The first thing 10-year-old Grant Peacock did that summer morning early last century was disobey his mother's rule about not climbing up on the seawall. He ran down the front stairs of the mansion on Belle Isle, out the door past columns holding up a two-story porch and across a grass lawn cut like a putting green. He ran to the island's edge and boosted himself up onto a low stone wall that surrounded it. He looked down at the rapid waters of the St. Lawrence River streaming past just feet below him. He raised a hand to shield his eyes from the glare of the morning sun, and peered intently a half mile downstream at a barn-like building nearly 130 feet long and some 70 feet tall sitting in the water off the far shore. It was his family's brand new yacht house. He could hear grunts and shouts of muscular men as they worked mechanisms and ropes inside. His heart pounded. The spectacle was about to begin.

Suddenly, an explosion of steam belched forth from an open-sided cupola at the very apex of the structure. Windows in the dormers lining the roof rattled. Three successive tiers of doors that made up the entire river-facing facade began to creek open. Light crept in upon the dark interior as the building came alive. The moment was at hand: the grand yacht Irene, in all her buffed, polished and scrubbed Herreshoff glory, was about to be revealed.

One hundred feet long, she emerged stern first into the morning light. Despite being powered by steam, she still carried 40-foot masts, which were strung with colorful flags. Her teakwood decks were immaculate and her polished fittings gleamed in the sun. Her captain brought her about, heading for the island where young Grant stood. As he would recall: 'She sparkled like a piece of jewelry floating on the river.'

Young Grant climbed down from the seawall, hoping he had not been seen. His mouth watered as he thought of the day ahead: the long cruise aboard the yacht, the big ceremony over anchoring in safe waters, the deploying of skiffs for fishing or to row to an island for the shore picnic. There would be freshly-caught fish grilled by the crew over open hickory fires, and bacon, French toast, hot maple syrup. He ran back across the lawn and darted to the side so he could slip onto the breakfast porch, where he knew his family was already gathering. As his mother turned to tend to one of the other four children, he slipped to his chair, ducking beneath the big puff-sleeved shoulder of her long white day dress.

Some seventy summers later, sitting in his home in Bronxville, New York on a spring day in 1974, octogenarian Grant Allen Peacock fell silent. The memories had overpowered him.

It was precisely to hear such stories that I had sought out Grant Peacock. He was one of five children of Scottish immigrant Alexander R. Peacock and his wife, Irene. Peacock senior had grown rich selling steel for fellow Scot Andrew Carnegie, and before long he was sending his family and servants and their iron-bound trunks up the 450 miles of mud roads from Pittsburgh to the popular summer resort of the Thousand Islands. Young Grant was about ten. By the time we met, he was reaching 80 and retiring from a 56-year career in a jewelry business he built in New York City. I was a student at Columbia University, and I had selected the Peacock's steam-belching building of yore as my subject for a writing class. I had grown up in the Thousand Islands not far upstream from the fantastic structure, one of the last to survive from the period.

This watery garage for some rich man's boat had always fascinated me. It was at the heart of the near-mythic local lore of that first decade of the last century which had filled our child imaginations. There was the larger-than-life George Boldt, the Astor-financed operator of the new Waldorf-Astoria Hotel in New York; he had built a fantasy castle modelled on one on the Rhine and had even conjured up an island from the river waters so that he could watch the castle being built - it was Belle Isle, later bought by Peacock's father. There were tales of wealthy young men who, should they tire of polo or golf in the morning, could turn by afternoon to the more dangerous sport of racing mahogany speed boats up and down the St. Lawrence like latter-day jousters. There were stories of opulent yachts set with silver tea services, of the concoction of 'Thousand Islands dressing' by the Waldorf's maitre d'hotel Oscar Tschirky, of islands lit round at night with amber-colored lanterns. For an annual yacht club dance, one of the Peacock boats was filled with chrysanthemums and dummy people and set inside the ballroom to simulate a joy ride.

All was eased by the presence of dozens of servants. Grant Peacock himself remembered that his own family's constant stream of guests and business associates from New York and Pittsburgh were tended by some 20 staff in the house alone: three or four in the kitchen, two or three butlers, chamber maids, laundresses, his mother's own maid. They were Scots, English, Swedes, Japanese, German, French, Italian. The yacht crew numbered another eight or nine living in the yacht house. Farm hands and managers brought the help number close to 60.

I needed Grant Peacock to fill in the blanks for me, to talk first-hand about this extraordinary building, and the requirements of life and boating at the time that had brought it into being. The single most important reason for the design, Peacock related, was the fact that steam power was still fairly new and people were not comfortable seeing their yachts without the customary lofty masts previously needed to carry sails. So the yachts, although steam powered and not needing sails, still had their masts. 'They had no function,' Peacock said. 'It was a hangover from the days before steam, when sails were used. The spars were part of the beauty. You'd miss them if they weren't there.'

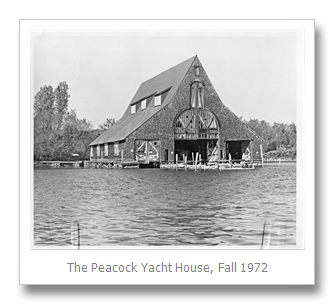

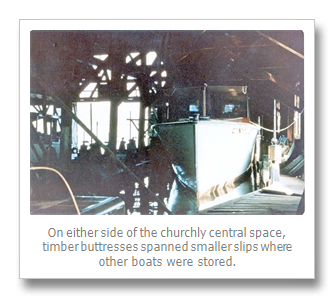

The challenge was clear. If the yacht was to have an indoor home to protect it from the weather and the winter, a structure had to be designed that could accommodate both the tall masts and a power system dependent on steam that would be belching from a smoke stack much lower than the masts. The result was a unique design of which three features particularly stand out. First, a lofty cathedral-like opening and interior had to be created to accommodate the masts. Hence the three tiers of doors on the river-facing facade; the number of doors to be opened would depend on the height of the masts of the ship entering. Once inside, an extraordinary maze of frames, cross beams and laminated wood arches formed a complex support system to achieve the necessary height. The curves of the wood arches were made up of hundreds of tiny wedge-shaped wood laminations. There were seven sets of these wooden arches over the center slip to achieve a cathedral-like height. 'The center slip accommodated the yacht each night, her tall spars passing through the cut-out area,' Peacock recalled. 'The doors closed, sealing the openings of the slips in stormy weather and in winter.'

Secondly, the yacht Irene had to be moved back out, almost daily, for pleasure cruises and also for transporting guests to the then rail terminal at Clayton. Moving the yacht out of the building required firing up the steam engines inside the wooden structure. This was where another feature came into play. A metal funnel could be lowered to catch the steam and channel it up and out of the roof. This building-as-machine produced the smoke-belching spectacle that young Grant was so tickled to witness. Once the men had the steam power fired up, the tiered doors could be pulled open, and the yacht moved backward out of the yacht house under power.

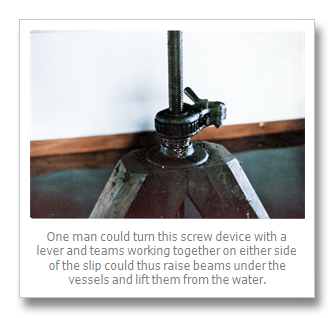

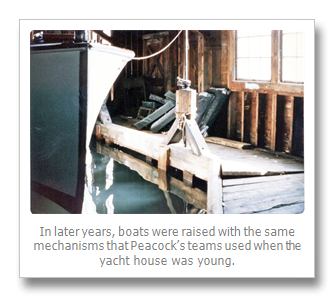

A further innovative feature of the structure resolved a difficulty associated with maintaining the yacht and the other water craft stored there.

'Each slip was equipped with apparatus to raise the boats including the yacht out of the water during the winter, and through the season if work on the bottoms was necessary,' Peacock recalled, adding, 'Attention was constant on the bottoms of the racing boats. They seldom remained in the water at night.' A machine shop ran across the back of the yacht house, at the head of the slips. 'The yacht and all family boats were kept immaculate,' Peacock recalled. The job of 'shining brass and maintaining teakwood decks was a never-ending task.' Peacock recalled an additional 13 boats regularly kept in the building. These included a 50-foot cruiser, service boats, skiffs and another pride of the fleet, the Pirate, a 39.5-foot displacement hull raceboat famous in the Thousand Islands for the plume of water it threw. Peacock could well remember being allowed to scamper around inside the yacht house, even climbing to the crew quarters and watching activities from a balcony there that overlooked the whole scene. 'It was a beehive all summer,' he said.

The various apparatus to which Peacock referred, which the men needed to raise the boats and even the weighty Irene out of the water, were ingenious purpose-designed mechanisms known as capstan screw lifts. These were something like giant corkscrews bolted in pairs at intervals along each side of each slip. Instead of raising corks from a wine bottle, they raised posts through the floor of the yacht house. Attached to the bottom of each of these posts were beams that spanned the slip of water. As the men cranked the screws up, the beams would rise beneath a boat and lift it out. Once the work was done, the boat was lowered back into its slip, and the beams lowered out of the way underneath it to be well submerged in the water below. The screws had flat lands, the engineering gift being that they turned around on a flat surface instead of up an incline.

I recalled that my brother, the Washington architect Darrel Rippeteau, had made a prophetic little booklet of photos of the Peacock yacht house at the time I was doing my research. He wrote of this unique structure: 'While the big barn, or yacht house, was plain on the outside, it was a structural tour de force on the inside. The main slip resembled the nave of a great cathedral with graceful wooden columns and massive doors. The columns shot aloft and curved inward to complete themselves as lovely arches carrying the steep roof. The clear space beneath the arches suited Peacock's tall ship.'

Eventually, the end came, hastened by the First World War. It was ironic that I came upon the notes from my interviews with Grant Peacock while searching for something else in our attic one recent day. It was an even 100 years since the Austro-Hungarian heir, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, was assassinated in June 1914, an event which sparked the war.

'Everybody went to war,' Peacock said, adding that his two brothers joined the military and in 1916, he himself entered the US Navy. 'We left the St. Lawrence as a family in 1916,' he said. Luxury yachts, once home to lounging ladies and race day enthusiasts, were commandeered by the government and sent to sea for scouting, hospital and errand services. Henry Laughlin's 200-foot yacht, the Corona, was converted to a hospital ship and stationed off France in the harbour at Brest. A second whammy, the advent of income tax with passage of the 16th Amendment in 1913, tore into the vast fortunes that had underpinned the socio-economic profile of that American Edwardian era following the Gilded Age.

Although the Peacock yacht house stood many years and was used for boat storage, it deteriorated and eventually burned. Its larger sister, the Boldt yacht house just downstream on Wellesley Island, was rescued and still stands. In my brother's Peacock booklet, the last gloomy image was captioned: 'When it is gone, we may not remember why we miss it.'

As I sat with Grant Peacock that spring day in 1974, the scenes gradually faded with the light and I made a move to conclude our afternoon. We stayed in touch for a while, his letters written in a distinctive hand. His last, dated July 23, 1975 talked of a recent hospital episode and of his inability to accept an invitation for a river visit. My sincere wish was that he could just sit back, relax and again conjure up the sights and sounds of that amazing morning seventy summers ago in the Thousand Islands.

By Jane Rippeteau Heffron

© Copyright Jane Rippeteau Heffron 2015, All Rights Reserved

The author was born and raised in Watertown, NY, spending summers in the Thousand Islands. She graduated from the University of Rochester and then earned a MSc degree at Columbia University’s Graduate School of Journalism. She was a reporter for The Washington Post in Washington, DC prior to joining Business Week magazine in New York City. When she and her husband moved to England, she joined the Financial Times, and later ran a publishing department for investment research at Citigroup. The family has a home on Wellesley Island.

This article was originally published in the October 1, 2014 edition of the “Thousand Islands Sun,” Clayton, NY.