|

The Thousand Islands are the most enduring things on the earth, washed by ever-new currents of water, passing in its eternal cycle from the heavens to the sea and back again. Our islands, some eighteen hundred of them are formed of granite, the oldest material on the face of the planet. Layers of newer rock and soil remain on a few of them, but typically erosion has exposed the summits of ancient mountains, interposed with pockets of thin soil that surprisingly support rich growth of pines and other native flora.

|

Western entrance to the International Rift, Howard Pyle, 1878 (click to magnify)

|

|

Granite and water, Paul Malo photograph.

|

In line with the objective of the Algonquin to Adirondack Conservation Association, UNESCO designated the Frontenac Arch Biosphere Reserve, one of four hundred worldwide. The Biosphere Network provides information about conservation goals in its information center near Ivy Lea and on its website.

The international boundary line could not be drawn down the center of the river, due to large islands. Canada has the larger number of islands, about two thirds. The largest island, Wolfe Island, is Canadian, as is nearby Howe Island, fourth largest. Grindstone and Wellesely Island, second and third in size, are in the United States.

|

Fifty miles of the St. Lawrence River. Map courtesy Ian Coristine / 1000IslandsPhotoArt.com

|

| |

The terrain of the westernmost islands differs from those farther down the river, since from Simcoe to Hickory the islands retain the fairly flat surface seen elsewhere on the lake plain, whereas from Grindstone to Brockville the newer levels of sedimentary rock have disappeared, exposing the more irregular, underlying granite. The Bateau Channel, between Howe Island and the Canadian mainland, follows the line of demarcation, with the City of Kingston lying on the eastern edge of the Frontenac Arch. It is known as "the Limestone City," however, since so many of its historic buildings were built of the sedimentary rock from the lake plain.

| |

Granite, water, and Great Black Gulls (Larus marinus). Ian Coristine / 1000IslandsPhotoArt.com

|

The surface of Wellesley Island is partially covered with more level sandstone, another sedimentary rock, whereas the more northern portion is more rugged because of its exposed granite. The division between the two terrains is the island's interior Lake of the Isles. The changing character of stone is evident where exposed by cuts made for Interstate 81 as it crosses the island.

The historic buildings on Heart Island were constructed of stones from different quarries. Boldt Castle itself employed granite form Oak Island in Chippewa Bay, whereas the Alster Tower appears to be constructed of sandstone, probably from nearby Wellesley Island. Don Ross has written most fully on the geological formation and the natural ecology of the Thousand Islands. Parks Canada has provided some material online.

|

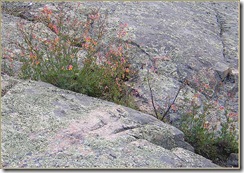

Columbine and Lichen (Aquilegia canadensis and Lichen mosaic). Paul Malo photograph.

|

| |

The islands vary not merely in size and geology, but in the way they are irregularly dispersed, frequently appearing in groups. A British hydrographer who surveyed the river in 1816 recognized and named eight clusters. The Admiralty Group, for instance, contains sixty-four islands near Gananoque. The "Admiralty" term reflects names given islands within the group, memorializing Lords of the Admiralty. Similarly, the named islands of the Navy Group after officers in the Royal Navy, and those of the Lake Fleet after ships of the Royal Navy. The latter are the most colorful, such as "Deathdealer" and "Bloodletter."

Our relatively protected island terrain is habitat to abundant wildlife. The microclimate, tempered by water, supports a distinctive ecology. Nature centers and parks provide programs about our natural environment. Don Ross has written extensively about these matters.

|

Bald Eagles (Haliaeetus leucocephalus) in their Thousand Islands nest, 2004.

Doug Rawlinson, photographer.

|

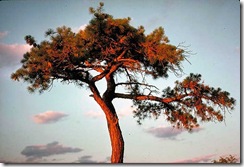

Conservationists observe, "These islands lie in a biological transition zone, between the deciduous and Great Lakes Region forests. Due to the moderating effect of the lake and river, the climate is such that many species reach their northern limit in the Thousand Islands Region. Many islands ... show strong microclimatic effects due to their rugged topography. Southwest slopes are exposed to the sun and have predominant south west winds , and therefore have a hot dry climate typical of much further south. Protected north-east slopes are cool, moist and shady. The vegetation is of a mixed forest type with eastern white and red pines, eastern hemlock and yellow birch. Broad-leaved species such as sugar maple, red maple, red oak and basswood are also found."

<><><> </></></>

|

Old Pitch Pine. Courtesy

|

|

| |

|

Canada Goose (Branta canadensis).Ian Coristine / 1000IslandsPhotoArt.com

|

|

Loon (Common, Gavia immer).

Ian Coristine / 1000IslandsPhotoArt.com

|

The sound of the Loon evokes many memories for those who have lived on islands, hearing the odd cry during quiet nights.

|

|

Double-crested Cormorant.

Photograph copyright Dan Sudia.

|

The St. Lawrence Seaway has altered the ecology of the river. Zebra Mussels, probably introduced from discharge of ocean-going ships' bilge water, have clarified the water, making fish more vulnerable to predatory birds. The Double-Breasted Cormorant has invaded and multiplied rapidly, causing serious concern of fishermen, as well as state and national governments.

|

| Zebra mussels |

|

Zebra Mussels and Catfish ("Bullhead"), Ivy Lea. Jean Langlois Photograph.

|

|

Monarch butterfly (Danaus plexippus) on Turk's Cap Lily (Lilium superbum).

Ian Coristine / 1000IslandsPhotoArt.com

|

|

Gray Tree Frog (Hyla versicolor) going through a metamorphic color change.

|

|

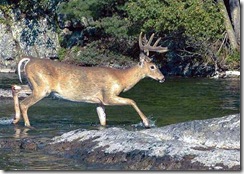

White-tail deer buck.

Photograph courtesy Ontario Parks.

|

|

White-tailed Deer does (Odocoileus virginianus), Hill Island. J. Rawls photograph.

|

|

"Hoover," the Eastern Chipmunk (Tamias striatus), Patty Mondore photograph

|

|

Goose nest.

Ian Coristine / 1000IslandsPhotoArt.com

|

|

An island Mink (Mustela vison).

Ian Coristine / 1000IslandsPhotoArt.com

|

|

Canadian Porcupine (Erethizon dorsatum).

Randy Caccia photograph.

|

|

Great Blue Heron.

John Schuck photograph

|

|