The Restoration of a Que’ Sara, a 1932 18’ Gar Wood [Click to enlarge photos]

The dust covered little Gar Wood runabout sat looking like the definition of a basket case in the street level shop at Van’s in Alexandria Bay. Obviously, the restoration process, under the careful stewardship of master restorer Rich Jury, had ground to a halt for reasons I would only uncover weeks later. Her classic lines had caught my eye as I walked through Rich’s shop, but I knew not to inquire about why progress on her restoration had stalled unless I wanted to get pulled into a project I was not ready to undertake.

Gar Wood, the legendary industrialist – turned – raceboat - designer and driver, as well as head of the boat building firm bearing his name, was aware that the boating market was falling victim to the effects of the depression by 1931. In an attempt to rescue his company from a substantial decline in sales volume, he worked overtime with his designers to develop a completely new boat concept. The 18 foot boat would be built as affordable as possible, while maintaining the stylish design and good handling characteristics that Gar Wood had become well known for over the past few years. He hoped the twin cockpit model would sell well enough to keep his boatbuilders employed. Tony Mollica writes that Gar Wood received 43 orders for their new 18 footer at the 1932 New York Boat show, more orders than the company received in 1931 for all combined models.

Gar Wood Hull Number 4270, destined to become our Que’ Sara, had arrived at Rich’s shop after a trailer ride up I-81 from Binghamton. The owner had purchased her from a New Hampshire based boater, who had owned her for several years and kept her in running condition. Tony Mollica, President of The Gar Wood Society, documented that Hull # 4270 had been delivered to Stearns Marine Company, Boston, Massachusetts, after being shipped on May 12, 1932. She was the 25th hull of the 106 made in this series of runabouts in Marysville, Michigan.

By the time the boat had been delivered from the Binghamton owner, she was in need of some serious repairs and restoration. Rich Jury’s reputation as a master restorer, and honest businessman, reached the ears of the owner and an agreement was made for Rich and his assistants to start work. His first order of business was to complete his own survey of the hull. This generally encompasses several circumnavigations of the boat, with a small hammer “thumping” on the planks, transom, and chines while listening for telltale sounds of soft wood. This process is accompanied by strategic prodding of suspect areas with a sharp knife or ice pick. In short order, it was determined that the little Gar Wood had several planks and a three foot section of the keel that needed replacing. In addition, multiple ribs and frames – the large “ribs” that form the shape of the bottom – were soft or rotten, and had to be replaced. The king plank, the wide board running down the middle of the deck, was split from an improperly tightened lifting ring.

This major structural work of replacing planks and part of the keel and deck necessitated stripping the hull of all of her hardware, windshield, engine, and the propeller and running gear – including the gas tank. By the time all these components were removed, the definition of the term “basket case” became apparent to any observer. Parts labeled with notes on masking tape were stored in baskets, cardboard boxes, and in corners of the shop. Coffee cans, baby food jars, and odd sized soup and tomato cans were filled with various size screws and fasteners to be reused in the reassembly phase of the project. The rotten and damaged planks were unfastened one screw at a time, with the goal being to remove them as patterns to be used in shaping the replacement planks.

The gas tank was carefully removed for inspection and cleaning, and the six cylinder Chrysler Super Crown engine was pulled and stored for the duration of the project. Once the boat was stripped of her hardware, engine, and gas tank, the empty hull was lifted and rolled over. Rolling a boat requires skill, equipment, and teamwork. A steel lifting frame is erected over the hull, and chain falls are attached to straps wrapped around the hull. One side of the hull is lifted into the air at the same time the other side is lowered. If perfectly coordinated, the boat will literally roll over onto its back with very little manual lifting or pulling required. Once the boat is upside down and securely blocked on its deck, the work of removing the keel and bottom planks can begin. Then the real craftsmanship of the restoration is ready to get started.

After planing boards of mahogany to the same thickness as those removed from the bottom and sides, Rich cut new planks to the shape of the pattern planks. This is followed by the painstaking final shaping of the new boards, which is all done using hand planes and sanding. Once the new planks are perfectly shaped, the process of fitting and bending the boards to the form of the boats frames and ribs takes place. It is not unusual to have to steam a plank or rib in a steam filled piece of pipe to make it limber enough to allow the carpenter to fit and bend the board to its required shape and form. The plank is then fastened to the hull with several screws at one end, and slowly pulled or twisted into shape with the help of clamps and screws. This process can take days of patient tightening to allow the plank to conform to its new shape without breaking or splitting. Once the new section of keel had been installed, the time consuming boring of a new shaft hole and fitting of the shaft hanger and rudder needed to be completed before the boat could be rolled back to the upright position.

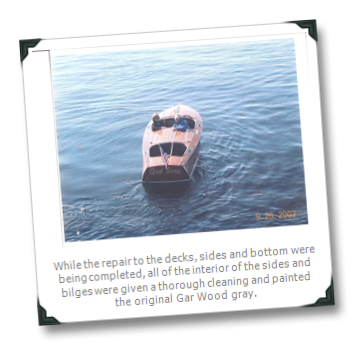

The selection of a beautifully grained piece of wood for the king plank on a varnished runabout is an opportunity for a restorer to work some creativity into a restoration. Extending from the bow to past the windshield on this particular model Gar Wood, the king plank was stained a darker contrasting tone and exhibits beautiful grain through its luster. Early Gar Woods exhibited a signature pattern of contrasting dark stains on their king planks and covering boards (the planks on the outside of the decks), and the gleaming varnished contrast catches your eye as a Gar Wood slides or races by in the water. Rich found the perfect piece of mahogany for his replacement king plank, and lovingly installed it as the hull started to come back together after weeks of hard work. While the repair to the decks, sides and bottom were being completed, all of the interior of the sides and bilges were given a thorough cleaning and painted the original Gar Wood gray.

Very few people have the patience and vision to successfully complete a restoration of this scale, although many people attempt them. Therefore, it is not unusual to see advertisements for “project boats” in wooden boat magazines that were started as restorations but soon abandoned as the magnitude and the expense of the project hit home.

Quite a few wooden boat restorations hit a point when the owner becomes exasperated with the time and costs involved, and the little Gar Wood fell victim to this syndrome at this point. The owner quit paying Rich for his work, and before long, the basket case boat was gathering dust and being pushed to the back of the shop. Other boats whose owners were paying for completed work took priority for Rich’s time and woodwork.

After watching dust and spider droppings build up on the little Gar Wood’s decks for weeks, I cautiously approached Rich about the delay on the project. Upon hearing his dilemma, I contacted the owner and casually asked if he was interested in turning the project over to me at a fair price. After a protracted negotiation, we agreed on a deal that would make Rich and his crew whole on their past work on the boat. I was as excited as a kid at Christmas to have a “new” boat project to work on, and Rich and I quickly agreed upon an estimate and plan for completion. The concept was based on his expertise and my manual labor on the sanding, scraping and cleaning, as well as doing any prep work on the varnish I was qualified to complete. I knew I had a strong and enthusiastic assistant for the project in our daughter, Sara (hence the name Que’ Sara) to help with the hard work of scraping and sanding as well as plugging the screw heads with mahogany bungs. Steve Keeler, one of the owners of Van’s, would take charge of the mechanical work of hooking up the engine and rewiring all of the electrical components. I felt like we had the team to reassemble the basket case, and was anxious to get to work.

The first phase of our plan was sanding and preparing the bottom for caulking and painting. I dove right into my assignment, and had been sanding away for about five minutes when I made a sickening discovery. The first plank I was sanding had a rotten spot, and would have to be replaced. Most wood boat owners know the pain and expense the discovery of a rotten plank causes, and the fact that it can happen no matter how well a boat is maintained or surveyed. Rich felt horrible about this unanticipated repair, but quickly went to work fashioning the new plank. As luck would have it, the plank was the most difficult board to replace on the entire boat – running from flat on the bottom and twisting almost 90 degrees as it rose to the side. However, after five or six days of steaming and patient bending of the plank, it was successfully replaced and looked as good as new.

While Rich worked on the plank, Sara, Steve, and I went to work sanding the rest of the boat. We had to tape and prepare the deck seams for caulking with the white sikaflex putty that gives the decks their distinctive lines running fore and aft. Mahogany plugs were cut and installed in the deck and planks to cover the screws fastening the boards to the frames and ribs. And we sanded and sanded…

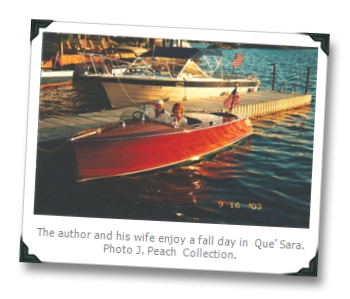

As the work progressed through long days and nights, I became focused on launching the boat in time for Sara to have a ride prior to her return to fall classes at Hamilton College. My wife, Pat, had come up with the name Que’ Sara, and spent an enjoyable couple of hours with Rich as he chalked out the script he would hand letter in gold leaf on the varnished transom. Steve plugged away at the mechanical challenges of reassembling a seventy five year old boat. By late August, we had put three coats of varnish on Que’ Sara, and had been soaking the hull with a hand sprayer and hose nozzle while still on the trailer. Steve pronounced the engine ready to run after firing it up in the boat using a water hose to provide cooling water. Rich felt the boat, while a long ways from being complete, was ready for a sea trial. The weather forecast was calm for the next morning, so Steve and I made arrangements to launch the little Gar Wood at seven am from Crossman Street in Alexandria Bay.

It is always nerve wracking when you launch a freshly restored boat for the first time, especially knowing very little about her engine. However, the launch went well, the bilge pump worked, and the engine started. Steve and I motored out of the bay in the calm of the early morning, and were pleasantly surprised at the performance of Que’ Sara as we slowly increased the power from the old Chrysler. I quickly put in a cell phone call to Sara, and instructed her to hurry down to our dock, where we would pick her up on a cruise by our Island. I told her to be prepared, as we did not know much about the reverse gear in the boat, and may have to coast to a stop.

One of my favorite pictures of that summer show Sara and me side by side on our first run. The boat had no windshield or lights, but the smiles on our faces were from ear to ear. Our maiden voyage was only a few minutes, but was the first of hundreds of trips that we and our friends have taken throughout the 1000 Islands in Que’ Sara. We ran her back to the shop, and spent the next few days completing her restoration. That included several more coats of varnish, installing the windshield, navigation lights, horn, and all of the finishing touches that have made Que’Sara an award winning boat at local boat shows. She is still our favorite boat, and runs almost daily from May through October in the 1000 Islands.

By John Peach

John Peach and his wife, Pat, live on Huckleberry Island near Ivy Lea from May through October. The rest of the year they reside in Princeton, NJ, although John continues to make frequent return visits to the Islands throughout the winter. Their children, Sara and John Jr. visit as regularly as their careers allow. John retired several years ago from his career in international business. His family has owned a place in the Thousand Islands for over 50 years. John is a past president of Save The River, and is still active on the Save The River board.