Before we think about the lighthouses, let’s settle the nagging question of which came first: the name or the fiddler? People more knowledgeable than I about the Thousand Islands have been caught on this question, declaring truth to be stranger than fiction. Sadly, the truth is usually fairly mundane . . .

The record has been set straight in the past. On August 30, 1890, the Gananoque Reporter announced:

“Chauncey Patterson Drowned. On Friday evening of last week [i.e., August 22, 1890] Mr. Chauncey Patterson, a blind man who lived on an Island just at the upper side of the Fiddler’s Elbow, was coming out of Alexandria Bay in a skiff. He was rowing, and his son-in-law was sitting in the stern directing him. The steamer Junita was going into the Bay, and ran the skiff down. Patterson not being able to see, was unable to avail himself of the life buoys thrown to him, and was drowned. The young man caught hold of the steamer, and was drawn aboard without injury. Patterson’s body had not been found at last accounts. He was accustomed to play on the fiddle, and by many people this accomplishment was held to account for the name, Fiddler’s Elbow, given to the two short turns in the channel near where he lived. But it had nothing to do with that. The Fiddler’s Elbow received its name before Patterson was born. A few years ago [in 1881], [American tour-boat operator] Capt. Visger, of the Island Wanderer, engaged Patterson to appear under a canopy upon the high rocks of an island next to his, and play the fiddle every day as the boat passed. This led still further to the association of him and the Elbow in the minds of tourists. And some people got in the way of calling the locality the Blind Fiddler’s Elbow.

The fictional version apparently sounds the better of the two versions for beguiling tourists, however, so it has lived on like Zavikon’s “shortest international bridge” (both sides, of course, being in Canadian waters), which is still celebrated on postcards and boat tours.

The name of the Fiddler’s Elbow area, then, most likely arose from the bent-arm shape of the narrow passage between Ash and Wallace Islands. In The First Summer People, author Susan Smith states that it was named in the eighteenth century, by sailors who traversed the region in bateaux. Certainly, when the spate of lighthouse construction began on the Canadian side of the Thousand Islands in the mid-1800s, the name was already accepted. In 1856, lighthouses were constructed at either end of the passage. Listed, east to west, as “Fiddler’s Elbow” (near Wood Island) and “Lindoe Island” lighthouses, each was a white, square, wood structure.

Fiddler’s Elbow Lighthouse

Both of these lighthouses are now gone, but the Fiddler’s Elbow Light is easily the “most forgotten” of the Thousand Island lighthouses. Early mentions in the Journals of the Legislative Assembly for 1852 – 53, include Fiddler’s Elbow and “Lynedock Island” in a list of nine lights that are to be “located in the most intricate parts of the River.” By 1856, the lights were operational and lightkeepers had been engaged. But no sooner is this achieved, than its days were numbered. The 1857 the Journals of the Legislative Assembly announce:

“It is proposed to remove the framed light-house now standing on “Fiddler’s Elbow” to “Hemlock Point” on Wolf [sic] Island, about midway between Gananoque and Kingston, a recommendation to that effect having been made by the captains of the steamers generally.”

As mentioned in my article on the lighthouses of Wolfe Island (November 2009), given the time and distances involved, it does not seem probable that the lighthouse actually was moved to Wolfe Island from Fiddler’s Elbow. More likely, the structure was dismantled and the materials were put to use elsewhere.

James Landon received a salary of £ 22 s. 10 for acting as lightkeeper at Fiddler’s Elbow for the year 1856, and John Landon a salary of £ 35 for 1857. It is not certain that there were two different lightkeepers, however. The early records have many inconsistencies and errors. Regardless, after 1858, there is no further mention of Fiddler’s Elbow Light or any lightkeepers.

The dearth of information might have left us with nothing more than the knowledge that a small wooden lighthouse had once existed at the east end of Fiddler’s Elbow, but in 1952, the List of Lights and Fog-Signals on the Inland Waters mentioned the Wood Island lighthouse, recording its original year of establishment as 1856. Details in the list suggest that Wood Island light was established in the same location as the original Fiddler’s Elbow lighthouse around 1937, after the Wood Island Gas Buoy (established 1928) was deemed inadequate. By this time, the Lists of Lights provided latitude and longitude information for each lighthouse, along with the classic “white, square, wood” description. This allows us to fairly accurately determine where the Fiddler’s Elbow lighthouse was set, on a small island just off Wood Island.

|

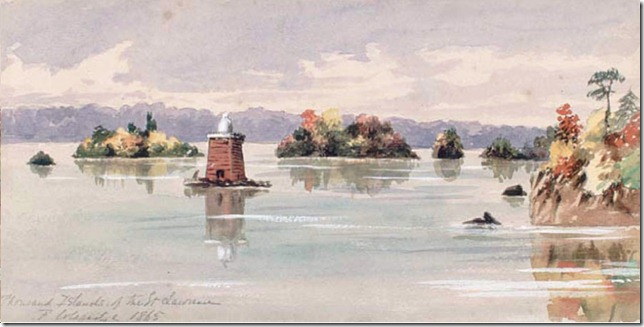

“Thousand Islands of the St. Lawrence,” painted by Francis Coleridge, 1865. In the collections of the National Archives of Canada. Online MIKAN No. 2836809. Could this be an image of Fiddler’s Elbow Lighthouse?

|

No identified images of the Fiddler’s Elbow light have been found to date, but I invite the readers of Thousand Islands Life to speculate on the image above. The artist is Francis Coleridge, and the painting is dated 1865. A British officer, Coleridge’s image is clearly a Canadian lighthouse, and is identified as being in the Thousand Islands. As far as I can decide, reasonable candidate lighthouses are: Fiddler's Elbow, Jackstraw Shoal, or Spectacle Shoal. These are Canadian lighthouses that had been built by that date in the Thousand Islands and that cannot be dismissed for other reasons. Of course, it should not be Fiddler’s Elbow if this was painted from life, as the light was discontinued several years before 1865, but it has been suggested that this is the Wood Island area, and there are discrepancies with both the Jackstraw Shoal and Spectacle Shoal options as well. Then there is always the question of artistic license . . . Still, it is fun to speculate, and I challenge readers to help settle the question.

Lindoe Island Lighthouse

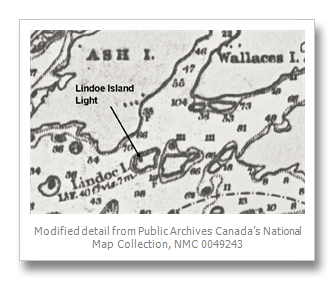

At the west end of Fiddler’s Elbow, Lindoe Island has been spelled variously as Lindoe, Lindoc, Lindon, Lyndoc, Lyndock, Lynedock, Lynedoch and Lyndoch, the last of these being the name it carries today as part of St. Lawrence Islands National Park.

In the Unwin survey of 1874, Charles Unwin identified it as Island 79. A small island, 1.4 acres according to Unwin, it was described by him as “rock, with a few trees and brush.” The lighthouse was set on the north side of the island, and was known for its early history as the Lindoe Island Light, though this gradually gave way in the 1920s to the Lynedoch Island Light, and eventually to the current Lyndoch Island. The lighthouse has also been referred to locally as the Fiddler’s Elbow lighthouse – logical given its location at the west end of this channel, but most confusing to the researcher trying to find information about a different lighthouse by that name.

Built in 1856, the tower 26 feet in height, Lindoe Island lighthouse lasted many years longer than its eastern counterpart. It, too, was a small, white, framed wooden structure, with three base-burner lamps, and stood some 40 feet above the high water level. It was watched over by several different lightkeepers over its lifetime. Joseph Landon received a salary of £ 22 s. 10 for acting as lightkeeper at Lindoe Island for the year 1856, and William Landon a salary of £ 12 s. 10 for 1857 (possibly an error in amount as no other keeper is listed for any part of 1857). As noted above, the early records have many inconsistencies and errors, but as far as the records go, there were four different Landons acting as lightkeepers in the Fiddler’s Elbow area over these two years! We know a little more about some of those who followed.

J.W. Allan (1858 – 1861): paid $70 in 1858 (while $321.12 was spent for supplies and repairs), his salary increased to $140 the following year. By 1860, the government got around to building a lightkeeper’s dwelling Also this year, the decision was made to change the fuel from sperm whale oil to coal oil, and by 1861, it was in place and working well: “more economical, and gives a steadier and more brilliant flame than fish or animal oil.”

Nathaniel Orr (1860 – 1861): assistant, then sole lightkeeper during the change-over to coal oil, Mr. Orr did not remain long at Lindoe Island. He was appointed lightkeeper at Snake Island in 1868. He and his wife (Eliza Deryaw) died in May 1888, both of pneumonia resulting from falling through the ice after a trip back to the island from Kingston. Their son William B. Orr was appointed as the succeeding lightkeeper.

John Wallace (1861 – 1881 June): overlapped briefly with Nathaniel Orr, likely training with him for the position; John Wallace acted as keeper for the next 20 years. His annual salary of $140 rose to $250 by 1867, then remained unchanged until his retirement in 1881. Government inspectors who visited and brought supplies on July 7, 1876, reported that the lighthouse needed painting and a new, larger lantern. They noted that John Wallace had a family of seven, and that he kept the light clean and in good order. Nearby Wallace Island, where he and his family lived, is named after the lightkeeper

John Gerrard Wallace (June 1881 – 1904): One of John Wallace’s sons, John Gerrard Wallace took over as lightkeeper in 1881, at the same salary of $250 per annum, keeping the tradition in the family. The following year, $35 was spent for a boat and $140.33 on materials and labor for building a boathouse. In 1893, buildings at the station were repaired, and a new boat supplied, at a cost of $86.50. General repairs to the dwelling (on Wallace Island) were made in 1894 ($41.50).

Manley R. Cross (1904 – December 1907): 1903 saw experimentation with acetylene as a fuel, with the intent to make the lighthouses “practically automatic.” And in 1904, the services of the keepers of the lights at four of the Thousand Islands lighthouses, including John Gerrard Wallace at Lindoe Island, were dispensed with. Manley Cross, formerly lightkeeper at Gananoque Narrows and Jackstraw Shoal lighthouses, became the sole keeper of six lighthouses, at an annual salary of $480.00. Manley Cross died in December 1907.

(Mrs. Manley) Jeanette Cross (January 1908 – May 1912): Despite the unanimous recommendation of the Reform Executive for Lansdowne Front that Manley Cross’s son Milton be appointed lightkeeper, his widow Mrs. Manley (Jeanette) Cross was appointed. At a time when women were not eligible to vote, and were not considered to even be “persons” in the eyes of the government, Jeanette Cross had sole charge of six lighthouses for four years. She is the only woman to have acted as lightkeeper in the Thousand Islands for more than a few weeks. She was paid $550.00, then $600.00 per annum, as the government was forced to improve salaries when faced with the increasing difficulty of securing staff. In May 1912, however, the government reverted to coal oil as the fuel at the Thousand Islands lighthouses, “for reasons best known to themselves,” necessitating more work, and resulting in the recall of the dismissed lightkeepers. Mrs. Cross continued to act as lightkeeper at Gananoque Narrows and Jackstraw Shoal for another two years.

John Gerrard Wallace (May 1912 – 1918): returned to the position of lightkeeper he had held previously on the return to the use of coal oil fuel, but was now paid $380.00 annually. He remained for a further six years, bringing the Wallace family’s years of service as lightkeepers on Lindoe Island to 49 years, exceeded only by the Gillespie family on Wolfe Island and the Root family on Grenadier Island.

P. Taylor (1919): Information sources by this time become sparing with details on lightkeepers. P. Taylor was paid $261.98 for his services.

T.R. Turkington (1919): See above. T.R. Turkington was paid $44.84. There is no information on which of these lightkeepers preceded the other.

Andrew Truesdell (1920 – August 1937): Paid $450.00 annually, then $480.00 from 1923 on. The number of lightkeepers in the Thousand Islands was dwindling rapidly at this time, with various expenditures for “removal of lightkeeper” in government accounts. Andrew Truesdell was paid $162.58 for April 1st to August 2nd, 1937, after which the light became an unwatched light. A significant alteration to the lighthouse in 1937, the first recorded at Lindoe Island, was most likely related to this changed status.

The unwatched lighthouse continued as a navigational aid for many years. Further alterations were recorded for 1939 and 1946, the latter most likely its conversion to electric lighting. Another alteration is recorded in 1955, likely the last before the old tower became one of several demolished by the Coast Guard in 1967. Ironically, the old structures were pulled down in an effort to “beautify the River” in celebration of Canada’s centennial! The removal of the lighthouse was easily accomplished, as the structure had deteriorated over the years. As described by Coast Guard employee Chuck Lemaire, the Coast Guard ship Simcoe was brought to the site, a rope was put around the tower, and it was simply pulled off its footings.

The Lyndoch Island light (or light number 363) continues to act as a navigation aid today. After another refit in 1984, it is described in the 2009 List of Lights as a “white cylindrical mast, green upper portion.” Useful, without doubt, but somehow the magic is gone.

By Mary Alice Snetsinger, ecoserv@kos.net

Mary Alice Snetsinger is a conservation biologist now working in Kingston. She grew up in the United States and Canada, and worked for four years at St. Lawrence Islands National Park. She became interested in the 19th century lighthouses of the Thousand Islands in 1997, and has sporadically researching them ever since. In November 2009, Mary Alice provided TI Life with Wolfe Island’s Lighthouses. She would welcome hearing from any reader with more images or stories of these or other Thousand Islands lighthouses.