We initiated this "Pisces Redux" series of fishing articles with a less favored species (or at least less popular among native river anglers), carp, in order to avoid the obvious--which is what most of us fish for and have always prized: bass.

Bass is not the "king" of local fish due to size, like sturgeon or muskie. It is not so plentiful as other species, nor is it especially a gourmet prize. So what is so special about our bass? It is gamey. It is a sportsman's fish, the traditional lure to the true angler.

'Twas always so around here, or so it seems, since the days of our most famous fisherman (and original island cottage dweller), Seth Green. Seth might frown to see most of our bass fishing today, since he was of the old school of fly fishing--true "angling." But since the early 1990s, fly fishing for bass, particularly smallmouth bass, has again become popular again.

Bass is a fighting fish. Although not large, it can be a challenge for light rod and reel. John Alden Knight said, in his fine book, Black Bass, “For the life of me, I can’t understand how anybody can doubt that bass is endowed with an inherent pugnacity is second to none in fresh water.” Dr. James A. Henshall observed, in his Book of the Black Bass, “Ounce for ounce and pound for pound, the gamest fish that swims.”

There is a certain mystique to bass fishing. Charles F. Waterman, in his Fishing in America, observes that “Black bass are considered among the more intelligent of fishes and part of their appeal is the vast array of equipment" that ingenious humans invent to lure the wiley bass, such as the famous Skinner spoon long produced in Clayton--the first arificial lure popularly used (although more for muskies than bass).

The term, "black bass," is generic, including both smallmouth and largemouth bass, but excluding some other species known as "bass," such as rock bass. The black bass is a member of the perch family. Distinctions between smallmouth and largemouth bass may seem slight, but anglers appreciate differences in behavior and habitat. Smallmouth bass tend to jump more and fight aggressively on the surface when hooked, in order to throw the hook. Generally, the smallmouth bass is more prized--at least here--and is more characteristic of Thousand Islands. Smallmouth bass prefer cool, deeper, swift water and rocky shorelines, where it cruises in the shadows. Smallmouth are most often found in runs and pools, and a frequent succession of riffles, runs, and pools is an indicator of a good smallmouth site. On the river, bass congregate where narrow channels with fairly fast currents open into broader reaches of slower water--just as they do at the inlet from a faster stream to a lake, or where there is an under-water "waterfall," where faster moving surface water drops into a deeper pool. The "hot spots" of course provide more abundant food supply, concentrated in a small area. Bass will especially favor such a a hot spot if it provides fairly deep water near to broken, rocky contours that offer cover, where the flow is steady and cool.

Occasionally some exceptional source of food will cause bass to congregate in less typical places, and some scattered bass will always wander all over the river, but if one is unaware of prevailing bass preferences, one may spend many hours and days futilly fishing in relatively barren waters.

Bass may move out to deeper, cooler water later in a warm season, or if the water level drops. But barring radical change in conditions, bass concentrations will tend to remain in the same places. Obviously, this is why experienced local fishing guides serve bass fishermen well.

Smallmouth bass are not timid, like shy trout and salmon, which tend to panic with freight when disturbed. Bass will not flee from an approaching boat, but will merely move a prudent distance and retain that safe margin. Largemouth bass, however, when disturbed tend to hide under cover, "playing possum" until dislodged by poking with an oar or stick.

Bass are not deaf, however, as relative boldness may suggest. To the contrary, they seem able to distinguish between friendly and threatening noises. The bump of an oar against a metal hull may ruin fishing for some time, over a considerable distance. Also, loud conversation aboard, or raucous laughter, may cause your bass to move away. Some people think that fish can't hear noise if it originates above the surface of the water. 'Taint so. Actually, fish don't "hear" noise, but feel the vibrations in the water caused by the noise.

Bass, like other fish, can "smell," or at least taste certain substances in the water. This is how they distinguish edible from inedible material in the water--and why certain smelly lures work. Evidence is provided by the notorious ability to sharks to detect even small quantities of blood in water, over large distances.

Fish distinguish acutely between colors, which is why some lures will be successful only in a certain color.

Although we can't know, it seems that fish are insensitive to pain, as indicated by willingness to continue fighting when injured, rather than fleeing.

Fish become accustomed to familiar motions, like waving of tree branches over head, which is why slow movement of the rod tip, which surely is visible to the fish, is not alarming if not abrupt. But erratic paddling, changing from side to side, is assured to alarm any nearby fish--and is not the way to paddle a canoe at any rate.

Largemouth and smallmouth bass were not clearly distinguished initially, since they appear so similar. Anglers observed the distinction more in terms of habitat and behavior--the largemouth bass more generally appearing in shallower, slower, weedier waters. Furthermore, largemouth bass--called "Oswego bass" in the nineteenth century--were less feisty in breaking water when hooked. But this is a matter of personal experience. John Alden Carpenter, to whom we are indebted for many of these observations about fish behavior, argues: "Many fishermen 'low-rate' the Largemouth, claiming that he is far inferior to the smallmouth. Well, every man to his taste, but I always suspect a man's knowledge of bass and bass fishing when he makes that statement. The honest, enthusiastic, unrestrained, whole-hearted way that a Largemouth wallops a surface lure has endeared him forever to my heart" [Black Bass].

Despite similarity of appearance, in the nineteenth century experienced anglers began to note consistent differences. Dr. James A. Henshall, in his Book of the Black Bass, observed that "the large-mouthed Bass is thicker, especially through the shoulders, deeper in the body, with more pendulous abdomen, and seems a heavier fish for its length than the other species, conveying the impression that it is the stronger and more powerful fish, as, indeed, it is; while the small-mouthed Bass, owing to its trim, slender and more graceful shape, truly convinces one that it is the more active and agile."

Veteran Clayton guide Allen Benas agrees: "If there is any one species of fish that the St. Lawrence River and Thousand Islands are noted for, it would be the smallmouth bass. For over a century, anglers from across the U.S. and Canada have converged on the area to enjoy their second favorite sport. The Bass Anglers Sportsman Society discovered the area in 1977 and held their 1980 Bassmaster Classic here. A tournament held here in 1985 set an all time BASS record for the total weight of bass caught during a tournament with a five fish daily limit. The record stood for nearly a decade.

"All fish species tend to have year to year cycles of high and low populations. My thirty years of guiding have seen years when pike were abundant and bass scarce, only to reverse in a few seasons. I can recall several years, not too long ago, when it was difficult to catch a legal bass. That was good, because when you don't catch little fish, don't expect to catch big fish down the road.

"The past few years have been the years of the bass,and for bass anglers, the past two years have had an added bonus, bass that have easily surpassed the traditional "average" size of one and a half pounds. Two to three pounders have become the norm with fish in the three to four pound class very common.

"Worth noting is the great increase in large bass on the St. Lawrence with sizes approaching those caught in Lake Ontario, which have always been larger than in the river."

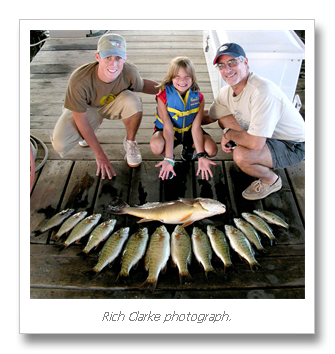

Capt. Rich Clarke agrees: "Yes, the bass are getting huge. It is common to catch small mouth bass from 3.5 lbs. to 5 lbs.+. The main reason is an abundance of feed. The river is rich with bait fish such as perch and gobies. In June they can be found in and around shallow rock shoals. They are a riot to cast for in the early season. Later in July and August the small mouths go deeper and start to school up in huge schools. In the mornings and evenings they feed on the shoals and then return to deep water. The bass fishing remains great right into October, at this time they begin go super deep, often go to a hundred feet of water. They can still be caught in great numbers in deep water.

Every day is a challenge for bass because they can be anywhere. This is when a professional guide comes in. The guides are aware of the patterns that the bass are in at any given time and can really help you find the fish."

Allen Benas adds:"Many factors determine the size of mature bass. Factors include the quality of water, temperature of the water and numbers and health of spawning fish during the hatch year. Factors between then and maturity, around five to six years, include the level of predation and food supply. We are told that it takes a St. Lawrence River bass about six years to reach the legal minimum keeping size of twelve inches. With two to three pound fish being around eight to ten years old, conditions must have been just about perfect back in 1998-2000.

"Over the years, the river has changed with many of the changes having affecting on the bass fishery. On the negative side are zebra mussels that moved spawning bass from traditional areas to deeper depths in order to avoid the mussels that give off ammonia as a by product, killing fish eggs. Round Gobys, another invasive specie, eat the spawn of every specie of fish. On the positive side zebra mussels seem to have diminished in number and gobies are a regular source of food for growing bass, pike and perch. Anglers are also more prone to catch and release fishing, keeping prize bass only long enough to take a picture or two and keeping only enough "eating size" bass for a fish fry. Bass over fifteen inches are not considered good table fare. How long this will last is anybody's guess. The bigger question will be how many small bass anglers will be catching over the next few seasons to continue the current trend. While it's great to enjoy the present, we must keep an eye on the future."

Steven D. Price, in America’s Best Bass Fishing: The Fifty Best Places to Catch Bass, notes that “What is truly amazing about fishing in the St. Lawrence is that while it is huge river, extending nearly a thousand miles from its headwaters at Lake Ontario through Montréal and finally to the Gulf of St. Lawrence and to the Atlantic, the best fishing by far is centered within a fifteen-mile area around Clayton and Alexandria Bay that can be easily enjoyed by anglers of all experience levels.”

Jack Mitchell adds: "The Thousand Islands, being very rocky are places that small mouth bass species love to stay and live. … It is the fabulous bass fishing of the Thousand Islands region that attracts the attention of anglers competing in Thousand Islands for bass fishing."

"The water is clearer, and baitfishes are abundant. The bass always make access to the bait and make feeding better. Because the zebra mussels have cleared up the water, vegetation is more widespread, which means the bass have better overall habitat. Both the largemouths and smallmouths are thriving."

"While the bass may be both larger and more abundant, they are still found in the same areas discovered by touring pros. In St. Lawrence, those areas include Lake of the Isles, Goose Bay, Chippewa Bay, and the rocky coves and points around the Admiralty Islands. In Lake Ontario, the key spots are Fox and Grenadier Islands, and Chaumont Bay."

“[Chippewa Bay was site of] Bo Dowden’s 1980 Bass Masters' World Classic world championship, in which he boated more than fifty-four pounds of bass in three days. Dowden’s technique that week was basically working a jig down around the rocks—the very same technique that works so well today.”

Jim McLaughlin observes, "Clearly, vegetation is a key for bass. Pencil reeds, hydrilla, lily pads and cattails were mentioned as favourite bass habitat that can be found around the Thousand Islands. Docks are objects that provide great cover too."

"Characteristics of Thousand Islands of Ontario make the place greatly known for bass fishing. The geographical aspect, location and richness of its great lakes and rivers make bass fishing a sport or hobby very inviting."