It was just before 5:30 am on June 11th when Captain Charles Dyon of the Windsolite heard the warning whistles amidst the early morning fog and set his sights upon that empty lifeboat, quietly hoping that her crew had already been rescued. Ordering the salvaged lifeboat to be taken aboard, he transported it to Port Colborne, Ontario and by 3:45 pm that day had placed it in the care of the port authority. He later recalled meeting another ship amidst the wreckage, but testified that it would not engage in any kind of communication, refusing to answer his hails.

Just over two months later, on September 2nd, the steel hull of a Teeside-built canaller would briefly feel the crisp fall air of Lake Erie once again amidst salvage attempts by the Maplecourt of Sarnia, Ontario. Unbeknown to Captain Tom Reid and his fearless divers, Jeffrey Skinner and Roy Perkins, their efforts were to be laid waste by a bout of stormy weather only hours later. That evening a typical fall storm shifted the four large pontoons that were fastened to her stern and the canaller turned upside-down, slipping back down the 72 feet to her watery grave on the floor of Lake Erie.

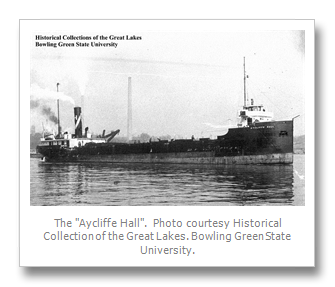

The year was 1936, the canaller was the Aycliffe Hall, the flagship of the newly reorganized Hall Corporation, and the final chapter in her short-lived career closed when all efforts at a salvage were called off the next morning.

Her story begins on Sunday the 15th of January, 1928, at South Bank on the River Tees, England. The Hall Corporation had contracted with Smith’s Dock Company of Middlesbrough to build ten ‘canallers’, of which the Aycliffe was the first of the second group, and fourth in total. Outfitted with two cargo holds and six hatches, she was powered by a triple-expansion three-cylinder steam engine. Her steel hull measured 253 feet long, 44.1 feet in beam and 18.5 feet in depth, giving her a gross tonnage of 1,900. Work on her was completed quickly; it took the yard only three months and two days to put her in the water on March 22nd, and two weeks later, on April 11th, she ran trials and was readied for her maiden voyage.

The Aycliffe held the distinction of being the first of her class, as well as the first in the Hall fleet to bear the ‘Cliffe Hall’ nomenclature which followed the fleet for decades to come. Named after the town of Aycliffe in County Durham, England, she was symbolic of the birthplace of Hall executive Albert Hutchinson, who was an integral part in securing the contracts with Smith’s Dock Company.

With a cargo consisting of 2,200 tons of fluorspar bound for Sault St. Marie, Ontario, Canada, and a unique ‘passenger’ in the form of the 65-foot tug Vigilant secured to her deck, she left the safety of the Tees on the 17th day of April, 1928, setting course for Sorel, Quebec, Canada, with a crew of nineteen Englishmen. On the 16th day of May she moored in Montreal, Quebec, was officially handed over to Frank Augsbury Sr. and joined the Hall Corporation fleet.

To the best of the writer’s knowledge, the first captain to take charge of the Aycliffe in the spring of 1928 was Captain William Herbert Ransom (1888-1931) of King City, Ontario. A Hall Captain since the early 1900s, he returned to the fleet to take her helm after a two-and-a-half-year hiatus following the drowning of his son from the John C. Howard in 1925.

The Aycliffe spent numerous uneventful trips on the St. Lawrence and Great Lakes hauling pulpwood, grain and coal throughout the following three years, although in the spring of 1931 a chain of events began that would encompass the following five years, and eventually culminate in her demise.

On Sunday, May 16th, Captain Ransom and his crew docked in Montreal, Quebec with a cargo of grain from Port Colborne, Ontario. The following Thursday, May 21st, Ransom along with Second Mate Charles Lawrence, Captain William Myles of the Penetang and Captain R. Scrutton of the Walter B. Reynolds, fueled with a good bout of drinking and poker, attempted to gain entry to the American Club on Mount Royal Place in the wee hours of the morning. They were refused, and a scuffle ensued between the sailors and a few locals, the result being Ransom enroute to hospital with severe head trauma. Captain Ransom passed away later that morning from a cerebral hemorrhage. The accused assailant, Jack ‘The Kid’ Thomas, a former professional boxer, was later acquitted in pretrial as the presiding judge deemed he was provoked.

The wheel of the Aycliffe passed briefly to Captain Walter M. Bowen (1899-1985) of Trenton, Ontario, who experienced only a few minor delays during his time.

In the fall of 1931, she was held up near Cardinal, Ontario with a load of grain downbound for Sorel. The delay was due to a ‘low level of water in the St. Lawrence River above Montreal’ which held up thirteen ships.

That same winter in 1931, the Aycliffe had an eventful lay-up when she spent the winter at the Montreal district of Cote St. Paul, frozen in ice upon the Lachine Canal rather than safe in port.

After Captain Bowen’s short stint aboard the Aycliffe, the wheel was passed to Captain James Ross Sinclair (1896-1960) of Toronto, Ontario. Sinclair had received his Master’s papers in 1922 and the Aycliffe had the distinction of being his first full- time charge. He would hold her wheel through to her very last days, five years later.

The fall of 1934 brought another small delay as the Aycliffe was one of many boats to seek shelter in Harbor Beach, Michigan, after a massive three-day storm hit Lake Huron. It was documented that ships making the passage that would normally take 48 hours were taking over 100 hours to do the same.

Another unusual trip occurred in the winter that same year with the Aycliffe loading corn at Prescott, Ontario, on December 2, and taking it downriver to Cardinal, Ontario, where she laid up with her storage cargo for the winter. At first glance this trip would not seem odd until it is noted that it is only six miles between the two ports.

The following year and a half were again uneventful as the Aycliffe worked the St.Lawrence River and the Great Lakes without any notable incidents.

That would all change in the late spring of 1936.

By all known accounts, Captain Sinclair left Sorel upbound light on June 8th, presumably headed for Collingwood, Ontario, to load grain. At 1:50 pm the following day, the Aycliffe passed through the Cardinal Canal. She was through Lock One at Port Weller at 3:10 pm on June 10th, and cleared the Welland Canal system at Port Colborne at 9:38 pm that evening. Even by today’s standards, six hours to clear the Welland Canal would be considered a very fast passage. Once clear of the canal, the Aycliffe met with heavy fog upon Lake Erie, Captain Sinclair ordered her speed reduced and retired to his quarters.

According to watchman Garnet Sample, daylight was breaking, but it was still very foggy and the Aycliffe was continuing on slowly. Sample had just called stewards Julian and Dicky Gaudet and returned to the stern when he sighted the Edward J. Berwind quickly approaching their port side. The canaller was no match for the 586-foot freighter, which was laden with 11,000 tons of iron ore. The ensuing collision tore a hole in the Aycliffe ‘big enough for a man to walk through,’ recalled Sample, and the impact threw him in the air. Sample gathered himself and quickly alerted the rest of the crew; upon returning to the deck he felt some relief at the sight of Captain Sinclair, clad only in his pajamas, barking out commands and getting everyone off and into the lifeboat.

‘The Captain was the last to leave the ship and as we pulled away, her engines blew up and her stern settled in the water leaving her in a vertical position with about a hundred feet sticking up in the air. She stayed that way for about half a minute.’ Sample would later tell a reporter. ‘Last I saw her, the spars were sticking above the water.’

The crew were picked up by the Edward J. Berwind, which stopped about a quarter of a mile past the wreckage of the Aycliffe. They would be all accounted for and taken to the Bethlehem dock at Lackawanna, New York, by 3:00 pm that afternoon.

‘An act of God’ was how Captain Sinclair would later explain it. ‘I’ve been sailing the lakes every season for 23 of my 39 years and I’ve never been mixed up in any way in any piece of sailor’s hard luck. Yes, sir, it was an act of God.’

At approximately 5:45 am on the morning of June 11 1936, the steamship Aycliffe Hall Official Number 147800, came to rest in 12 fathoms of water 18 miles southwest of Long Point, Ontario.

There is a very personal connection that my family shares with the Aycliffe, and I would like to finish by sharing it.

On June 12, 2004, I married into the Sinclair family when I took the hand of Captain James Ross Sinclair’s great-granddaughter, Amanda. When several years later her father shared the few stories of his grandfather that he could recall, it piqued an interest within Amanda and me to find out all we could of Captain Sinclair. Our journeys have taken us across Ontario, and along the way we have been fortunate enough to meet people that not only knew Captain Sinclair but were moved and inspired by his kindness, wisdom and hospitality. What we didn’t know when we started our research was that the Aycliffe Hall and its tragedies greatly affected our family more then we knew. Captain James Ross Sinclair, Captain William Herbert Ransom, watchman Garnet Sample and deckhand Sydney Gooding were all members of the Sinclair family, three brothers and a father.

This is dedicated to the men that survived that morning, and all the men that sailed with them upon the decks of the Aycliffe: Clarence Kenney, Charles Lawrence, William Jarvis, Glen Smith, Peter Cross, Marshal McIntosh, Vincent Hart, Julian and Dicky Gaudet, Alex McIntosh, John Meits, Melville Douglas, J. Balsey, James Tomkins, Thomas Hanlon, Garnet Sample and Sydney Gooding

May God bless you all with safe passage.

__________________________

A special thanks to the following people: Ron Beaupre, Bob Graham, and Jay Bascom (for passing on his wonderful article on the Aycliffe and to the National Marine Sanctuaries, Alpena, MI. http://thunderbay.noaa.gov/ for the use of the Aycliffe photograph.

My family and I owe you all an immense gratitude for their help, guidance, knowledge and stories that will be with us and generations to come.

__________________________

By Joel Godfrey

Philip Joel Godfrey was born in Sarnia, Ontario a city famous for shipping and rail. He claims he loved ships and trains when he was little and was pleased that this research experience for Thousand Islands Life’s articles, "has put me back in touch with that passion”. “I started this journey as a way of giving something back to our children so they know where they came from”. Joel works in the Canadian Casino industry.

Joel’s wife, Amanda Godfrey (Sinclair) comes from Toronto, Ontario. She is Captain Sinclair’s great-granddaughter. (Her grandfather was Ross, her father is Ross and her half-brother is Ross.) She is a photographer and is personally responsible for starting the search for her family. That search led to Joel’s first article published in our September 2010 article, Captain James Ross Sinclair… a family discovery.