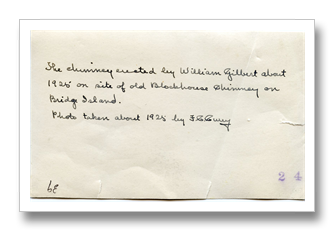

Editor's Note: The present chimney is the third built on the island. The first dates back to 1799, when the French were travelling back and forth to Montreal and Quebec from the Great Lakes. The story of this chimney is a romantic one that has been told in several early histories.

The island was named Bridge Island in 1818 by Captain William FitzWilliam Owen on his British Hyrdrographic Survey. Today the island is known as Chimney Island and is a private summer residence.

The following piece, ”The Romance of Chimney Island” was written in 1914. by Frederick Curry. It was published in The Canadian Magazine of Politics, Science, Art and Literature. Vol. XLII, November 1913 to April 1914. (Toronto, The Ontario Publishing Company Ltd. 1914.)

The Romance of Chimney Island

Oddly enough in the short space of twenty-five miles of the St. Lawrence there are two islands that dispute the title of Chimney Island. These are Bridge Island, some eleven miles above Brockville, Ontario, and Isle Royale, two and a half miles below "Windmill Point, Prescott, Ontario. Naturally, the history of the two islands, one of which is in Canada, and the other (Isle Royale) in the United States, has become somewhat confused. To present the romance and history of these two islands and possibly straighten out this confusion is the object of this sketch.

Isle Royale originally bore the Indian name of Orakouenton, a name also bestowed upon Levis by the local tribes, when he fixed on that island, on August 26th, 1759, as the site of the fort which afterwards bore his name. Levis gives the meaning of the name to be Le Soliel Suspendu (Hanking Sun, or, more freely, Hanging Fire). Just here it is interesting to note the various names then in vogue for well-known points along the riverfront.

Ogdensburg was then Fort La Presentation: Prescott, La Callete [sic probably La Gallete]; Maitland, Pointe au Baril ; Brockville, or some point above it, Pointe au Pins. Jones Creek, the Otondina or Toniata River; Gananoque, Onnondokui, or, as the French spelled it, Gananonkui; while Kingston, once Fort Frontenac, took its name from the river emptying there and became Catarakoui. [all names often have different spellings]

The various attempts to render the Indian names phonetically in French gives rise to many variations of these most of which can easily be recognized from the above list, which is an extract of the itinerary of one of the Jesuit brethren, Father Potier, in passing from Montreal to Detroit, in 1744.

Fort Levis, on Isle Royale, was part of a series laid out by the French engineer, Desandrions, in 1759-60,and was a fairly good piece of engineering, being defended with an abbatis around the entire island and both wet and dry ditches, as well as the usual parapets and stockades. It was the scene of one of the last engagements between the French and English, and was leveled by order of General Amherst. The tall chimney stood for many years, until finally the hand of time completed Amherst's work, so that all that now remains of Fort Levis is the tumbled lines of the ruined earthworks barely visible from the passing steamers. [see TI Life’s 1760 "Battle of the Thousand Islands", June 2010 by Michael Whittaker]

On Bridge Island the chimney which gives it its name still stands, the one break in the monotonous curve of the granite rock forming the island. Concerning the origin of this chimney there exist a number of stories, of which that related by the late John McMullen, a Brockville historian of no mean ability, is probably the most correct. The following is the story as given by McMullen:

In October, 1799, two halfbreed hunters, who spoke little English,made this island their headquarters while hunting along the neighbouring shore, which was at that time almost virgin forest. Apparently finding an abundance of game, they built a small hut on the island and prepared to pass the winter there. As the winter wore on they were joined by a fine-looking French-Canadian of about thirty years of age. "Who he was is not known, but it was evident from the deference and respect the trappers had for him that he was of good birth and influence. He immediately started to build what was in those days a large and magnificent house, cutting down logs on the mainland for the purpose and hauling them across the frozen river.

"When navigation opened in the spring of 1800, lime was brought from Kingston, and a large substantial chimney built, and when all was finished the French-Canadian disappeared as mysteriously as he bad come. About the end of May a large batteau was seen coming down the northern channel, laden with various household articles. Seated in the stern were the Frenchman and a very handsome woman of mixed white and Indian blood, evidently his bride.

The two took up their residence on the island and offered a welcome to all who passed up and down the river. It was plain from the richly cared decorations of the house that the owner was a man of considerable wealth, but except for that there was nothing to reveal his identity. It was thought that he was of Hugenot descent, and that she was the child of one of the mixed marriages that were already beginning to be looked down upon. Tradition varies a great deal here and it is likely that nothing definite will ever be known.

At any rate, farmers from the neighbouring settlements or voyageurs on the river, were alike treated most hospitably and alike departed without knowing who their entertainers were or whence they came.

The fall of that year was unusually dry and on the 25th of October two farmers by the names of Enoch Mallory and Joseph Buck, emerging from the dense woods in which they had been hunting, were surprised to find the island a mass of flames from end to end.

Pushing off in a boat, Mallory and his companion approached the island and waited till they could land. As they rowed around to the little cove at the southern side they were horrified to find a half-burned canoe containing the body of the French-Canadian with a new Indian tomahawk buried deep in the skull. Of the woman or any other soul there was no trace.

News of the tragedy was carried to Brockville, then a small hamlet, and the following day the magistrate, Thomas Sherwood, visited the island in a vain attempt to discover the perpetrators of the crime. Suspicion pointed to the two half-breeds who had disappeared, and when they emerged from the interior, where they had been hunting, they were arrested. However, they were able to clear themselves, although they maintained a mysterious silence regarding the identity of the dead man.

Eventually the story reached Toronto, then Little York, and Major-General Hunter, then Lieutenant-Governor of Upper Canada, directed Peter Cartwright, of Kingston, to make further investigations. His report, which was published in the little Provincial Gazette, revealed nothing that was not already known, and the murder was set down as the revenge of some tribe from whom the Frenchman had abducted his bride.

The chimney now standing on the island is not, however, the one that figures in this little romance, but the ruins of a blockhouse that once frowned over the anchorage formed by the island.

This blockhouse, to which Lieutenant-Colonel W. S. Buell, perhaps the best uulhoi'ily ou the history of these parts, has suggested giving the name of Fort Toniata, to distinguish it from Fort Levis, was erected in 1814 by order of Lieutenant-General G. Drummond. In writing to Sir George Prevost from Kingston, under the date of May 8th, 1814, he says:

"I have found that boats and batteaux Leave frequently been under the necessity of stopping between Brockville and Gananoque on coming up from the Lower Province, a part of the country infested by sw.irins of disaffected people who are constantly in the habit of communicating with the enemy in spite of all our vigilance, and as Bridge Island is situated about fifteen miles from the former and sixteen from the latter place, affords a shelter for boats and an approved site for a work of defense, I have directed Captain Marlow to procure some person willing to undertake the erection of a block- house upon it by contract. The enclosed sketch will give Your Excellency an idea of the place in question."

The blockhouse was evidently built the same summer, for Lieutenant-Colonel Nichols reports in a letter to Sir George Prevost, dated December 31st, 1814, that at Bridge Island he found "The officer commanding endeavouring to put up a miserable picketing in hard frozen ground with a banquette to fire from."

The officer seemed to have been in no way deterred by this, for by scraping the rocks absolutely bare in places he managed to build a very creditable little earthwork at one end of the island to shelter the eighteen-pound carronade and light six-pound field gun. which, with two similar guns in the blockhouse itself formed his defenses. Whether he ever built the abbatis recommended further on in Colonel Nichols's letter, history does not state, and no remnant of any remains. It would have provided amusement for his little force of thirty men of the 57th and five of the artillery.

A short while hater the 70th Regiment station a company there. In that interval, however, miscreants had broken windows and generally played havoc with the place, so the 57th claimed when called upon to explain the damage, and a Sergeant Howlands, assistant barracks master, was sent down to investigate, but the sergeant of the 70th swore the place had sustained no damage since he had taken charge, and there the matter lay, Howlands did not find the island as comfortable as his own fireside in Gananoque evidently, for he reports the place to be untenable during the winter unless repaired, more-over, "The chimneys are the worst I think I ever witnessed. I stayed one night in the place and between the smoke and the cold it was intolerable. The party is badly in need of rugs and palliasses to make them comfortable (at least) at night."

Then he throws out a broad hint that a person in the vicinity would supply wood at 15s a cord.

In his itemized report he gives the blockhouse to be forty-three by twenty-four feet outside, and describes the chimneys as being double and two-storey, in good repair, but smoky', as described. This certainly tallies with the ruins now standing on the island.

Whether the 70th were more careless than the 57th and let the whole place go to ruins is not known. The little discrepancies between the "marching out state" of one regiment and the "marching in state" of another are well known even in these prosaic times.

What eventually became of Fort Toniata is another mystery. Except for the documents quoted the Archives Department apparently contains nothing. Probably the blockhouse having served its purpose and being no longer needed was allowed to fall into ruins, it at last was swept away by fire, as was the former building.

Or possibly, as some think, the conflagration witnessed by Buck and Mallory occurred at a later date than that given by McMullen, and that the building involved was this blockhouse and not the traditional log cabin.

Be that as it may, the tall chimney still stands guard over the mystery of the island, and forms a peaceful home for the shoreline swallows.

The white lake gulls dip and glide and utter their hoarse cries as they swim the placid waters around it.

Redskin and redcoats have long passed away and the poison sumack [sic] alone tosses its scarlet plumes over the barren blistered rock, and from the shelving beach the gentle twitter of the teeter-tail snipe is the only challenge that greets the invader of its silences.

----------------------------

Added to TI Life by Susan W. Smith, Editor, susansmith@thousandislandlife.com