Most of us have spent a lifetime—or a lifetime of summers—on the river without ever even seeing, let alone catching, a Muskellunge. In the past, women as well as men were noted muskie anglers:

More recently some have landed them in astonishing numbers. Famed muskie fisherman, Dr. Howeth Pabst was winning awards with his 1,288th catch! The Syracuse dentist and his wife, Dorothy Urschel Pabst, of Wellesley Island—she also a dedicated muskie fisherperson--would come up to Clayton and troll the river for days on end, often in daunting November cold, rain, and snow. This is what it takes to be world-class muskie anglers. This also, of course, is why most of us have never caught a muskie.

Our resident authority, Dr. John M. Farrell of the Thousand Islands Biological Station, Clayton, tells us that “the St. Lawrence River provides one of the few, large, self-sustaining populations of muskellunge in North America. This population is thought to be genetically unique.

Farrell states, “the unique Great Lakes muskellunge genetic strain consistently produces some of the largest muskies caught anywhere.” John observes, “As the largest predator in the ecosystem, there are naturally fewer muskellunge in the river than other fish, much like there are fewer wolves than rabbits in the forest.”

Records were not kept methodically back in the nineteenth century, but newspaper accounts suggest that muskie population varied periodically. In the season of 1883, for instance, despite three years’ enforcement of new fish and game laws that prohibited netting, was said to be “remarkable for almost total absence of muskalonge [sic].” Muskies reported in the press were mostly in the thirty-pound class. Miss Annie Lee, eleven years old, in that year, 1883, landed a four-foot six-inch muscalonge [sic] weighing thirty-six pounds. Muskies were more plentiful the following season, when a party returned with four white flags raised, the signal of fortunate muskie hunters—and the four muskies had been caught in merely two hours.

“The largest muscalonge ever taken from the St. Lawrence” in 1885, four-four eight-inches long, weighed forty pounds and was landed after a half-hour fight. A muskie brought into the Hubbard House, Clayton in 1886 was nearly five-feet long, thirteen inches across the tail, weighting nearly thirty-eight and a half pounds.

The season’s largest muskie brought in by August 10, 1891 weighed thirty-seven and a half pounds. A forty-two-pound muskie was news in 1893, when fish running thirty to forty pounds came in daily. In the next two years trophy muskies weighted thirty-five and thirty-seven pounds. But in 1895 C. H. Chester of Chicago returned to the Hubbard House with a sixty-seven-pound pickerel [sic]! Are we to believe this, even if it was a muskie?

In 1896 an American Canoe Association camper landed a thirty-six pound muskie. In 1901 thirty-one and thirty-five-pound muskies came from Canadian waters. Two fishermen landed three muskies in one afternoon in 1903. The largest was four-foot-seven-inches long, weighing thirty-six pounds, the other eighteen and seventeen pounds. The previous day they had pulled in a twenty-pound muskie. The total for two day’s fishing around Grenell island was eighty-two pounds.

In 1910 a thirty-eight-and-a-half pound fish was landed near Grenadier Island. But in the same year Jerome Summers of New York City brought in a forty-eight-pound monster off Butternut Island, after a two-hour fight with a light rod and line intended for bass. He had to tow the fish to shallow waters to land it.

Muskie fishing was better in 1911 than it had been for many years. Thirty-five-pound catches were then “not uncommon.” The next year Edward Page of New Orleans brought four-foot-five-inch muskie back to Clayton’s Walton House. Weighing forty-three pounds, the fish, caught at Boxin Bay, off Wolfe Island, was “largest for several weeks."

While muskies generally seemed ample in supply, no record fishes were reported during these decades of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The heyday of Muskie fishing on the river apparently came in the second quarter of the twentieth century.

Muskie population declined after the 1950s, when Dr. Pabst and others were landing trophies in record numbers. Muskies come large: one caught here set a new world record at 31.397kg (69 pounds, 14 ounces). Among fishermen there seems always to be argument about records—debates becoming impassioned and acrimonious, as demonstrated by exchanges, documented on many web sites, and indeed in a whole book, regarding the record muskie, weighing sixty-nine pounds, fifteen ounces, caught on the river by Art Lawton in 1957. In short, “fish stories” have never been known for reliability.

This controversy about the world's record muskie is fascinating--and comical. We don’t get into the details here but some readers may like to follow the story, checking the many web sites if not reading the whole book.

Many champion muskie anglers are remembered at the Muskie Hall of Fame of the Thousand Islands Museum, Clayton, initiated in 1970 by Ed Bannister. Gale Radtke landed a fifty-two-pound fish a few years ago, the largest recorded muskie caught in the Thousand Islands in nearly a half-century. The lure was a Pike Minnow manufactured by Radtke. There is a claim that a seventy-pound muskie, caught recently in northern Ontario, mounted and displayed at the Gananoque Inn, is the world’s record. Or this may be the muskie caught recently in Gananoque waters, said to weigh sixty-nine pounds, fourteen ounces (31.397kg). But officially (so far as there is any reliability in these matters), after disqualifying contesting claims, the current world record muskie weighed merely sixty-seven pounds, eight ounces. The fish was landed by Cal Johnson in 1949, in Hayward, Wisconsin—but it, too, is subject to suspicion.

Ours are among the few waters that favor growth of record-class muskies, which require particular habitat, while poor water conditions retard proliferation. Presently authorities propose increasing minimum size limit from 112 cm (forty-four inches) to 137 cm (fifty-four inches) to promote a record class fishery.

Muskie fishing is for the hale and hearty. A tradition in Capt. Rich Clarke’s family brings fishermen out on Thanksgiving morning. Here they are, in twenty-six-degree temperature, with twenty-five-mile sustained winds on the water (gusts to thirty-five), plus snow, sleet and huge waves:

Anglers and guides began to express concern about muskie fishing in the 1940s. Muskie population has declined subsequently, especially since the 1950s when large numbers were still being taken. The downward trend was reversed two decades later. The New York State Department of Environmental Conservation and the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources recognized in the late 1970s that critical information for making management decisions regarding muskellunge was needed.

In August 1974 representatives of the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation met at Cape Vince, Clayton, and Ogdensburg with professional fishing guides and anglers, asking them to release voluntarily muskellunge under thirty-six inches long, although the legal minimum size was twenty-eight inches. Consciousness of the problem was raised and about 1980 a voluntary practice of catch-and-release began. The first comprehensive plan for the management of muskellunge in the St. Lawrence appeared in 1980. Standardizing of Canadian and US governmental regulations was recognized as a goal in 1980, finally attained in 1991.

In 1987 the environmental organization Save the River introduced a more formal catch-and-release campaign on the river, facilitated by support of the State University of New York’s College of Environmental Science and Forestry (SUNY-ESF) Thousand Islands Biological Station (TIBS), and local fishing guides. This program over the past twenty years stemmed the adverse tide of muskie decline. More than five hundred muskies have been caught and released since 1987.

The catch-and-release program provides anglers who certify that they have caught and released a legal-sized muskie a limited edition muskie print signed by local artist Michael Ringer. The decision to return the muskie to the water, relinquishing a giant trophy, may be made easier knowing that taxidermists can create a replica of the fish from photographs and measurements.

A local guide, Captain Clay, observed that during eighteen years of the catch-and-release program, muskie fishing “is three-hundred per cent better than it was in the seventies and eighties. Landing a forty- fifty-pound muskie happens almost weekly…and between ten and fifteen fish in the fifty-four- to fifty-five-inch range are being caught each season.”

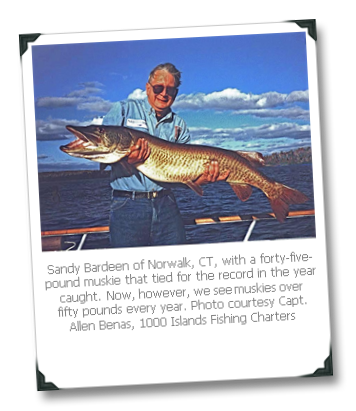

Capt. Allen Benas of Clayton, in an excellent article about muskie fishing, observed that initially it was expected that the catch-and-release program would take time to show significant results. A thirty-pound muskie is about eleven years old. During the 1980s and 1990s, thirty- to thirty-five-pound fish were trophies. They are "small" today, twenty-six years after initiating the catch-and-release program. Now forty- to fifty-pound muskies are very common, while a fifty-plus-pound fish is caught every season.

Those forty- to fifty-pound muskies are usually twenty to twenty-five years old, and even smaller “keepers” are probably females who may lay several-hundred-thousand eggs during every spawning season. This is why releasing a catch is so important to sustaining the muskie population.

John Farrell observes, “Release of adult muskellunge not only provides an opportunity for someone else to catch that fish, but also promotes recruitment of young to the population. Studies have shown an increase of over three inches in the average size of muskies and some impressive reproductive success in recent years.”

Hold the euphoria. Dr. John Farrell says, “We want to send out an alarm that VHS is killing muskellunge.” John is station director of the Thousand Islands Biological Field Station, Governor’s Island, Clayton. VHS (Viral hemorrhagic septicemia) is a disease attacking more than thirty fish species.

“There has definitely been a change,” John observes. The numbers of muskies caught and tagged by the Field Station staff dropped from forty in 2003, to twelve in 2006, and merely four last season.

Before 2005, staff generally discovered one dead muskellunge a year. In 2005, however, they found twenty-five carcasses. In 2006, however, they found merely about a dozen. Last summer, they came across half that number, about six dead muskies. Perhaps the disease has peaked, considering numbers of dead muskies discovered.

Although this might be cause for optimism, the biological station reports fewer young muskellunge this year, while fishermen are landing fewer than in the past. No doubt it will take time to replace breeding muskies lost to VHS—all the more reason to stress importance of catch-and-release.

The Clayton Field Station, which has been studying muskies for twenty-five years, witnessed a population spurt some seven years ago when the catch-and-release program effects became apparent.

Muskies measuring fifty inches and up are becoming more common, while even the rare sixty inches has been encountered. Several guides tell of landing muskies that weighed fifty-five pounds or more.

By Paul Malo