“It is exasperating' said Capt. William FitzWilliam Owen as he sat in front of his surveyors' notes, deciphering the many triangles and drawings. "Much confusion arises in very important records and transactions, from the same name being attached to different places and from the same place being designated by different names."

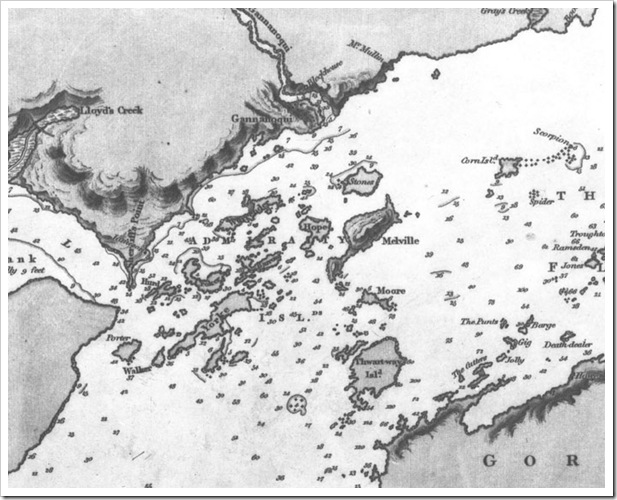

Photo: National Archives of Canada C2590

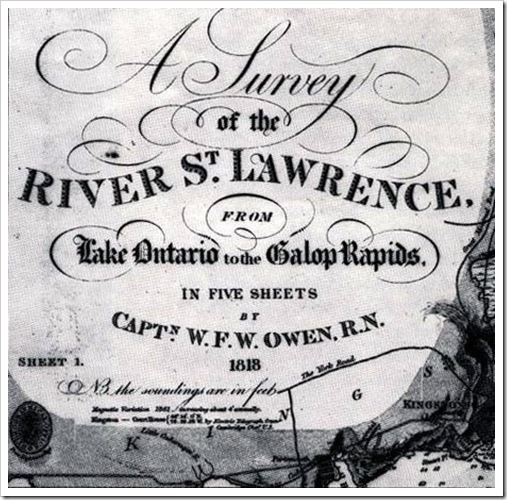

Captain William FitzWilliam Owen, British Admiralty hydrographer, wrote the plan to name the Thousand Islands for his survey in 1816.

There must be a better way to distinguish the islands of this section of the St. Lawrence River, he thought, a way to describe the islands and the passages that are safe for the King's Navy and the supply ships traveling west or east. Reviewing the charts, Owen wrote a memorandum to his officers and to the British Admiralty in London. A simple yet decisive plan was dated May 1815.

This was the beginning of the master plan to designate the hundreds of islands in the section of the upper St. Lawrence River, known as the Thousand Islands.

Owen began at Lake Ontario and moved east downriver to Brockville, choosing the names of prominent figures for major islands and dealing with the surrounding small islands as groups, naming them as well. He changed Wells Island to Wellesley Island, Grindstone Island to Gore Island, and Hickory Island to Francis Isles. The Nut Isles, described as Admiralty Isles from Gananoqui (sic) eastward, became Crokers Isles. Islands located between Gore and Wellington islands were called Barrows Isles. The islands east of Bathurst Island (Grenadier) and near Brockville became the Brock Isles.

Photo: National Archives of Canada V12 EC. Series 2, Sheet 2, 1868

Admiralty Islands, named after members of the British Admiralty Office working in Londonwen's charts, with depth soundings and names, were carefully recorded by his draftsman, Lieut. George Cranfield. Eventually they were sent to England and used by the engravers in 1828 for printing.

The final names, drawn on or beside the islands, followed the original Owen plan with some variations. If you study the charts you cannot help being intrigued by the systematic approach given to naming each section of the islands.

How did Captain Owen choose island names with such precision and so few inconsistencies? Some of the answers can be found in published biographies, but finding the members of the British Navy and Army who are commemorated so prominently on the Owen charts is more difficult. The task was made much easier by a 1909 publication at the Royal Canadian Military Institute. Written and edited by L. Homfray Irving, the Officers of the British Forces in Canada During the War of 1812 lists most of the forces involved in the war. Included in this, is the list of the Indian Department and the various chiefs who sided with the British. Irving not only names the officers and divisions, but in the footnotes we find many biographical references to those commemorated on Owen's charts.

Another good reference to the names of island is James White’s 1910 edition of Place Names in the Thousand Islands. Unfortunately, many references are incorrect. His work, however, gives excellent leads to finding the correct names.

Many Canadian city street names bear the same names as islands. This may not seem unusual, but history tells us that these streets were named on city maps long after 1815 and would have been for performing far greater deeds. A typical example is Sydenham, who was only a lowly employee of the Treasury Department at the time of the survey but was later appointed Governor General of Canada in 1839.

Owen's final charts divided the islands into thirteen groups. Some of these are easy to research. As soon as the Admiralty hydrographers began charting the high seas they prudently honoured the "home office" or those responsible for sending supplies and approving salaries. For this reason Admiralty officials were commemorated all over the world, especially during this era in British history when the navy and the Admiralty Office sent hydrographers and explorers in pursuit of discovery. In the Thousand Islands, the Admiralty Islands, near Gananoque, and the Treasury Chambers, near Rockport, followed this tradition.

Surveyors knew how essential the survey vessels and equipment were to the safety of the men. Naming the islands in the Lake Fleet, opposite the town of Gananoque, was an opportunity to acknowledge the vessels and their crews. Included in this list are the St. Lawrence (Ship of the Line), Prince Regent, Princess Charlotte, the Punts, and Gig.

The islands off present-day Alexandria Bay were called the Old Friends. They were the ships that Owen served on before coming to the Great Lakes in 1815. The Summerland Group served to recognize the hydrographers responsible to Owen for the surveys.

Many of the naval officers who were in the War of 1812 still served on the Great Lakes at the time of the survey, so the Navy Islands, west of Ivy Lea, offered an opportunity to honour the heroes and officers of the Royal Navy. The same was accomplished for army officers, with over 18 islands in the Brock Isles, opposite Brockville. In Chippewa Bay, the Indian allies were remembered. Seven natives who had fought and sided with the British during the war were honoured.

The group known as the Amateur Islands was probably named in jest, as it commemorates many who served in the Royal Engineers and not in the Royal Navy - "amateurs" in the navy's opinion. Captain Owen and the draftsman must have enjoyed the banter that was exchanged between the regiments serving in Kingston. Many of those listed in the Amateurs were members of the 70th Foot Regiment, that arrived in Kingston in 1814, near the end of the War of 1812. Several of these men were discharged at the same time as Lieutenant Cranfield. They could have traveled back to England on the same transport ship, the Vittoria. It is also conceivable that Cranfield worked on the drawings while on board ship and chose to honour his shipmates!

The largest group to be honoured were the officers who had fought in the Peninsular War with Arthur Wellesley, Duke of Wellington: over 54 soldiers' names were assigned to Canadian and American islands surrounding Wellesley Island. Owen, Cranfield and his surveyors would have had a hard time knowing who deserved mention on the charts.

The Peninsular War was fought between 1808-1814 and the Hundred Days War, which occurred after Napoleon escaped from the Isle of Elba and began his second siege, ended with the famous Battle of Waterloo in 1815. These battles were still fresh on the minds of the British public, but modern researchers may wonder how the team naming the islands knew who was important.

Perhaps the answer lies in the dusty volumes of The Gentleman's Magazine, first published in 1731 by an English printer. This monthly collection of essays and articles taken from other printed sources and published as a magazine was popular at the time of Captain Owen's survey. (Much like modern day Time, Newsweek of Canada’s Maclean’s Magazine.)

The Gentlemen's Magazine contained original poetry, fiction and a review of events in London and around the world. The editor often published war dispatches sent to London from battlefields around the world. Also included was a section of the "Gazette, &c. Promotions, Eccl. Preferments [Church of England appointments] and Obituary Notices." This is where we find a clue to the island names.

It is conceivable that Captain Owen brought several copies of the magazine with him from England, or he ordered them to be sent with other supplies from home. The magazines from 1814 to 1817, the year before he was sent to Canada and then while he was stationed in Kingston, include several references to promotions from "Whitehall, London:' The list shows the same names as the islands, and often in the same order as they appear on the charts. Other issues of the magazine list Foreign Office and Admiralty appointments. Some names that appeared in certain months were not used as island names, which leads us to assume that not all magazine issues made their way across the ocean.

Historians also credit the naming of the Thousand Islands to Henry Wolsey Bayfield, the naval officer who succeeded Captain Owen as chief surveyor when Owen was recalled to England in 1817. Bayfield was certainly involved, because his name appears on the first sheet of the survey: a large bay on the south side of Wolfe Island is called Bayfield Bay and shoals on the north side commemorate him as well. Bayfield worked in London at the Hydrographic Office in 1828, when the charts were engraved and published. He probably chose the final names to be included on the engraved charts and decided which names would be left off.

Over the decades many of the Owen island names have remained in use, such as Wellesley, Picton, and Murray in the U.S. and Hill, Mulcaster, and Stovin in Canada) while others never appeared on charts. Some of the Owen names were changed soon after an island was sold. This is especially true in the American sector, where local residents never saw the official Admiralty charts and soon gave family or descriptive names to their islands.

Photo: Map Index, National Archives of Canada V12 EC. Series 2, Sheet 1, 1868

Susan W. Smith SusanSmith@ThousandIslandsLife.com

Susan W. Smith © Historic Island Names first appeared in the First Summer People: Thousand Islands 1650 – 1910, Published by The Boston Mills Press, (Stoddart), 1993.

L. Homfray Irving, Officers of the British Forces in Canada During the War of 1812-15. Wellend, 1908.

David C. Chandler, Dictionary of Napoleonic Wars, New York. Macmillan Publishers Co. Inc. 1979.

C.P. Stacey. “The Ships of the British Squadron on Lake Ontario, 1812-14.” Canadian Historical Review XXXIV.