Joseph Brant

Thayendanegea’s father, a prominent warrior, died when his son was an infant. A protogé of Sir William Johnson, a wealthy land owner, trader and Superintendent of Indian Affairs for the British Indian Department's Northern District, the young Mohawk, taking the English name, Joseph Brant, was educated in English at Moor's Indian Charity School in Lebanon, Connecticut, the forerunner of Dartmouth College, where he studied with the Reverend Eleazar Wheelock. Johnson planned to send Brant on to King's College [Columbia University] in New York City, but the outbreak of Pontiac's Rebellion upset these plans and Brant came home, since Johnson thought it was not safe for Brant to be at that college.

Joseph Brant was said to be "of a sprightly genius, a manly and genteel deportment, and of a modest and benevolent temper.” Brant became employed teaching the Mohawk language to fellow scholars planning on working with the Indians. Later he became a government interpreter with Indian Affairs. He teacher of Mohawk, and collaborated with Rev. John Stuart in translating the Anglican catechism and the Gospel of Mark into the Mohawk language. Joseph Brant became a lifelong Anglican.

Mentored in his youth by Sir William Johnson, Joseph Brant initially seemed destined to become a Christian missionary. Instead, Joseph was drawn to becoming his successor as liaison between the crown and the native people. His role was more than diplomatic negotiator, however. By the time of the Revolutionary War, Brant was a political and military leader, renowned for his exploits. Although accepting a commission as an officer of the British army, Brant in practice played the role of an independent war chief of a sovereign native nation.

Molly's Mohawk name was either Koñwatsiãtsiaiéñni, Gonwatsijayenni, Degonwadonti or Tekonwatonti according to different sources. Mary (Molly) Brant was the older sister of Joseph Brant. The siblings took the surname of their stepfather, a friend of Sir William Johnson. The family dressed in European style, residing in a substantial houses in Ohio and Canajoharie, New York.

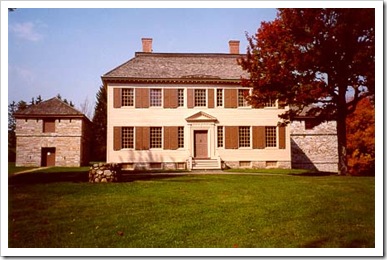

Molly became the mate of Sir William Johnson, Superintendent of Indian Affairs, who also lived in the Mohawk Valley and was central to the British concerns over colonial expansion. Formally (in British circles) Molly would be Lady Mary--possibly Lady Mary Brown--but not Lady Mary Johnson, since marriage between Native Americans and a British official could not recognized officially.

William and Molly lived inter-culturally. While Molley might receive distinguished guests dressed in satin, William might strip and appear mostly in war paint.

William and Molly had eight children. Widowed Molly survived Sir William, retaining considerable power due to her influence over the Native American allies of the British. After death of her husband in 1774 Molly gained more influence, in fact, than Joseph Brant, her more famous brother. She was not merely an eminence gris, advising behind the scenes, but Molly joined Joseph in field action; in 1779 both led attacks against the Revolutionary Army.

Cessation of hostilities at Yorktown in 1781 rendered the Loyalist Native Americans a nation without a homeland. The British ceded the Indians' traditional territories to the United States. Rather than abandon the Mohawk Valley, Joseph and Molly continued to fight on against the United States until 1783. Defeated that year at Johnstown, their forces retreated to Oswego, from whence Joseph moved his people to Canada farther west, whereas Molly and her supporters found a haven at Carleton Island, still a British facility.

Joseph Brant moved in elite circles. In 1792, Brant was invited to Philadelphia where he met President Washington and his cabinet. In February 29, 1776, he was presented to King George III and his queen at court. Reportedly, he proudly refused to kiss the hand of the king, stating that he was an emissary of the Six Nations. They were the King's allies and their own sovereign nation, not royal subjects. Joseph did, however, gallantly kiss the hand of the queen.

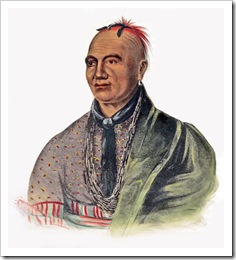

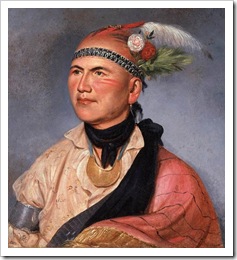

In England, fashionable painter of late 18th-century English society, George Romney, painted Brant's portrait. Typically, Romney avoided any suggestion of the character of the sitter. The artist's great success with his society patrons depended largely on just this ability for dispassionate flattery. In London, Gilbert Stuart painted Brant's portrait at least twice, once as reproduced at the outset, above, and again.

Historians have been puzzled about Joseph Brant's qualities as a leader. Clearly he evidenced great personal charisma. In particular, the question has not been answered as to why so many white Loyalists chose to join Brant's Indian forces rather than serving with British units. This was a dangerous game, for if captured by Patriot forces, Brant's white Loyalists would be regarded as traitors to their race and probably executed on the spot--much like soldiers who put on the enemy uniform. Regardless, Brant was able to retain a substantial component of white Loyalists in his ranks--no doubt a tribute to his unique leadership style.

After the war, when Brant established a thriving community, Brants Town, at Grand River near modern Hamilton, Ontario, he similarly attracted many white Loyalists to join his Indians as settlers. Brant was not so much the native nationalist as to discourage integration. Indeed, his accommodation of white Loyalists contributed to the failure of his dream, to establish a sovereign native nation in Canada. Failure of the British to fulfill promises embittered him, and a government "reservation" had to be accepted in lieu of an autonomous nation. Brant had simply backed the losing side.

![Joseph Brant, by William Berczy, 1797 [1794?]. National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa. Joseph stands on the banks of the Grand River, where he established his native Loyalist settlement. Joseph Brant, by William Berczy, 1797 [1794?]. National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa. Joseph stands on the banks of the Grand River, where he established his native Loyalist settlement.](../../../../../../../../Portals/Properties/images/News-Articles/2008/Nov-photos/WLW-JosephandMollyBrantcompiledbyPaulMalo_FD8C-NAC_thumb.jpg)

Molly Brant

In contrast to her brother, Molly Brant left no known portrait, but is equally remembered as a key historical figure.

"Tekonwatoni, known as Molly Brant, the Mohawk wife and then the widow of Warraghiyagey (Sir William Johnson) was a major military commander; she controlled the Indian armies that, as allies of the British, fought the revolting whites, decimating the Mohawk and Wyoming valleys. 'One word from her,' wrote the colonel officially in charge of his Majesty's Indian Forces, 'goes further with them than a thousand words from any white man without exception." James Thomas Flexner, Lord of the Mohawks

As mentioned, Molly's brother, Thayendanagea, [Joseph Brant] also made Fort Haldimand his headquarters. Large numbers of Loyalist tribes encamped on Carleton and Wolfe islands. The bloody massacres of the Cedars, Wyoming, Cherry Valley, and Stony Arabia, were instigated here by Joseph and Molly, executed by their forces which went from here.

The poet Maurice Kenny, a Mohawk like Molly Brant, and "perhaps the dean of American Indian poets" [Robert L. Berner, World Literature Today] was born in Watertown, New York, and so has geographic as well as cultural ties to Molly Brant, her brother, and their times. His volume, Tekonwatonti: Molly Brant, provides a sequential narrative of poetic fragments, mostly heard in Molly's voice, combined with historical notes:

Molly

by Maurice Kenny

Behind me,

the warriors,

young and fearless,

handsome in their war paint,

proud in stance,

strong in limb and mind,

spirit at ease as their

moccasined feet

pad the earth they follow

to protect and preserve.

|

War!

by Maurice Kenny

Will we never be without it.

Oh, Willie, I need your guidance.

Whisper the message of your knowledge.

Hold my trembling hand,

see with my eyes

the precarious path, danger, obstacles.

Reach into my tension,

clean my mind, make my thought

as clear as the waters of this pool

my warriors pass at dawn.

|

Posts

by Maurice Kenny

With pots of red paint and black

I went to the post in the center

of the village. With sticks

I dabbed paint on the fresh post

this morning brought from the wood

and placed at noon in earth.

After council

the war chief will stride

out through the door of the longhouse

into starlight

and as drums commence to throb

and feet move circling the post

he will thrust his sharp blade

|

|

I, too, am proud to lead

to lead these young men

to battle, victory--perhaps death.

In death their blood

will scar my hands forever;

The tears and keening of their women--

mothers, wives, daughters--

will ring always in my ears.

The loss will be too great to bear.

|

Give me good sense

so I my not waste

a single drop of the blood

of these young and brave

who fight for England now

but truly for the survival

and strength of the Longhouse

which you so deeply admired.

|

into the soft flesh of the head

His warriors will dance,

firelight will flame high

and these avowed brave men will follow

the lead of Brant

and thrust tomahawks

into the weakened post.

Red paint, and black,

will splinter and spill.

In the dawn women

will find chips on the ground

suggesting enemy blood.

|

| |

|

The war post fired

in blood and black paint.

One knife stood

straight in the head

of the post.

|

When counted in 1783, more than five-hundred Loyalist Indians we living on Carleton Island. These warriors, led by Joseph and Molly Brant, were joined by others encamped on nearby Wolfe and other islands, preparing to attack the Revolutionary forces in the Mohawk Valley. We may imagine the tension of the night as "drums commenced to throb," and "it is not to be wondered at ... when from many sources we hear of the drunken orgies held by the Indians on Carleton Island."

"Molly's dark indian eyes disguised fierce passions. She hated with a violence. Once she demanded the head of an enemy so that she could kick it around the room."