Written by

Chris Murray posted on January 13, 2011 22:27

For many of us the beauty and uniqueness of the Thousand Islands is without question. And yet we may know little of their origin. How were they formed? How long have they been here? The beauty that we see is a product of over a billion years of geologic activity. Eons of mountain building, erosion, and glacial activity have resulted in the islands as we see them today.

|

The Thousand Islands, part of the Frontenac Arch

Chris Murray © 2010

|

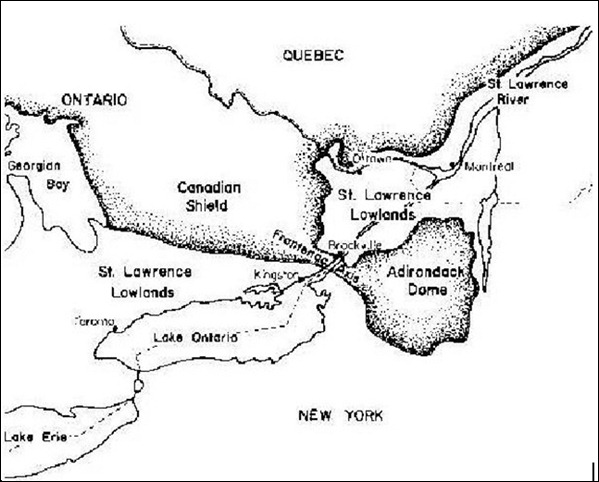

The Thousand Islands are a relatively recent geological feature carved from very ancient rock. The Islands as we know them were created at the end of the last Ice Age, approximately 10,000 years ago. However, the rock of which they are comprised is some of the oldest rock on earth, dating back to 1.1 billion years old. The pinkish hued Precambrian gneiss (pronounced “nice”) we see throughout the region is an extension of the vast Canadian Shield, a massive body of solid rock that forms the nucleus of the North American continent. The Thousand Islands portion of the Shield is known as the Frontenac Arch and connects the main body of the Canadian Shield to the west with the Adirondack Mountains to the east. It is interesting to note that the Adirondacks were also born of the same geologic forces that shaped the Thousand Islands.

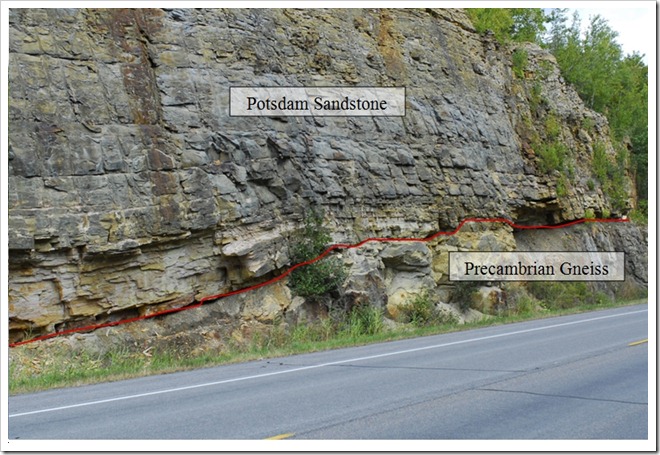

The Islands are actually the roots of an ancient mountain system that has been uplifted and eroded through the millennia. The dominant rock type that we associate with the islands is a combination of Precambrian granite gneiss and quartzite, both metamorphic rocks. Potsdam Sandstone is also prevalent throughout the area, particularly along the flanks of the Frontenac Arch.

|

Map of the Frontenac Arch, connecting the Canadian Shield with the Adirondack Mountains

|

The Potsdam Sandstone was deposited in a shallow sea and is much younger than the granite gneiss, roughly half its age at 500 million years old. While imperceptible to us, the uplift of the arch is responsible for the erosional stripping of the younger sedimentary rock such as the Potsdam and the exposure of the Precambrian gneiss. There is an interesting road cut a few miles east of Alexandria Bay along Route 12. It is an example of an unconformity, which is a gap in time between two rock types caused by erosion or non-deposition of sediment. Here the 500 million year old Potsdam Sandstone lies unconformably on top of the 1.1 billion year old granite gneiss, a gap in time of 600 million years11!

|

Unconformity (indicated by red line) between the Potsdam Sandstone and underlying Precambrian gneiss.

Chris Murray © 2010

|

While the rock is ancient the Islands themselves are a product of the end of the last Ice Age. The glacial ice sheet covered this region with ice miles thick, advancing and retreating on numerous occasions. The St. Lawrence River occupies an ancient geologic depression known as the St. Lawrence Lowlands. Prior to the ice leaving the valley the Great Lakes drained eastward through the Mohawk River Valley in New York. As the glaciers retreated northward into Canada the St. Lawrence Valley was initially filled with seawater. This can be evidenced in the marine fossils that have been discovered in the Thousand Island Region. However, as the land rebounded once the weight of the ice was removed the marine incursion diminished and the Great Lakes then began to drain via the St. Lawrence River. A thousand hilltops, the roots of ancient mountains, became the Thousand Islands in this flooded landscape.

|

Polished glacial furrow in Precambrian gneiss outside Keewaydin State Park.

Chris Murray © 2010

|

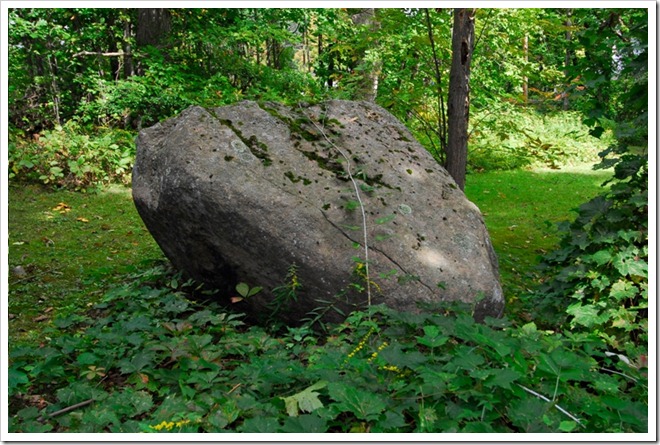

The islands are elongated parallel to the river, with blunt upstream ends and gentle downstream trailing slopes. Evidence of the glaciers can be seen throughout the region in the form of glacial furrows, glacial erratics, and potholes. A glacial pothole is a semi cylindrical hole gouged out of the bedrock by the scouring action of rocks and pebbles in the floodwaters of retreating glaciers. The best known (and largest) example of a pothole in the Islands is Half Moon Bay on Bostwick Island. Several smaller examples of potholes can be seen along the Eel Bay Trail portion of the Minna Anthony Nature Center on Wellesley Island. An example of a glacial furrow can be found in the road cut on Route 12 just outside of Keewaydin State Park. Here the bedrock of Precambrian gneiss has been scoured and polished by boulders at the bottom of the glaciers. Glacial erratics are boulders from elsewhere that were carried by the ice and then dumped as the glaciers melted. These can be found throughout the region.

|

Glacial erratic

Chris Murray © 2010

|

By Chris Murray

Chris Murray has been practicing landscape photography for fifteen years. During that time he has also worked as a geologist, earning his B.S. in geology from SUNY Plattsburgh and his Ph.D. from the University of South Carolina. He continues to work part time as a geological consultant, devoting the rest of his time to his photography.

Chris’ interest in photographing landscapes is derived mainly from his love of the natural world, the same love that led him to choose geology as a profession. [In June 2010, TI Life featured Chris in: Chris Murray's Photoraphy].

For Chris, the appeal of photography lies in the blending of the technical and the artistic. As a scientist, he is naturally drawn to the technical aspects of photography: decisions regarding filters, shutter speed, aperture, and so on. The skills he has learned as a scientist, the attention to detail and careful observation, have also helped him immensely as an artist.

Chris Murray resides in Syracuse, NY. You can find him online at Chris Murray Photography

1

Bradford B. Van Diver, Roadside Geology of New York, (Mountain Press Publishing Company), 295.