Since the publication of ‘Secrets of Hog Island,’ in September 2015, some new information concerning the burial has come to light. Alex Lawrence, one of the owners of the west side of the island, contacted me and explained ‘the rest of the story’. She also supplied a copy of the archaeologist’s report: “Stage 4 Archaeological Mitigation, Hog Island Burial Disinterment, Leeds and the Thousand Islands, Ontario” prepared by Susan Bazely and Andrew Hill and produced in February of 2009.

Once the initial examination of the skull by forensic anthropologist Jerome Cybulski and the Stage 1 Archaeological Assessment by Andrew Hill, of the now defunct Cataraqui Archaeological Research Foundation (CARF), in June and July of 2008 were completed, the Registrar of Cemeteries indicated that the remains should be disinterred by an archaeologist and moved to an ‘approved cemetery’.

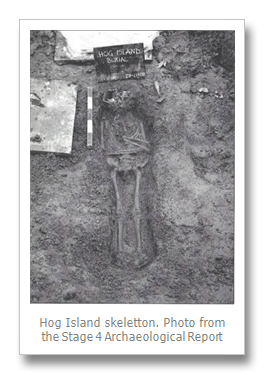

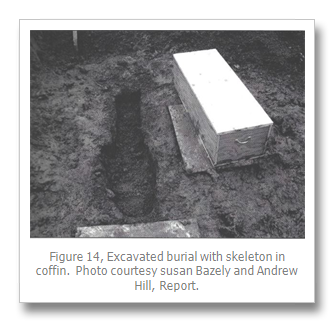

This was done 28 Nov. 2008 before the frost became a serious impediment. Susan and her colleague, Lindsay Dales, removed the protective covering and excavated the remains. It took several hours to carefully record and remove the bones and place them in a small plywood coffin. The fragments of coffin wood, the forged nails and a button were also placed with the remains. From the island the remains were taken to St John’s Catholic Cemetery in Gananoque for reburial. The rite of committal was performed by Father Shawn Hughes that afternoon. Father Shawn also acted as the representative of the deceased. For those interested, Jane/John Doe was buried in plot 64, row 52.

So far, so good. But what did the excavation turn up beside the bones? This is where it starts to get interesting. There were four discoveries:

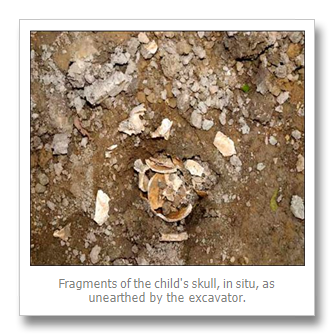

First, the remains, in situ (before they were disturbed by the archaeologist), measured 1.35 metres (4’5”). Allowing for some disarticulation of the bones it would be safe to say the child was a little over four feet tall. Susan estimated the child to be about 10 years old which tallies nicely with Jerome Cybulski’s estimate of 7-11 years based on his examination of the teeth. Not discussed in the report was whether the child was male or female. Due to its youth the normal indicators, skull and pelvis shapes, would have likely been inconclusive. And the skull had been badly crushed by the backhoe. The pelvis of a female grows differently from a male as puberty sets in as it must allow for childbirth.

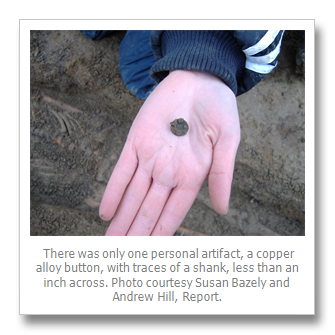

Second, there was only one personal artifact, a copper alloy button, with traces of a shank, less than an inch across, with no discernible markings. It was “…located in the throat area and probably fastened a shirt or possibly a cloak1…” and there was “…no further indications of cultural affiliation or possible indicators of date”. Sadly, this doesn’t help us to learn more about the child.

Third, and this is where the story veers in a new direction, there were small fragments of a coffin and forged nails. “Coffin nails initially appeared only at the head area, but gradually began to appear further along the west and east edges of the coffinii” How did the body of a child, in a coffin, get to the island? And why? On reading this my speculation gene went into overdrive. How to account for this? After reflecting for a while, two scenarios presented themselves.

In the first instance, the child died on the mainland, once settlers had arrived in the area around 1800, was put in a coffin and transported to the island for burial. But why do that when a burial on the mainland would have been so much simpler? There were already burial grounds in Gananoque, Lansdowne and at the now abandoned Stratton Cemetery less than a mile away. The early Cooks were buried there. By the early 1800s forged nails were on their way outiii, being replaced by cut nails. Cut nails were introduced in the late 1700s and were the first step toward full automation of the nail making process. This scenario, though possible, is very unlikely given the locally available burial sites.

In the second instance, the child died earlier than English settlement as speculated in the original article. French Habitants travelling to the Fort at Kingston would have had all the tools necessary to make a crude coffin from wood on the island. With axes, saws and some wedges they could have made rough planks from a couple of trees and fastened the planks with the forged nails they were bringing with them from Quebec. For someone raised in that time, especially farmers and settlers, this was the normal way to obtain lumber in the bush. The resulting coffin wouldn’t have been pretty but would have served the purpose. It also speaks to the reverence they had for the child. Instead of a simple shroud they took the time to make a burial box. Forged nails were the only type of metal fastener until the late 1700s. There were no known consecrated French burial grounds between Quebec and Fort Frontenac so we can imagine that river travelers would use the most convenient place for a burial of one of their party. It is easy to find baptisms and marriages in the records of established French Canadian communities but in the pioneering days of New France, settlers and voyageurs who died outside the existing French parishes of Quebec and Acadia, did not have their rite of burial recorded.

Fourth, and this is also puzzling, the burial was oriented north-south with the head toward the south. Normal Christian practice is for an east-west orientation. Anyone performing a burial would know east and west from the flow of the river as well as the rising and setting of the sun. It is hardly rocket science. Were the grave diggers just careless or was it for some reason we will never know?

If there are other bodies still buried on the island we will probably never know. The archaeologist, in her report, found no other indications of burials. The island, though, has undergone at least three changes in its landscape profile since English settlers arrived. In the 1820s the island was stripped of its trees to service the steamers. When Silas Cook showed up in the 1850s he cleared the remnants of the stumps, the new brush and the rocks and then plowed, removing any signs of the graves. In the 1990s the fishing lodge group, in their preparations for construction, regraded parts of the island. And finally, the construction in 2008 again altered parts of the landscape.

Even in 1873, when Charles Unwin, the surveyor, visited the island he was unsure of the number of graves. The terrain had already been altered by Silas to make way for his market garden so it appears Unwin only reported on what Silas had speculated. Here again is what Unwin wrote: “Nearly all cleared, fair soil, has been ‘cropped’. There is a small shanty on it and two or three graves.” The lack of any other historical references leads to a great deal of uncertainty about other graves being present.

In the Summary and Recommendations section of Sue Bazely’s report (page1) she covered any eventuality, by using a ‘boilerplate’ recommendation that a further archaeological assessment be done prior to any further construction activity. And, if any new evidence of human remains is discovered the Registrar of Cemeteries must be notified immediately.

On the positive side, we now know that the remains of the child are safely reburied in consecrated ground. On the negative side, there were no conclusive grave goods that could firmly date the burial. We still don’t know the child’s story and probably never will.

[i] Both quotes are from page 23 of report.

[ii] Page 22

[iii] The timeline for the disappearance of wrought/forged nails isn’t as clear cut as I would like. Their use continued into the 1800s although they were used less and less as time went on. As the price of cut nails dropped, the use of forged nails decreased. Susan Bazely, in an email exchange, noted: “It might be worth mentioning that wrought/forged nails were in use well into the 19th century. Jennifer McKendry has prepared a chronological summary of nails for sale, in the various Kingston newspapers, through the 19th century and wrought nails are available for sale from 1817 to 1873. The first archaeological evidence I have for cut nails is 1822 at the Naval Cottages, but we know they were specified for use at all British Naval Dockyards from 1812 on.” As a note of interest, forged nails can still be purchased through specialty suppliers.

By Paul Coté

Paul Coté is a resident of Gananoque. He has socialized and worked on the River for most of his life. History has always been a passion and he is a self confessed genealogy addict. Recently retired from contracting on the River, he now has time to pursue and write about his research. He is currently writing a book about the 500 year history of the Leeder family and shared some of that history in My Favourite Ancestor, August, 2015 and Secrets of Hog Island, appeared in our September 2015 issue.