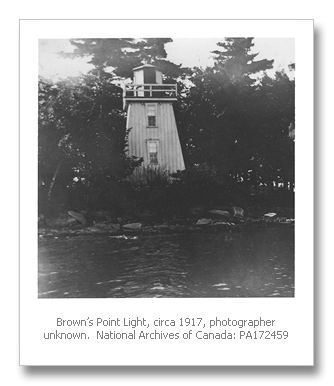

What’s in a name? The Wolfe Island Light got its name from precedence, being the first on the island. The second was the Brown’s Point also known as Knapp’s Point Light. Last built (in 1874) and most westerly of the Canadian lighthouses in the Thousand Islands, this light was known, interchangeably, as “Brown’s Point” and “Knapp’s Point” for the first 15 years of its existence. Rather abruptly after 1910, it became known almost exclusively as “Knapp’s Point,” the name by which it is still known today. Local reference to this as the “Brophy’s Point” lighthouse adds to the confusion. Brophy Point is actually located about 500 meters east of Knapp Point on Wolfe Island, but the land upon which the lighthouse sits was expropriated from the farm of William Brophy (who owned the entire Abraham Head area, including both points of land).

Brown’s Point Light was built “in the interests of navigation of the St. Lawrence,” and was similar to the other Canadian lighthouses here: “white, wood, square” and standing 20 feet in height. John Boyd was temporarily assigned as the first lightkeeper in 1874, but by the beginning of 1875 a permanent lightkeeper was named in Patrick McAvoy. In contrast to the Wolfe Island Light, Brown’s Point had no major structural modifications or alterations for over half a century. It was not until well into the 20th century that any significant changes were made to the lighthouse.

Also contrasting with the Wolfe Island Light, Brown’s Point Light had almost a dozen different lightkeepers during the years that it was a watched light, and at least one unacknowledged lightkeeper’s assistant.

When Patrick McAvoy died in July 1889, his widow Mrs. P. McAvoy (Catherine) became the second woman to act as lightkeeper in the Thousand Islands – or at least to be officially recognized as such. The “widow of J. Mervin” holds the title as the first, when she took charge of the Burnt (Aubrey) Island light for two weeks following her husband’s death. Catherine McAvoy acted as keeper of Brown’s Point Light for several months, however, until April 1890. She was followed by Hugh McLaren (1890-1896), Allan McLaren (1896-1905), Joseph J. Brophy (1905-1912), W.W. Card (1912-1917), W.J. Allison (1917-1919), Malcolm McDonald (1919-1922), J.J. Brophy (briefly in 1923), and J.S. Webster (1923-1930).

The St. Lawrence Women’s Institute’s Tweedsmuir History contains a photograph of a man named Johnny Wall, described as a “fisherman and lighthouse keeper on Brophy’s Point in the late 1880 to 1910” period. A descendent of the Brophy family tells us that Johnny Wall was a squatter, who appeared in the area in the 1890s, living on the government land around the lighthouse, and who made a living fishing. He was very crippled, but “in spite of this, he was able to walk with the aid of a cane with a very large brass tip,” and he “always wore a fedora and a big white beard.” There are no official records of his name, but it is likely that he provided occasional assistance with chores around the lighthouse during the years he lived in the area.

Wolfe Island Light was by far the last of the Canadian lights in the Thousand Islands to have a lightkeeper. By 1930, in contrast, the Brown’s Point lighthouse was no longer kept as a watched light. The government began to retire or stop replacing retiring lightkeepers several years earlier: after 1904, Windmill Point was no longer watched, and the trend continued at Grenadier Island (1923), and Cole Shoal (1927).

The first recorded alteration of Brown’s Point was in 1939, and almost certainly related to improving the automation of lighthouse operation. Another alteration in 1947 was most likely a conversion to electricity. When Thomas Ferris retired as lightkeeper of nearby Burnt Island light in 1947, the light was converted to electric power. A final alteration was reported in 1971.

Today, the lighthouse does not look substantially different than it has done from its earliest years. The light continues to act as an aid to navigation, operated by the Canadian Coast Guard. The Coast Guard has clad the tower in a low-maintenance siding, but it is otherwise little altered. The lightkeeper’s house that stands nearby is now privately owned, and used as a cottage.

More lights were added along the river during the 20th century, of course, as the lighting of the channel continued to be important. A current List of Lights details many more lights on and around Wolfe Island, but those stark steel towers bear little resemblance to the simple, elegant structures of the earlier years. The two 19th century lighthouses on Wolfe Island are remnants of an earlier age, and a valuable part of our cultural heritage.

By Mary Alice Snetsinger, ecoserv@kos.net

Mary Alice Snetsinger is a conservation biologist. She grew up in the United States and Canada, and worked for four years at St. Lawrence Islands

National Park. She became interested in the 19th century lighthouses of the Thousand Islands in 1997, and has sporadically researching them ever since. She notes that what is curious about both Wolfe Island lights is how difficult it is to find images. Several of the Thousand Islands lighthouses have been documented repeatedly over the years, in art, photographs and postcards. Not so for the lighthouses on Wolfe Island. She would welcome hearing from any reader with more images or stories of these or other Thousand Islands lighthouses.